Katherine Bezner, Oklahoma State University, kbezner@okstate.edu

Audrey E. H. King, Oklahoma State University, audrey.king@okstate.edu

Lauren Lewis Cline, Oklahoma State University, lauren.l.cline@okstate.edu

Bree Elliott, Oklahoma State University, bree.elliott@okstate.edu

Kane Kinion, The Ohio State University, charles.k.kinion@okstate.edu

Abstract

First-year college students are entering higher education with less agricultural knowledge overall, leading to misperceptions about potential career paths associated with their chosen degree programs. Researchers in Oklahoma State University’s Agricultural Education, Communications and Leadership (AECL) Department’s pilot undergraduate research course desired to explore students’ perceptions of the department’s majors and internal brand. A quantitative, exploratory survey was completed by 207 students. Students felt most knowledgeable about their chosen major, were satisfied with their major choice, and anticipated obtaining a job upon graduation based on their major. When social pressures and career readiness perceptions of the majors were analyzed according to major program, most students showed a preference for their own major among the indicators. However, results varied on the students’ perceptions of other majors within the department. Agricultural communications was perceived the most positively by all AECL majors. Agricultural leadership was considered to be the most inclusive. Agricultural education was perceived to be the most important major program to the agricultural industry. It is recommended the AECL Department implement a multidisciplinary freshman orientation program, conduct a communications and branding assessment for recruitment and retention, and explore qualitatively the meaning of student perceptions of majors.

Introduction

Changing demographics among colleges of agriculture nationwide call for diverse degree options available to students (Foreman et al., 2018). First-year college students are also entering higher education with less agricultural knowledge overall (Colbath & Morrish, 2010), leading to misperceptions about potential career paths associated with their chosen degree programs. The attributes of academic programs are communicated by faculty and staff (Erdoğmuş & Ergun, 2016). Studies show factors such as potential financial earnings and social standing influence students’ perceptions of majors rather than the content and focus of the discipline itself (Fosnacht & Calderone, 2017). Simultaneously, the average job tenure across the U.S. is less than five years (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). Perhaps the misconceptions regarding agriculture and its related majors, combined with the influential factors on major choice, have created a disconnect between major choice satisfaction and job tenure lengths for college of agriculture graduates (Scofield, 1994).

Agricultural education departments serve an essential role in preparing a skilled and proficient workforce (McKim et al., 2017). Moreover, it is important agricultural education departments, or programs encompass a variety of agricultural social sciences (Barrick, 1989). To achieve these goals, the Agricultural Education, Communications and Leadership (AECL) Department at Oklahoma State University (OSU) must understand the perceptions of its undergraduate students toward the departmental majors. This understanding could offer insights about the internal brand and culture of the department as a whole.

Researchers in the AECL Department’s pilot undergraduate research course desired to explore students’ perceptions of the department’s majors and internal brand. These students felt a disconnect between the three programs. The interdisciplinary research team developed this study to examine organizational silos within the department. The internal brand of the AECL Department was explored by surveying other undergraduate students.

Literature Review

As the interest in student retention has increased, research regarding student major satisfaction and undergraduate students’ perceptions has also increased. Student major satisfaction, which is influenced by internal branding, is a crucial component to a student’s academic success (Milsom & Coughlin, 2017). Moreover, major satisfaction is one of the largest factors impacting undergraduate student retention (Graunke &Woosley, 2005). Numerous studies have found students are influenced to choose majors with high job availability and high financial return (often referred to as career readiness indicators) after graduation (Del Rossi & Hersch, 2008; Baker et al., 2013). Moreover, recruitment materials for academic majors that demonstrate high job stability are most appealing to prospective students (Baker et al., 2011).

Other fields have studied the challenges that face departments when several majors are housed in one department. For example, bioinformatics majors face considerable challenges when integrating their major program into life sciences departments. Institutional support issues have been reported as a plausible cause for this department divide (Bianchi et al., 2019).

