Lendel Narine, University of Florida, lendel.narine@ufl.edu

Amy Harder, University of Florida, amharder@ufl.edu

Priscilla Zelaya, P4H Global, priscilla@p4hglobal.org

Abstract

The Cooperative Extension Service faced many challenges and threats over its history. Persistent internal challenges affecting Extension are communication with stakeholders, high employee turnover, and a marketing deficit. Common external threats included reduced funding, increases in non-traditional audiences, and inadequate facilities. Guided by a needs assessment framework, this study sought to identify the challenges and threats facing the [State] Cooperative Extension Service at the county level. Using a basic qualitative research design, the final reports from the 2016 county program reviews were used as the primary source of data. Results were consistent with the literature and showed persistent challenges facing Extension were staff limitations, marketing and communication ineffectiveness, limited program coverage, inadequate volunteer recruitment, and lack of funding. Threats found were unresponsiveness to changing audiences and inadequate facilities. It is recommended that Extension’s strategic plan focus on priority areas while emphasizing the urgency needed to close identified gaps in marketing and communication, staff development and retention, and program quality, delivery, and coverage. Steps are needed to improve its performance by efficiently allocating resources to serve a diverse clientele, strengthen agents’ programmatic areas, and build strong partnerships with relevant organizations.

Introduction

Cooperative Extension faces many internal challenges in planning and delivering educational programs to diverse audiences (Harder, Lamm, & Strong, 2009). Some of these challenges are its inability to maintain a contemporary image to stakeholders, and a high rate of employee burnout leading to high turnover. Major external threats arise due to reduced funding due to increased competition and shrinking budgetary allocations through the Federal formula funding model (Harder et al., 2009). There are several grand challenges at the national level Extension must overcome to meet its overriding mission of providing research-based solutions to local communities (Henning, Buchholz, Steele, & Ramaswamy, 2014). Henning et al. discussed the need for Extension to find innovative approaches to addressing issues of climate change, diminishing natural resources, and evolving food safety practices. In addition, Henning et al. highlighted the increased expectations of a rapidly growing urban clientele and changing population demographic for Extension to tailor its programs to serve non-traditional audiences. Such challenges demand a philosophical shift in Extension programming, and require greater emphasis on community partnerships, adoption and command of innovative technologies, and appropriate professional development programs targeted at agents and volunteers.

While grand challenges are looming over Extension’s future success and relevance, there are internal challenges and external threats to Extension at the county level. These include county-level challenges such as Extension’s antiquated image among stakeholders; a high rate of employee turnover, stress and frustration, and; difficulties in overcoming many barriers to technology adoption (Harder et al., 2009). The Extension Committee on Organization and Policy (ECOP) identified agent retention as a major challenge to Extension (Safrit & Owen, 2010). Financial challenges in Extension resulted in greater workload for employees, which led to greater employee stress and burnout (Feldhues & Tanner, 2017). As a result, Feldhues and Tanner found staff turnover increased as per capita funding decreased. Further, agents’ inability to recognize and manage volunteers was related to being overburdened with other tasks (McCall & Culp, 2013). High employee turnover coupled with challenges in attracting volunteers negatively impacts the quality and quantity of programming efforts.

External threats to county-level Extension in Florida were funding reductions, an increase in non-traditional audiences and the lack of programming to meet such audiences, and insufficient facilities such as office space (Harder et al., 2009). Extension clients from Florida were mostly white, non-Hispanic, and had at least some college education (Galindo-Gonzalez & Israel, 2010). Still, Hoag (2005) indicated Extension’s survival depended on its ability to reach new audiences and address evolving societal problems. With threats to funding, and the need to increase program coverage among a changing clientele, Extension is “being pressured to do more with less” (Ahmed & Morse, 2010, p. 1).

Major challenges and threats to Extension were revealed in county reviews during 2008 to 2010. Extension faced challenges related to a marketing deficit and technology barriers in county reviews of 2008, 2009, and 2010 (Mazurkewicz & Harder, 2011). This points to a deficiency in Extension’s ability to communicate value to all stakeholders, and a lack of command of modern technologies to improve Extension programming. As such, there is a need for Extension to provide “systematic and convincing evidence of program value” (Stup, 2003, p. 1). The public value of Extension must be communicated effectively to stakeholders to ensure continued funding from public sources (Baughman, Boyd, & Franz, 2012; Franz, Arnold, & Baughman, 2014). Another challenge prevalent in 2009 and 2010 was the lack of program coverage for non-traditional audiences and lack of a representative advisory council. In addition, Mazurkewicz and Harder (2011) noted consistent threats during the same period were the downturn of the economy, changing demographics, and inadequate facilities.

