Chris Clemons, Auburn University, cac0132@auburn.edu

Jason D. McKibben, Auburn University, jdm0184@auburn.edu

Clare E. Hancock, Auburn University, cet0071@auburn.edu

James R. Lindner, Auburn University, jrl0039@auburn.edu

Abstract

This qualitative study investigated instructional practices SBAE teachers use in their lessons to develop knowledge and understanding of content and disciplinary words, terms, and phrases. The overarching question guiding this research study addressed what pedagogical practices SBAE teachers incorporate within their lessons for developing disciplinary literacy. The theoretical basis for this study was structured using Bandura’s model of triadic reciprocal causation (1997). Three research questions guided this study: 1) What methods of instruction did secondary SBAE teachers use to develop agricultural literacy in SBAE students? 2) What assessments did secondary SBAE teachers use to measure if students are developing literacy skills in agricultural education? 3) How did secondary SBAE teachers incorporate agricultural literacy into agricultural students’ development? The participants consisted of practicing secondary school agriscience teachers in Alabama. The data yielded four primary themes organized into four sections. The findings of this study indicated that SBAE teachers used explicit explanations to bring new concepts and vocabulary to students, motivated their learning through group work, and led them in project-based activities to apply new ideas in real-life situations. SBAE teachers were helping students gain agricultural knowledge, which is foundational to agricultural literacy. Teachers expressed frustration with administrative oversight on literacy instruction and developing speaking, listening, and writing skills. Teachers reported that vocabulary was a mandated component of the agriscience curriculum. However, their instruction needs to include writing exercises to improve student literacy in agricultural education. Recommendations for further study indicate that teachers build on their present writing activities, add extended individual writing to the learning process, and consolidate new vocabulary knowledge by applying new terms and concepts by writing to synthesize ideas and concepts. It is also recommended that SBAE teachers work collaboratively with their administration to develop a deeper understanding of the best practices and proven methods for improving literacy skills in agriculture.

Introduction

Articulating the knowledge and understanding of agriculture requires the teaching and furtherance of reading, writing, and communicating using specialized words and terms. This tenet has been the cornerstone of agricultural education since the passage of the Morrill Act of 1862 and the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917. Hasselquist et al. (2019) stated: “Disciplinary literacy includes the way the content is organized, how it communicates key information, technical vocabulary, and how texts are used.” (p. 141). Understanding pedagogical practices for developing disciplinary knowledge and improving reading, writing, and communication in agriculture is vital for student learning. Instructional literacy practices in school-based agricultural education (SBAE) classrooms enable students to master the distinction between being disciplinary literate and possessing knowledge and understanding in agriscience education. Shanahan and Shanahan (2012) characterized disciplinary literacy as speaking, listening, and writing using specialized words and terms. Therefore, all SBAE teachers are responsible for instructing, developing, and promoting literacy (Park & Osborne, 2007), often through agricultural contexts. According to Lemley, 2019, the expectation exists in SBAE to support agricultural education students to meet the shifting expectations of the 21st-century workforce. This study addressed teachers’ understanding of integrating writing into instructional activities to affect student literacy.

The Smith-Hughes Act (C.F.R., 1960) addressed the improvement of agricultural practices without explicitly mentioning literacy: “The preparation of those preparing to enter upon the work of the farm or of the farm home” (p. 107). The insinuation of this passage suggests that improving agricultural practices would require those individuals engaged in the profession to possess literacy to advance knowledge. This passage is narrowly descriptive of today’s expectations associated with agricultural education. However, the foresight for improving instructional literacy methods in the 21st century remains just as profound. The historical foundations of knowledge and understanding in agricultural education are replete with the importance and value of literacy. Roberts and Ball (2009) supported a society of agriculturally literate citizens and the dualistic role of SBAE, the development of a skilled workforce, and literate contributors to society. Blythe et al. (2015) reported that today’s society requires scientifically literate citizens, and developing an agreed-upon definition of agriculturally literate students was supported by Hess and Trexler (2011). Clemons et al. (2018) highlighted that limited studies since the early 1990s have attempted to close the distance between being literate in agriculture and agricultural literacy.