Institutional support issues are described as a lack of internal faculty support for a given major program (Bianchi et al., 2019). If a disconnect arises within a group, an organizational silo can form, impairing a department’s overall functionality (Evans, 2012). Evans (2012) described the reality of organizational silos by stating:

Silos segregate one type of grain from another and the segregated parts within an organization. In a business suffering from silo syndrome, each department or function interacts primarily within that silo rather than with other groups across the organization. (p. 176)

External branding efforts can bring awareness to available major programs; however, a student’s autonomy and connection to an academic department can be more meaningful (Joseph et al., 2012). Research indicates a student’s major choice can be impacted by the academic environment’s friendliness and atmosphere (Stair et al., 2016). Additionally, faculty can either perpetuate or address misconceptions related to college majors and can even influence a student’s major choice (Alam et al., 2019; Hertel & Dings, 2014). Research concerning student perceptions is commonly reported; however, there is a lack of research focused on undergraduate students’ perceptions of other major programs within an academic department. Staff and faculty opinions may contribute to students’ perceptions of not only their major but other programs as well (Hertel & Dings, 2014). Within academic departments, these interpersonal relationships between students and faculty can be challenging to cultivate. This can be influenced by departmental siloing, or the act of not crossing disciplines when conducting research, classwork, or other forms of learning (Guth, 2017). Therefore, by exploring an academic department’s brand value, one could better identify student perceptions and instill a proactive approach to prevent organizational siloing and promote learning (Friedman & Kass-Shraibman, 2017).

Theoretical Framework

Branding is not only a theory, but a practice that attempts to distinguish a product, corporation, or organization from others (Franzen & Moriarty, 2009). A brand is not a logo or tagline. A brand is created through a system of exchanges between brand managers and consumers, known as the receiver of branding messages. In this study, the brand manager is operationalized as the department as a whole, and students would be considered to be the brand consumers. It is impossible to understand a brand as independent from the environment in which it exists (Franzen & Moriarty, 2009). Moreover, a brand exists for an organization regardless of the intentional creation of the organization. Though abstract, a strong brand is invaluable in today’s marketplace (Swaminathan et al., 2020).

A critical aspect of branding efforts is creating a strong internal brand (Punjaisri & Wilson, 2011; Sartain & Schumann, 2006). An internal brand is displayed through the way the internal stakeholders display the brand to external audiences. Internal brands are particularly important for service-based organizations that depend on interactions between people to thrive (Schmidt & Baugmgarth, 2018). Internal branding can be promoted through relationships and peer-to-peer interactions. Studies have shown that teaching staff and attitude towards the university are major factors in student success and satisfaction within their major (Erdoğmuş & Ergun, 2016).

The framework for this study integrated internal branding and student perceptions. It was adapted from Punjaisri and Wilson’s 2011 work that described internal branding communication, including brand identification, brand commitment, and brand loyalty. The level at which these three components operate is known as an organization’s brand performance (Punjaisri & Wilson, 2011). When consumers and stakeholders identify with the brand, they consider themselves part of the brand itself (Punjaisri & Wilson, 2011). Brand commitment is the psychological connection between a brand or service and the stakeholder (Punjaisri & Wilson, 2011). Brand loyalty is the continued service and investment in a certain product or organization (Punjaisri & Wilson, 2011).

Recently, higher education branding has become a more researched phenomena (Chapleo, 2011; Dholakia, 2017). Universities, like corporate entities, work to distinguish themselves from the competition. However, universities are more complex than corporations, and therefore, so is their Branding (Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002). A strong university brand helps students navigate the decision of picking the university that is right for them by displaying the differences between schools and displaying the unique attributes of a university (Chen & Chen, 2014). Researchers agree that students’ educational experience is of the utmost importance in an overall university brand (Ng & Forbes, 2009; Pinar et al., 2014). Many factors, including departmental structure, faculty, staff, and peers, can be affected by a student’s educational experience and university brand.