Noticeably, challenges and threats identified by Mazurkewicz and Harder (2011) at the county level directly relate to the grand challenges facing Cooperative Extension at a national level as discussed by Henning et al. (2014). County-level reviews are an important evaluation tool in assessing Extension’s efforts and capacity to serve clientele. Interventions at the county level are needed to drive efforts needed to addressing grand challenges faced by Extension. However, literature on challenges and threats to county-level Extension is limited and, in most cases, outdated. This study provides a timely assessment of challenges and threats facing Extension. It allows some insight into county-level needs and serves as a basis for designing interventions to improve county-level programming. A needs assessment can reveal the challenges and threats affecting Extension’s performance and provide a basis to identify opportunities to improve Extension. Therefore, this study uses a needs assessment framework to examine the challenges and threats to county-level Extension programming in Florida.

Theoretical Framework

Extension must seek to accomplish its aims and objectives with limited financial and non-financial resources. Budgetary allocations are distributed to specific programs, activities, and tasks according to performance objectives. Performance-based budget allocations in Extension are stipulated through the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 and the Agricultural Research, Extension, and Education Reform Act (AREERA) of 1998 (Ladewig, 1999). According to Witkin and Altschuld (1995), a needs assessment is the most effective way to decide on resource allocation in organizational planning. A need is a discrepancy between an actual state (what is) and a desired state (what should be) (Witkin & Altschuld, 1995). The actual state is defined as the present output or current progress of an organization. For example, the actual state of Extension in any given year might be described in terms of clientele’s satisfaction with Extension programs, program coverage in urban areas, and number of programs facilitated by an agent. In contrast, the desired state is often expressed as pre-defined organizational objectives, such as the mission and corresponding priorities of Extension. Therefore, a need is the difference between current and desired results (Kaufman, 1988).

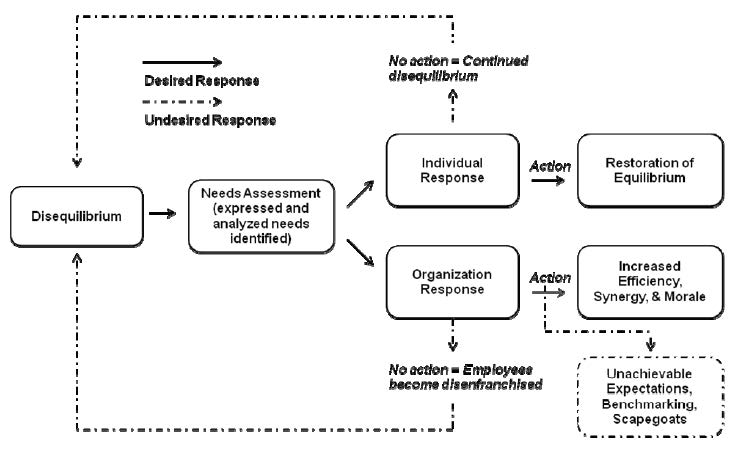

Boyle (1981) described the presence of a need as tension causing a disequilibrium in Lewin’s (1951) field theory of motivation. Disequilibrium results in an urge to return to an otherwise natural state of equilibrium (Weiner, 1972). Individuals take steps to close the gap between current and desired states, thereby satisfying the need. Extension is expected to utilize resources to minimize or eliminate discrepancies between the actual and desired state of performance. Therefore, a needs assessment is “a systematic set of priorities undertaken for the purpose of setting priorities and making decisions about program or organizational improvement and allocation of resources” (Witkin & Altschuld, 1995, p. 4). From Figure 1, a needs assessment identifies the disequilibrium within an organization. Action is taken at the individual and organization level to restore equilibrium. A failure to respond at both levels leads to continued disequilibrium and can manifest as undesirable outcomes such as unachievable expectations. Action taken based on the needs assessment allows a return to equilibrium.

Figure 1. A needs resolution process. From “An Analysis of the Priority Needs of Cooperative Extension at the County Level,” by Harder et al. (2009), Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(3), p. 13. Reprinted with permission.