The value of a content literate populace or students endeavoring to become disciplinarily literate was described in Wallace’s Farmer Weekly Journal (1908) as cited by Cremin (1967), “It is hard for many a middle-aged farmer to get a clear idea of what is meant by protein, carbohydrate, nitrogen-free extract, etc.” (p. 45). The proceeding statement implies the importance of words, terms, and phrases for citizens to become disciplinarily literate. To address the gap between being literate and possessing literacy, a distinction between the terms should be addressed: “Agricultural literacy differs from agricultural education in that its focus is on educating students about the field of agriscience rather than preparing students for work within the field of agriscience” (Vallera & Bodzin, 2016, pp. 102–103). The gap between knowledge and understanding of agriculture and agricultural literacy accentuates the importance of literacy education in SBAE classrooms. Developing student literacy prevents them from falling behind in SBAE classrooms and their future employment (Hasselquist et al., 2019).

The development of agricultural literacy has been fostered over 125 years through curriculum development and has shaped the role of SBAE. In Wallace’s Farmer Weekly Journal (1908), the connection between well-trained agriculturalists possessing knowledge and understanding and developing literacy begins with SBAE students. Agriculture education teachers experience a variety of student learning deficiencies in reading, writing, and communicating agricultural words and terms. Hasselquist et al. (2019) reported the challenges SBAE teachers experience when introducing instructional literacy strategies in classroom lessons. The challenges stem from SBAE teachers’ belief that literacy instruction is supplemental to the content area, teacher attitudes towards literacy instruction are fostered from personal experiences and literacy skills should be taught outside their classroom (Hasselquist et al., 2019). Hasselquist et al. (2019) supported Clemons et al. (2018) findings that agricultural professionals have specific feelings and thoughts about the profession. Park and Osborne (2007) found that only 14 percent of SBAE teachers promoted reading strategies for SBAE students in SBAE classrooms. Tummons et al. (2020) reported that literacy skills and techniques are vital for SBAE teachers, although acquiring instructional skills is not always taught in teacher education programs. When accounting for student learning difficulties in literacy, SBAE teachers do not see themselves as English teachers (Park et al., (2010). Essential reading, writing, and communication skills are necessary to acquire knowledge and may allow an understanding of agriculture concepts. This skill gap can be difficult for some students to overcome.

Shoulders and Myers (2013) reported that teaching agricultural literacy often relies on using multiple pedagogical styles to provide students with a foundation for learning. Traditional learning environments rely heavily on teacher-centered dissemination (Alston & English, 2007). Various learning models structure the acquisition of disciplinary knowledge and understanding in the 21st-century agriscience classroom. Kolb’s (2012) experiential learning theory, project-based learning (Smith & Rayfield, 2016), and social development theory (Vygotsky, 1978) are widely used to frame teaching literacy in SBAE classrooms. McKim et al. (2017) referred to the value of instructional methods, knowledge, and problem-solving as pedagogy, or a “Common [set] of competencies that include motivating students to learn, managing behavior, teaching students with special needs, and using technology as a teaching tool.” (p. 3). Instructional methods provide for contextual hands-on learning in agricultural education. However, reading, writing, and communication development using skills acquired through knowledge and understanding is often not emphasized during instruction. Understanding the methods SBAE teachers use to improve student literacy may further the research conducted by Tummons et al. (2020) regarding how practitioners and researchers consider new teaching and learning strategies for pre-service and practicing SBAE teachers.

Theoretical Framework

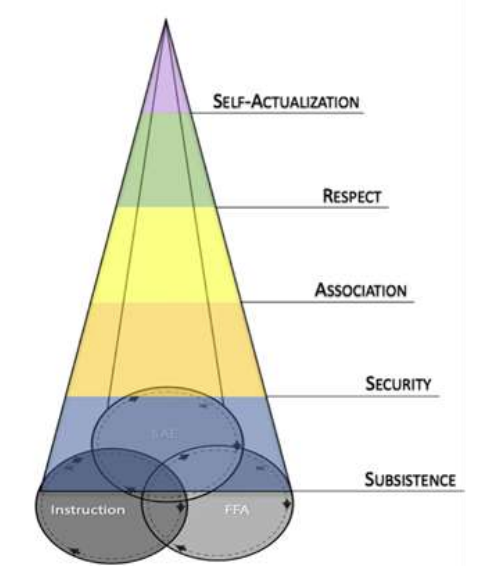

The theoretical basis for this study was structured using Bandura’s model of triadic reciprocal causation (1997). Bandura (1997) theorized that the interconnectivity between the person (P), environment (E), and behavior (B) affects the desired change and postulated reciprocity between the person (P), the environment (E), and behavior (B). Vygotsky (1978) believed that for learning to occur, the “Student will be interacting with people in their environment and cooperating with their peers” (p. 90).