The general atmosphere of the university also affects brand loyalty (Erdoğmuş & Ergun, 2016). A study has shown students value a sense of community not only within their department but also in their university as a whole (Erdoğmuş & Ergun, 2016). The same study also showed that fellow students’ opinions did not impact their educational choices. However, it is important for current and incoming students to have a positive relationship with program alumni, as their opinions and experiences are influential when students make educational decisions (Erdoğmuş & Ergun, 2016).

When studying students’ perceptions of brand equity (i.e., the value of a brand), researchers found the most important factors are the perceived quality of faculty, university reputation, brand loyalty, academic offerings, prestige, career readiness, and emotional environment. These factors are intertwined and ultimately build university brand awareness (Alam et al., 2019; Pinar et al., 2014). Similar to the emotional environment finding of Pinar et al. (2014), Eldegwy et al. (2018) found students who were satisfied with the social aspects of the university were more likely to recognize, recommend, and pay for the university brand.

Perceived quality of education, the institution’s social image, and job market success were important factors for university selection among students in the U.S. (Mourad et al., 2020). Studies have shown that faculty bring their brand to their classrooms. However, internal branding is related to the orientation of faculty behavior, which ultimately results in the student’s experience (Sujchaphon et al., 2015). Thus, for universities to deliver on their brand promise, it is important for faculty to properly communicate that brand (Sujchaphon et al., 2015).

University branding is a priority for undergraduate recruitment. The end goal for university first-year student success should be a long-term student retention rate (Cox & Naylor, 2018). A student’s feeling of self-efficacy influences retention. A sense of belonging can be heightened with involvement in an orientation program (Huddleston, 2000). Orientations are commonly used to communicate the culture and brand of an organization. Therefore, multidisciplinary classrooms with small and large group activities can serve as an innovative model to encourage peer-to-peer discussions and diversity of education (Stebleton et al., 2010). A collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to recruitment can serve as a vehicle for brand identification and brand loyalty.

Departmental Background

The OSU agricultural education program (EDUC) was established in the early 1920s (Oklahoma State University, personal communication, 2014). The department expanded to add an agricultural communications program (COMM) was added shortly after. As interest in the department continued to grow, the agricultural leadership program (LEAD) was approved in 2005 (Oklahoma State University, personal communication, 2005).

OSU has an undergraduate student retention rate of 83.2% (Oklahoma State University, 2014). The department has incorporated multiple strategies to retain students: one-on-one academic advising with faculty, developing major career paths, and academic support. These types of strategies increase the strength of the department’s internal brand. A strong internal brand can help to retain and attract students (Devasagayam et al. 2010). The strength of an internal brand is demonstrated through student or employee behaviors and their relation to organizational values (Simi & Sudhahar, 2019). A strong internal brand can result in increased student involvement in department clubs, professional organizations, and extracurricular activities. Organizations that are collaborative and demonstrate a unified internal brand are more appealing (Alshathry et al., 2017).

For the purpose of this study, the university brand is described as how external stakeholders view the organization, which includes students, parents, and mentors. Internal branding consists of the internal stakeholders, faculty, and staff, who have an inside viewpoint of the brand. We are going to frame this study to explore internal departmental branding, which we have operationalized to mean undergraduate students in the AECL Department at OSU and their perceptions of the department brand.

Research Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to describe the undergraduate AECL Department students’ perceptions of the AECL Department undergraduate majors at OSU. Three research questions guided this study:

- What perceptions do AECL Department students have about their majors?

- What perceptions do AECL Department students have about other majors in the department?

Methods

This study was conducted as a quantitative, exploratory survey using a 10-item researcher-developed questionnaire. The study was conducted at OSU among a convenience sample of undergraduate students in the AECL Department. Of the 389 enrolled undergraduate students in the department at the time, 208 completed the questionnaire, but one incomplete questionnaire was removed from the study. The final response rate was 53.2% (N = 207). AECL undergraduate students identified their major as agricultural education (EDUC; n = 66, 31.9%), agricultural communications (COMM; n = 98, 47.4%) and agricultural leadership (LEAD; n = 35, 16.9%). Eight students identified as one of several double-major options in the department; it is noted that these students were included in analysis of demographic data to describe participants to determine a representative sample, but not included in further analysis based on the research questions and low response rates per double-major option.