Continuous monitoring is necessary to identify organizational needs (Boyle, 1981). The University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) county program review is a formative evaluation conducted annually with the aim of improving program delivery (Jacob, Israel, & Summerhill, 1998). The review considers program quality and delivery and incorporates an examination of administrative performance. The review results guide strategic planning of extension programming (Jacob et al., 1998). As a formative evaluation, the review aims to improve Extension services by identifying needs and providing feedback using a SWOT analysis approach (McLean, 2006). Therefore, needs identified are categorized as challenges or threats; challenges are internal factors and threats are external factors. Utilizing a county program review process will provide Extension administrators with information on county-level needs and may offer solutions to these problems to improve the quality of Extension programming according to the overall mission of UF/IFAS Extension.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to assess gaps within county-level Extension and identify opportunities for improving the quality of Extension programming at the county level for UF/IFAS Extension. The objectives were to assess the needs of Extension at a county level and categorize these needs into internal challenges and external threats that were or had the potential to negatively impact Extension programming.

Methods/Procedures

A basic qualitative research design (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) was used for this study. The basic qualitative design is commonly used in education research to examine recurring patterns and themes emerging from participant data. The primary goal is to describe and interpret participants’ experiences with a phenomenon (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The study was determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board. The final written reports from county program reviews conducted in 2016 (N = 5) were used as the primary sources of data. The reports were each developed by separate four-person review teams, consisting of one county agent, one District Extension Director, one Extension program leader, and one state Extension specialist, all of whom were employed by UF/IFAS Extension. County staff, agents, stakeholders, and county government officials were interviewed over two or three days, depending upon the size of the county. Information gathered during the interviews, as well as background information about the county Extension provided to the review team prior to the review, was used by the review teams to describe in the reports what they observed to be strengths, challenges, opportunities, and threats associated with the programming offered by a county Extension office.

Five counties were purposively selected to undergo county reviews in Florida. One county within each of the five Extension districts was selected by the District Extension Director to participate in the country program reviews of 2016. The five counties selected in 2016 employed between two and five agents. The smallest county had a population of 27,360 while the largest county housed a population of 315,187 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014). Selected counties were predominantly white, ranging from 69.4% to 90.8%. Considerable variance was observed for the percentages of people reporting Hispanic ethnicity (4.2% – 43.4%). The most common racial minority was black or African American, ranging from 6.1% to 23.0%. Per capita income ranged from $17,179 to $31,141. Extension programs offered to the residents of the reviewed counties commonly included 4-H, agriculture, horticulture, and family and consumer sciences, but there were also natural resources programs and sea grant programs in some counties.

The data was categorically divided by the researchers using constant comparative analysis (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). This method entails comparing notes on an incident with another incident in the same data set. Eventually, constant comparisons between different interview notes lead to tentative categories or themes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). One section of data was carefully compared with other sections in order to identify any recurring themes and sub-themes related to challenges and threats impacting Extension programming. An internal debriefing was conducted following the initial analysis to discuss the findings and develop the final interpretation of the data (Anzul, Ely, Freidman, Garner, & McCormack-Steinmetz, 2003).

Ensuring the trustworthiness of the data was of concern. Member checking was conducted in accordance with recommendations made by Lincoln and Guba (1985); the review teams provided an initial oral report of their findings to each county office at the end of each review. Any clarification needed from the county level was obtained at that time. Further, the written reports were examined for accuracy by each county’s Extension director as well as the Senior Associate Dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Multiple investigators served on each review team and independently contributed to the development of the reports, resulting in what Merriam and Tisdell (2016) described as “investigator [sic] triangulation” (p. 245). The data itself reflected information from a variety of interviewed sources during the review, as explained earlier.

Reporting the potential for researcher bias is important when discussing trustworthiness (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). One member of our team, Harder, has extensive experience with UF/IFAS Extension, particularly with directing the county program reviews. She has directed the county program reviews since 2008. Prior to her experience with UF/IFAS Extension, Harder was a 4-H agent in Colorado, an experience that has shaped her professional perspective. The potential for Harder’s past experiences to influence the analysis of the data used for this study existed, therefore the initial data analysis was conducted by a second team member, Zelaya, with familiarity with the reviews in her role as a graduate assistant working for UF/IFAS Extension but without the same degree of engagement. The third researcher, Narine, contributed a solid foundation in program development and evaluation but had no prior experience with UF/IFAS Extension to potentially bias his interpretations.