Bandura (1997) reported personal (P) factors as “the beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (p. 3). This assumption provided the basis for examining teacher-initiated literacy instruction in secondary school agriscience education. Bandura (1997) described the environment (E) as a pathway for influencing self-efficacy by using models to impact student learning (Bandura, 1997; Roberts et al., 2008). When students learn within the classroom environment, self-efficacy can be validated through comparative methods of individual performance when measured against their peers. Self-efficacy of the individual (teacher) “refers to the beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce the given attainments” (Bandura, 1997, p. 3).

Roberts et al. (2008) reported that self-efficacy is specialized, where a person can possess high efficacy in one area and diminished efficacy in others. Fuhrman and Rubenstein (2017) wrote that a teacher’s ethos of education occurs through “interactions between the individual, behavior, and the environment.” (p. 225). Shunck (2004) citing Rosenthal and Zimmerman (1978), reported that skills to foster declarative, procedural, and conditional literacy instruction for students are dependent on performance and observation, reinforcing the person (P) and the environment (E) to affect behavior (B). Balancing the need for positive self-efficacy and improving student outcomes is challenging (McKibben et al., 2022). For example, high self-efficacy in content instruction may result in low self-efficacy when SBAE teachers apply literacy instruction in the agriscience classroom.

Purpose and Research Questions

This study aimed to investigate the pedagogical practices secondary SBAE teachers incorporated within their lessons for developing knowledge, understanding, and improvement of agriculturally literate students. Three research questions guided this investigation: (1) What methods of instruction did secondary SBAE teachers use to develop agricultural literacy in SBAE students? (2) What assessments did secondary SBAE teachers use to measure if students are developing literacy skills in agricultural education? (3) How did secondary SBAE teachers incorporate agricultural literacy into agricultural students’ development?