Demographic data were collected from the study’s participants (N = 207). Participants were classified academically as freshmen (n = 7, 3.4%), sophomores (n = 43, 20.8%), juniors (n = 74, 35.7%), and seniors (n = 82, 39.6%). Participants included 161 (77.8%) self-identified females and 46 (22.2%) self-identified males. Of this population, about 62% (n = 129) entered OSU as first-semester freshman, about 37% (n= 77) were transfer students, and less than one percent (n = 1) entered as an exchange student. More than three-quarters (n = 163, 78.7%) reported their hometown as a rural, agriculturally based community. Thirty-eight participants (18.4%) reported their hometown as urban/suburban. The distribution of participants across the undergraduate majors in the AECL Department was deemed to be representative of the overall population.

The questionnaire consisted of 10 items based on the literature review related to student major choice, career readiness indicators, and internal branding. The first item analyzed for this study explored the influence of social pressures (e.g., other people’s opinions, family pressure, prestige, and career readiness indicators) to AECL Department students’ choice of major. The remaining nine questions gathered demographic data.

To establish reliability, the questionnaire was piloted among a 15-person AECL Department graduate research methods course. The instrument demonstrated acceptable test- retest reliability with Phi correlation coefficients ranging between .51 and .90. Minor edits were made to items with poor reliability and an advisory group of three AECL Department faculty representing the three undergraduate majors to ensure the face and content validity of the final questionnaire. The finalized questionnaire was distributed during a one-week period of the fall semester among 20 departmental courses. Data were analyzed using SPSS© Version 23.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were calculated to answer the research questions.

Results

Research Question 1: What perceptions do AECL Department students have about their majors?

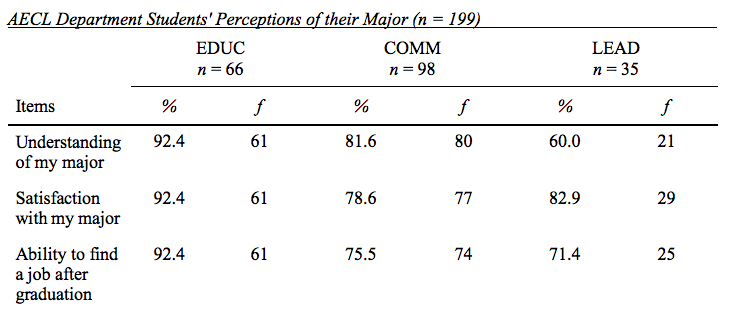

Analysis of the items related to the perceptions undergraduate AECL Department students had about their major program demonstrated students were most knowledgeable about their chosen major. As shown in Table 1, most EDUC and COMM students believed they understood their major, while fewer LEAD students felt the same. More than 70% of students in all three majors appeared to be satisfied with their major.

Table 1

Research Question 2: What perceptions do AECL Department students have about other majors in the department?

To address the second research question, students were given a set of career readiness indicators and asked to choose the major they believed provided the best opportunity for each indicator. The six indicators and student responses aggregated by major and total responses are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1

When looking at the perceptions of EDUC students (n = 66) across the six indicators of career readiness, EDUC students preferred their major among three out of six indicators. EDUC students considered the EDUC major to be the most inclusive (n = 31, 47%) and provided the most job opportunities (n = 42, 63.6%). Of the remaining three indicators, EDUC students believed the COMM major had more high-quality careers (n = 35, 53%), the highest potential income earning opportunity (n = 38, 57.6%), and was the most progressive and forward thinking (n = 23, 34.8%).

COMM students (n = 98) preferred their major among five of the six indicators. COMM students believed the COMM major to be the most inclusive (n = 56, 57.1%), provided more job opportunities (n = 66, 67.3%;), a higher-quality career (n = 87, 88.8%;), and had the highest potential income-earning opportunity (n = 70, 71.4%). COMM students believed the EDUC major was the most important to the agricultural industry (n = 65, 66.3%).