As a qualitative study, this research is not intended to be generalized beyond the five counties that were reviewed. However, thick description (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) was used when describing the counties and county offices reviewed to aid the reader in determining transferability to other Extension settings. Similarly, the integration of quotes in the findings helps the reader to understand the context.

Results/Findings

The following challenges and threats were identified from the five county program review reports. Coding was used when including direct quotes from the reports.

Challenges

Staff limitations impact programming. Challenges associated with staffing limitations were present in all county program reviews. Most challenges related to staffing presented in the county reviews were due to limited agent positions in specific program areas. In one report, the removal of a staff position led to “a large nursery industry presence in the county [being] underserved” (R1). One county was without a Horticulture Agent, which led to difficulties when “the office receives a large number of homeowner horticulture questions” (R3). Difficulties also arose by having a County Extension Director (CED) “spread over multiple counties” (R4) which made it “difficult to do much work within the assigned program area.” Increased amounts of walk-in clientele created a “time management issue” (R4) within one county; the report cited the need to include the administrative assistant in resolving this particular difficulty. Additionally, support staff in one county desired to have more responsibility but were “underutilized” (R4).

Volunteer practices. The county program reviews revealed a gap in volunteer communication and recruiting practices. Volunteers in one county were trained by multiple agents in the past, leading to inconsistent volunteer practices (R1). New policies recently introduced into 4-H led to a need for agents to educate “the volunteers about the positive benefits of the new 4-H membership fee” (R1). Educating volunteers on the new membership fee was a challenge faced by two counties within the county program reviews (R1, R3). The recruitment of volunteers was also an identified challenge within some reports; one report recommended agents “recruit volunteers within other Extension program areas beyond 4-H” (R4). Additionally, another county report identified potential volunteers in the county’s growing elderly population (R5).

Policies regarding facility use were also seen as challenges when working with volunteers. The county operating policies in one county required that “a staff member must be present when a volunteer is using the office after hours” (R4). In order to comply with the policy, staff members had to be present in the office after hours. The review report suggested “volunteers be strongly encouraged in this instance to find alternate meeting locations for volunteer coordinated evening programs” (R4).

Lack of adequate resources. Throughout the county program reviews, the lack of resources was seen as a challenge facing every county. The resources cited within the reviews included funding, facilities, and transportation. As programs develop and expand within counties, funding becomes a challenge (R1, R3, R4). In one county, funding was needed to expand the reach of program marketing (R1). In another county, funding was needed to “identify a solution to the new photo ID requirements for volunteer background” (R3). One county report identified a need to find funding for a program that had “0% county funding support” (R5). While programming needs were a concern for county staff, “funding for professional development travel and professional association membership” (R1) were perceived as barriers to early career growth in faculty (R1, R5).

Physical resources were also lacking. Lack of space for storage and future growth (R2, R3), unreliable Internet bandwidth (R1), and aging infrastructure of facilities (R1) were among the challenges cited by reviewers. Concern was also expressed about the public’s perception that the distance of the county office location was not convenient (R5).

Difficulties in external and internal communication. Communication practices with stakeholders outside the county offices were sources of challenges cited within county reviews. Reviewers cited a need to increase “public relations and marketing efforts” (R2) in order to reach more clientele and diverse audiences in one county. Marketing efforts mentioned within the county reviews included updating the “website by linking partnerships, adding newsletters” (R3) and other articles to improve resource availability for the community. The need for developing consistent strategies was expressed by one county (R5). Challenges in marketing efforts also included the need to “disseminate information to clientele” (R1). In one county, concerns over the “time it takes to develop marketing plans, implement, and evaluate them” (R5) impacted current marketing strategies. Throughout the county reviews, the communication practices utilized externally were a central focus.

While external communication practices were central to the county program reviews, internal communication practices were also cited as challenges within counties in this study. Agents in one county failed to share “program minutes for each advisory group” (R3) with the County Extension Director and “Overall Advisory minutes” (R3) with the District Extension Director. In a second county, the communication path between county government and the Extension office was regularly disregarded (R4). Finally, the internal and external communication practices in a third county were “impacting the morale of faculty, staff, and volunteers” (R5).

Threats

Environmental concerns. Local environmental issues are current threats for counties in this study. The presence of citrus greening has “put many farms in crisis mode” (R1) and the possibility of the crisis extending into the surrounding communities has caused concern. Additionally, the “high probability of urban expansion over the long-term” (R1) was also cited as a potential threat to county programming; the county for which this was reported is one of Florida’s historically productive agricultural areas. The threat of extreme weather was a concern for one county (R5) due to the “distractions” they cause in “the delivery of educational programs.”

Specific programming needs. Subsets of the populations reached by county offices are increasing and are creating needs for future programming. In one county, “about 90% of call-ins are hobby farmers” (R4). Despite the growing number of hobby farmers in that county, county program reviewers did not report specific programming aimed at the hobby farmer population. Additionally, the number of small niche farmers was increasing in the same county and questions about how this population was being served emerged (R4). Concern also existed over the “perceived duplication of services by other county units and agencies” (R5).

Potential staff attrition. Staff attrition was a cited concern for two counties (R1, R3) within this study. “Future career possibilities of early-career faculty” (R3) were identified as possible threats to the cohesive continuation of future programming.

Conclusions/Recommendations/Implications

Results of the 2016 annual county review indicated several persistent problems, many of which were consistent to those discussed by Feldhues and Tanner (2017), Galindo-Gonzalez and Israel (2010), Harder et al. (2009), Henning et al. (2014), Mazurkewicz and Harder (2011), and Safrit and Owen (2010). Challenges such as staff limitations, marketing and communication ineffectiveness, program coverage, volunteer recruitment, and lack of funding were present in previously conducted reviews in Florida. Similarly, identified threats from 2016 replicated findings from previous year’s reviews including unresponsiveness to changing audiences and inadequate facilities.

The results highlighted some growing areas of concern, pointing to several operational deficiencies in Extension. A lack of agents in program areas such as horticulture had a negative impact on program coverage and volume of clientele served. Further, administrative inefficiencies existed due to limited support staff. The challenge of limited support staff was exacerbated by problems encountered in training volunteers, coupled with the low number of volunteers. Based on the results, there is a need to hire administrative staff, hire program staff, and improve volunteer management at the county level. A lack of response may result in continued disequilibrium in the counties examined, negatively impacting performance (Boyle, 1981). The needs assessment provides a rationale to allocate resources according to organizational priorities (Witkin & Altschuld, 1995).

The reduction in funding has been a persistent theme in the county program reviews. Consistent reduction in funding hinders Extension’s ability to hire new staff in important program areas, which leads to increased workloads of employees (Feldhues & Tanner, 2017). In turn, employees are stressed, which negatively impacts staff retention rates. Further, an increased workload can lead to employee burnout. These factors may affect the quality of Extension programming and limit the ability of agents to expand programming to reach new audiences, such as non-traditional clientele. Funding constraints directly affects program coverage (Ahmed & Morse, 2010). New funding models (e.g. funding arrangements with municipalities, increased program fees, or more grant-funded projects) and/or alternative staffing models (e.g. increasing the number of project-based, time-limited positions versus permanent-status track positions) should be explored to determine their potential to increase Extension’s financial resources. At the local level, agents need to be empowered (and willing) to let go of programs and activities that cannot be sustained when positions go unfilled.

Another key challenge was deficiencies in internal and external communications. Extension’s inability to communicate the value of Extension to its stakeholders was identified as a persistent issue plaguing Extension and is consistent with the literature (Baughman, Boyd, & Franz, 2012; Franz, Arnold, & Baughman, 2014; Mazurkewicz & Harder, 2011). However, results also indicated there was also ineffectiveness of the communication channels between CEDs and advisory groups. According to Elving (2005), ineffective communication channels can result in a slower response and adaptation to internal and external changes in the environment. This may limit Extension’s capacity to meet stakeholders’ evolving needs. There is a need to improve internal communication channels to ensure effective and efficient communication between CEDs and advisory groups. UF/IFAS Extension needs to provide professional development for CEDs on how to effectively work with advisory groups; however, the state specialist position that previously provided this type of expertise is currently vacant and it is unknown if or when it will be filled. CEDs will need to look for external training in order to develop this skillset, possibly through their professional associations.

With respect to threats, issues identified by Henning et al. (2014) such as extreme weather, changing demographics, and urbanization were present in the review reports. However, a specific threat identified was the duplication of services, creating the potential for inefficiencies in the allocation of Extension resources. Program activities should be assessed against program priorities to ensure effective programming coverage. This requires greater coordination of efforts at a local and regional level to ensure fewer redundancies in program planning. This will allow resources to be allocated in a way that best supports Extension’s ability to be uniquely impactful in each county.