LEAD students (n = 35) preferred their major among three of the six indicators. LEAD students believed the LEAD major provided more job opportunities (n = 18, 51.4%), was the most inclusive (n = 28, 80%), and was the most progressive and forward-thinking (n= 24, 68.6%). Of the remaining three indicators, LEAD students perceived the COMM major as providing more high-quality careers (n =18, 51.4%) and the major with the highest potential income-earning opportunity (n = 15, 42.9%). LEAD students believed the EDUC major was the most important to the agricultural industry (n = 23, 65.7%).

When looking at the overall data, a consensus was shown by students from the three majors among three of the career readiness indicators. When data were aggregated, students believed the EDUC major was the most important to the agricultural industry (n = 147, 73.8%). The LEAD major was believed by more than one-third of the students to be the most inclusive program (n = 72, 36.2%). The COMM major was believed to provide more job opportunities (n = 98, 49.2%), more high-quality careers (n = 140, 70.4%), the highest potential income earning opportunity (n = 123, 61.8%), and to be the most progressive and forward thinking (n = 94, 47.2%).

Conclusions and Implications

Participants in the study were more likely to report their background as rural and agriculturally based than urban, which is representative of college of agriculture demographics at other institutions (Foreman, et al., 2018). More than three-quarters of students’ hometowns were a rural, ag-based community. Therefore, it could be concluded the prevalence of rural students might impact the internal branding of the AECL Department, as there may be a significant difference in major choice and perceptions between students with rural/ag-based backgrounds and urban/suburban students. Participants in this study were also primarily female, similar to the student population’s overall demographics within the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Iowa State University (Foreman, et al., 2018). The ratio of enrollment for male and female participants in our study was also consistent with the changing demographics of other colleges of agriculture in the United States (Foreman, et al., 2018). Perhaps the department’s recruitment efforts are over-investing in rural, ag based communities. The AECL Department’s internal brand influences undergraduate students and their perceptions of majors within the department. To increase collaboration, a multidisciplinary orientation course can enhance peer-to-peer discussions and diversity of education (Stebleton et al., 2010).

Research Question 1: What perceptions do AECL Department students have about their majors?

Findings indicated most AECL Department students felt they were knowledgeable, satisfied, and able to obtain a job after graduation with their major program. These positive preferences correlate to strong major satisfaction and internal branding buy-in. It seems natural for students to be most knowledgeable about their own majors. Strong major satisfaction is related to higher GPA levels, and it should be noted that students interested in multiple major programs do not necessarily improve their academic standing (Milsom & Coughlin, 2017). A student’s sense of belonging can be most influenced by interaction with faculty and staff members (Alam et al., 2019). Similarly, faculty members can contribute to student perceptions of other majors in an academic department (Hertel & Dings, 2014). Our college requires faculty academic advising, and most departmental faculty have a majority teaching appointment.

Participants in our study have the most exposure to their major program’s peers and faculty, which may have also impacted their perceptions of the department’s internal brand.

Research Question 2: What perceptions do AECL Department students have about other majors in the department?

Overall, COMM was perceived the most positively by all AECL Department majors. COMM was consistently identified as a major with career opportunities and benefits for graduates. EDUC was portrayed as the most important major to the agricultural industry. LEAD was considered to be the most inclusive. It is worth noting the COMM major was the most represented in our sample for this study. When perceptions of the majors were analyzed by their major program, most students showed a preference for their own major among the indicators. However, results varied on the students’ perceptions of other majors within the department. As a result, COMM student responses may have skewed the distribution of aggregated data for most items. This insight draws attention to the fact that LEAD was considered to be the most inclusive major despite students in each major perceiving their own major to be the most inclusive. Perhaps there were more defectors, or less consensus, within the majors for that particular item. Our findings could translate to a possible organizational silo within the AECL Department based on students’ tendency to prefer their own major among the items. Students enrolled in majors without multidisciplinary crossover may be in a less functional learning environment operating as an organizational silo (Friedman & Kass-Shraibman, 2017).

Recommendations

The findings demonstrate theoretical implications for student major selection. Based on the congruency between the findings in this study and the literature review, these are the following recommendations for the AECL Department: (a) implementation of a multidisciplinary freshman orientation program; (b) a recruitment assessment for retention; and (c) a qualitative study examining the meaning of student perceptions of majors.

A multidisciplinary freshman orientation course should be implemented to increase collaboration within the AECL Department and reduce a perceived organizational silo. This course would be a collaboration between faculty and graduate students in the department. At OSU, other programs have implemented orientation courses including animal science, agricultural economics, and a basic orientation course for all freshmen enrolled in the college of agriculture. Other disciplines have successfully implemented multidisciplinary courses, which increased the confidence level of major choice among their undergraduate students (Copp et al., 2012).

A multifaceted communications approach focused on the department’s internal brand is needed for the success of both student recruitment and student retention rates. The internal branding of a department is most effective when all programs work cohesively (Alshathry, 2017). The buy-in for internal branding among potential and current students positively correlates to personal meetings (Devasagayam, 2010). High-achieving students are not influenced by campus visits alone; therefore, we suggest that faculty continue to hold personal meetings face-to-face with prospective students and academic advising meetings with current students. Additionally, departmental branding and communications should be evaluated for cohesiveness and inclusive representation of each major program across recruitment materials and publications.

To improve organizational siloing within the department, the lack of understanding between the three major programs needs to be addressed. Perhaps a disconnect in the internal branding of the department has created misconceptions between students. A more collaborative departmental environment could increase student buy-in and academic success (Schreiner, 2009). As student buy-in rises, the department will have less student turnover and major changes.

Perhaps a qualitative study could explain the meanings of AECL Department student perceptions toward other majors in the department. An additional exploratory study would be beneficial to interview students and gauge from their responses how they perceive the internal Branding of the AECL Department. These conclusions could be used to further strengthen the internal brand of the AECL Department and improve both faculty and student brand loyalty.

Future research should also be conducted on the number of AECL Department students who work in the agricultural industry after graduation. This study was focused more on the quantity of student responses, whereas future studies could look to see if different perceptions of majors exist based on a variety of student demographic variables.

Our research had several limitations, one being that career readiness and programmatic statements were based on our (the research team’s) perceptions of the department majors. The internal brand of a department may not be viewed the same by each of its constituents. Another limitation of this study was the inability to generalize and apply the results to other departments and institutions. It would be beneficial to replicate this study within the social sciences departments of other colleges of agriculture. The instrument needs to be validated among multiple settings with the target population for continued research use.

Although our research focused on students within the AECL Department at OSU, this study may serve as a guide to gain a better understanding of the agricultural education discipline as a whole. More research needs to be conducted on student major choice and satisfaction in the social science field of agriculture. Future studies should include students who change their major and leave the department. It is evident AECL Department students communicate and perceive majors, and levels of career readiness within those majors, differently; this can be a limitation for students if they have misconceptions about the career readiness and opportunities of a major.

References

Alam, M. I., Faruq, M. O., Alam, M. Z., & Gani, M. O. (2019). Branding initiatives in higher educational institutions: Current issues and research agenda. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 1, 34-45. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2019.1-03

Alshathry, S., Clarke, M., & Goodman, S. (2017). The role of employer brand equity in employee attraction and retention: A unified framework. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(3), 413-431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2016-1025

Baker, L., Settle, Q., Chiarelli, C., & Irani, T. (2013). Recruiting strategically: Increasing enrollment in academic programs of agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(3), 54-66. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2013.03054

Baker, L. M., & Abrams, K. (2011). Communicating strategically with generation me: Aligning students’ career needs with communication about academic programs and available careers. NACTA Journals, 55(2), 32-39. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/1148/Baker_JUNE%202011%20NACTN%20Journal-8.pdf

Barrick, K. (1989). Agriculture education: Building upon our roots. Journal of Agricultural Education, 30(4), 24-29. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1989.04024