Serious issues affecting the effectiveness and efficiency of Extension at the county level were identified as a result of the county program reviews. These findings indicate the importance of continuous monitoring through periodic needs assessments and other formative evaluation tools (Boyle, 1981). UF/IFAS Extension’s strategic plan should focus on priority areas while emphasizing the urgency needed to close identified gaps in marketing and communication; staff development and retention; and program quality, delivery, and coverage. Even in an era of decreased funding, Extension must take the necessary steps to improve its performance by efficiently allocating resources to serve a diverse clientele, strengthen agents’ programmatic areas, and building partnerships with relevant organizations.

References

Ahmed, A., & Morse, G. W. (2010). Opportunities and threats created by Extension field staff specialization. Journal of Extension, 48(1). Retrieved from https://www.joe.org/joe/2010february/rb3.php

Anzul, M., Ely, M., Freidman, T., Garner, D., & McCormack-Steinmetz, A. (2003). Doing qualitative research: Circles within circles. London: Routledge.

Baughman, S., Boyd, H., & Franz, N. (2012). Non-formal educator use of evaluation results. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(3), p. 329-336. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.11.008

Boyle. P. G. (1981). Planning better programs. USA: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Elving, W. J. L. (2005). The role of communication in organizational change. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 10(2), 129-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280510596943

Feldhues, K., & Tanner, T. (2017). Show me the money: Impact of county funding on retention rates for extension educators. Journal of Extension, 55(2). Retrieved from https://www.joe.org/joe/2017april/rb3.php

Franz, N., Arnold, M., & Baughman, S. (2014). The role of evaluation in determining the public value of Extension. Journal of Extension, 52(4). Retrieved from https://www.joe.org/joe/2014august/comm3.php

Galindo-Gonzalez, S., & Israel, G. D. (2010). The influence of type of contact with Extension on client satisfaction. Journal of Extension, 48(1). Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/2010february/a4.php

Harder, A., Lamm, A., & Strong, R. (2009). An analysis of the priority needs of Cooperative Extension at the county level. Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(3), 11-21. doi: 10.5032/jae.2009.03011

Henning, J., Buchholz, D., Steele, D., & Ramaswamy, S. (2014). Milestones and the future for Cooperative Extension. Journal of Extension, 52(6). Retrieved from https://www.joe.org/joe/2014december/comm1.php

Hoag, D. L. (2005). Economic principles for saving the Cooperative Extension Service. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 30(3):397-410. Retrieved from http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/30982/files/30030397.pdf

Jacob, S., Israel, G., & Summerhill, W. (1998). [State] Cooperative Extension’s county program review process. Journal of Extension, 36(4). Retrieved from http://www.joe.org/joe/1998august/a5.php

Kaufman, R. (1988). Planned educational systems: A results-based approach. Lancaster, PA: Technomic.

Ladewig, H. (1999). Accountability and the Cooperative Extension System. Unpublished paper presented at the Cooperative Extension Program Leadership Conference. Pittsburgh, PA.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. New York: Harper.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mazurkewicz, M., & Harder, A. (2011, February). A longitudinal study of challenges and threats from county extension program reviews [Abstract]. Proceedings of the Southern Region Conference of the American Association for Agricultural Education, 61, 543-547.

McCall, F. K., & Culp, K. (2013). Utilizing a state level volunteer recognition program at the county level. Journal of Extension, 51(6). Retrieved from https://joe.org/joe/2013december/iw5.php.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Safrit, R. D., & Owen, M. B. (2010). A conceptual model for retaining county Extension program professionals. Journal of Extension, 48(2). Retrieved from https://joe.org/joe/2010april/a2.php

Stup, R. (2003). Program evaluation: Use it to demonstrate value to potential clients. Journal of Extension, 41(4). Retrieved from https://www.joe.org/joe/2003august/comm1.php

U. S. Census Bureau. (2014). State and county QuickFacts. Retrieved from www.quickfacts.census.gov

Weiner, B. (1972). Theories of motivation: From mechanism to cognition. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Witkin, B. R., & Altschuld, J. W. (1995). Planning and conducting needs assessments: A practical guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.