Bianchi, C., Williams, J. J., Drew, J. C., Galindo-Gonzalez, S., Robic, S., Dinsdale, E., Morgan, W. R., Triplett, E. W., Burnette, J. M., Donovan, S. S., Fowlks, E. R., Goodman, A. L., Grandgenett, N. F., Goller, C. C., Hauser, C., Jungck, J. R., Newman, J. D., Pearson, W. R., Ryder, E. F., Sierk, M., Smith, T. M., Tosado-Acevedo, R., Tapprich, W., Tobin, T. C., Toro-Martínez, A., Welch, L. R., Wilson, M. A., Ebenbach, D., McWilliams, M., Rosenwald, A. G., & Pauley, M. A. (2019). Barriers to integration of bioinformatics into undergraduate life sciences education: A national study of U.S. life sciences faculty uncover significant barriers to integrating bioinformatics into undergraduate instruction. Plos One, 14(11), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224288

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Employee Tenure in 2020. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/tenure.pdf

Chapleo, C. (2011). Exploring rationales for branding a university: Should we be seeking to measure branding in the U.K. universities? Journal of Brand Management, 18(6), 411-422. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2010.53

Chen, C.-F., & Chen, C.-T. (2014). The effect of higher education brand images on satisfaction and lifetime value from students’ viewpoints. Anthropologist, 17(1), 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2014.11891423

Colbath, S. A., & Morrish, D. G. (2010). What do college freshman know about agriculture: An evaluation of agricultural literacy. NACTA Journal, 54(3), 14-17. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/414/Colbath_September_2010_NACTN_JOURNAL-5.pdf

Copp, N. H., Black, K., & Gould, S. (2012). Accelerated integrated science sequence: An interdisciplinary introductory course for science majors. Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education, 11(1), A76-A81. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3592751/

Cox, S., & Naylor, R. (2018). Intra-university partnerships improve student success in a first- year success and retention outreach initiative. Student Success, 9(3), 51-64. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v9i3.467

Del Rossi, A. F., & Hersch, J. (2008). Double your major, double your return? Economics of Education Review, 27(4), 375-386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.03.001

Devasagayam, R. P., Buff, C. L., Aurand, T. W., & Judson, K. M. (2010). Building brand community membership within organizations: A viable internal branding alternative? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19(3), 210-217. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421011046184

Dholakia, R. R. (2017). Internal stakeholders’ claims on branding a state university. Services Marketing Quarterly, 38(4), 226-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332969.2017.1363580

Eldegwy, A., Elsharnouby, T. H., & Kortam, W. (2018). How sociable is your university brand? An empirical investigation of university social augmenters’ brand equity. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(5), 912-930. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2017-0346

Erdoğmuş, İ., & Ergun, S. (2016). Understanding university brand loyalty: The mediating role of attitudes towards the department and university. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 229, 141-150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.07.123

Evans, N. (2012). Destroying collaboration and knowledge sharing in the workplace: A reverse brainstorming approach. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 10(2), 175-187. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2011.43

Foreman, B., Retallick, M., & Smalley, S. (2018). Changing demographics in college of agriculture and life sciences student. NACTA Journal, 62(2), 161-167. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/2730/12%20Beth%20Foreman.pdf

Fosnacht, K., & Calderone, S. M. (2017). Undergraduate financial stress, financial self-efficacy, and major choice: A multi-institutional study. Journal of Financial Therapy, 8(1), 107-123. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1129

Franzen, G., & Moriarty, S.E. (2009). The Science and Art of Branding (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315699042

Friedman, H. H., & Kass-Shraibman, F. (2017). What it takes to be a superior college president: Transform your institution into a learning organization. The Learning Organization, 24(5), 286-297. https://doi.org/10.1108/tlo-12-2016-0098

Graunke, S., & Woosley, S. (2005). An exploration of the factors that affect the academic success of college sophomores. College Student Journal, 39(2), 367-376. https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA133606107&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&llinkacces=abs&issn=01463934&p=AONE&sw=w

Guth, D. J. (2017). Building a new structure. Community College Journal, 87(5), 28-33. https://eric.ed.gov/?q=guth+2017+building+a+new+structure&id=EJ1142040

Hertel, T. J., & Dings, A. (2014). The undergraduate Spanish major curriculum: Realities and faculty perceptions. Foreign Language Annals, 47(3), 546-568. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12099

Huddleston, T. J. (2000). Enrollment management. New Directions for Higher Education, 111(7), 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.11107

Joseph, M., Mullen, E. W., & Spake, D. (2012). University branding: Understanding students’ choice of an educational institution. Journal of Brand Management, 20(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2012.13

Mazzarol, T., & Soutar, G. N. (2002). “Push‐pull” factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82-90. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540210418403

McKim, A. J., Greenhaw, L., Jagger, C., Redwine, T., & McCubbins, O. P. (2017). Emerging opportunities for interdisciplinary application of experiential learning among colleges and teachers of agriculture. NACTA Journal, 61(4), 310-316. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/2669/McKim_EmergingOpportunities.pdf

Milsom, A., & Coughlin, J. (2017). Examining person-environment fit and academic major satisfaction. Journal of College Counseling, 20(3), 250-262. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocc.12073

Mourad, M., Meshreki, H., & Sarofim, S. (2020). Brand equity in higher education: Comparative analysis. Studies in Higher Education, 45(1), 209-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582012

Ng, I. C. L., & Forbes, J. (2009). Education as service: The understanding of university experience through the service logic. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 38-64. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841240902904703

Pinar, M., Trapp, P., Girard, T., & Boyt, T. E. (2014). University brand equity: An empirical investigation of its dimensions. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(6), 616-634. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijem-04-2013-0051

Punjaisri, K., & Wilson, A. (2011). Internal branding process: Key mechanisms, outcomes and moderating factors. European Journal of Marketing, 45(9/10), 1521-1537. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111151871

Sartain, L., & Schumann, M. (2006). Brand from the inside. Jossey-Bass.

Schmidt, H. J., & Baumgarth, C. (2018). Strengthening internal brand equity with brand ambassador programs: development and testing of a success factor model. Journal of Brand Management, 25(3), 250-265. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0101-9

Schreiner, L. A. (2009). Linking student satisfaction and retention. Noel-Levitz.

Scofield, G. G. (1994). An Iowa study: Factors affecting agriculture students career choice.

NACTA Journal, 38(4), 28-30. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/754/Scofield_NACTA_Journal_Dec_1919-7.pdf

Simi, J., & Sudhahar, C. (2019). Dimensions of internal Branding: A conceptual study. Journal of Management, 6(1), 177-185. https://doi.org/10.34218/jom.6.1.2019.019

Stair, K., Danjean, S., Blackburn, J. J., & Bunch, J. C. (2016). A major decision: Identifying factors that influence agriculture students’ choice of academic major. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 4(2), 111-125. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304494995_A_Major_Decision_Identifying_Factors_that_InfluencI_Agriculture_Students’_Choice_of_Academic_Major

Stebleton, M. J., Huesman, R. L. J., & Kuzhabekova, A. (2010). Do I belong here? Exploring immigrant college student responses on the SERU survey sense of belonging/satisfaction factor. Center for Studies in Higher Education Research & Occasional Paper Series, 13(10), 1-12. https://cshe.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/publications/rops.stebleton_et_al.immigrantstudents.9.14.10.pdf

Sujchaphong, N., Nguyen, B., & Melewar, T. (2015). Internal branding in universities and the lessons learnt from the past: The significance of employee brand support and transformational leadership. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 204-237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2015.1040104

Swaminathan, V., Sorescu, A., Steenkamp, J.-B. E. M., O’Guinn, T. C. G., & Schmitt, B. (2020). Branding in a hyperconnected world: Refocusing theories and rethinking boundaries. Journal of Marketing, 84(2), 24-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242919899905