Methods

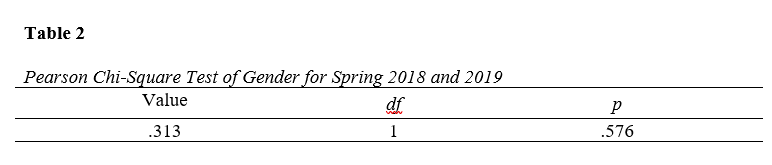

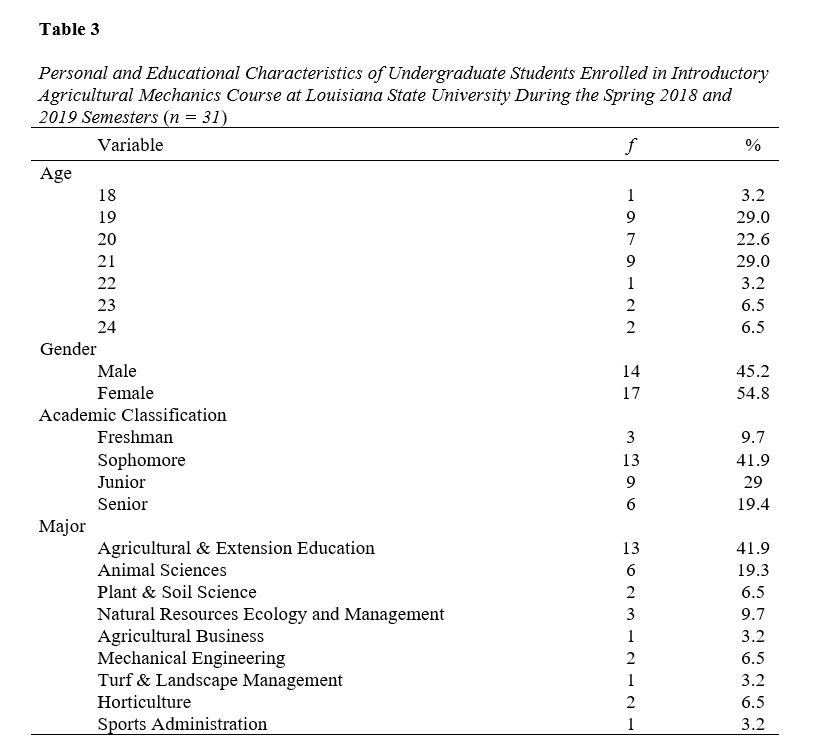

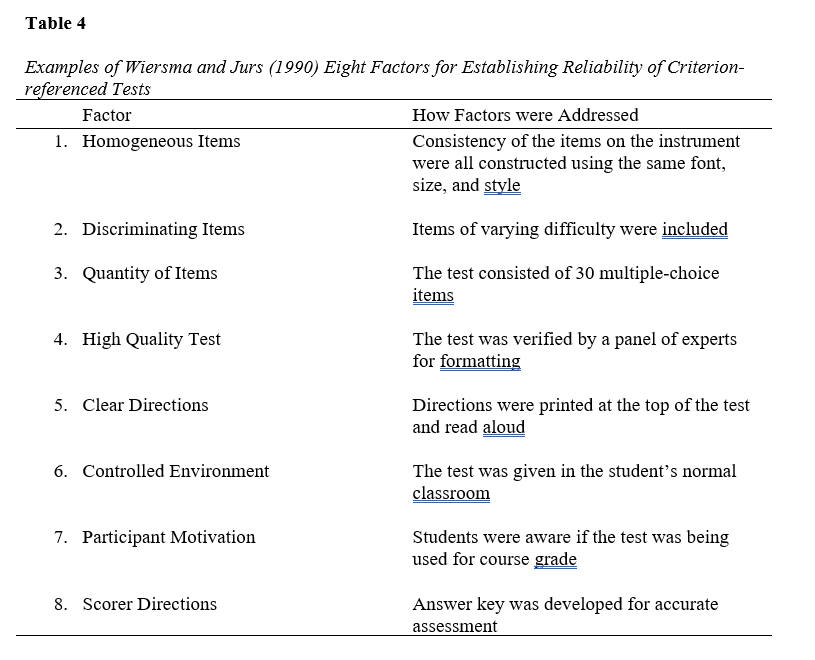

We developed a one-day professional development session addressing agricultural literacy to aid teachers’ understanding of the differences between agricultural literacy and being agriculturally literate. The ten participants indicated their interest in the professional development workshop during the Alabama Association of Agricultural Educators conference. SBAE teachers attended the professional development because they were interested in literacy education and developing literate students in SBAE coursework. After the professional development session, the same ten secondary SBAE teachers agreed to participate in the study, and interviews were scheduled after the professional development session. Telephone interviews were conducted within three weeks of the professional development meeting, with each interview lasting 40 minutes. Interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

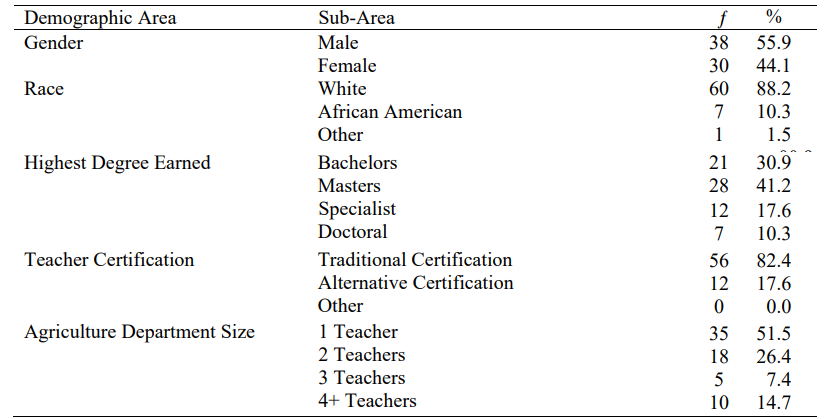

The participants comprised four women (40.0%) and six men (60.0%). Following qualitative design measures for anonymity (Kaiser, 2009), teachers self-selected pseudonyms to protect their identities and responses: Aloe Vera, Big Country, Hank, Jane, Ken Powers, Lee, Mini Mouse, Otis, Pike Place, and Winnie. The small sample size of this study is supported by existing research (Young &Casey, 2018; Hennick et al., 2016), where small sample sizes in qualitative research can represent the full experiences of the participants. Delbecq et al. (1975) also supported the use of ten to fifteen subjects in qualitative research when the backgrounds of the participants are homogenous. Three structured interview questions were posed to each participant with follow-up questions based on responses used to collect data: a) What methods of instruction do you most commonly use to develop knowledge and understanding of SBAE students? b) What types of assessments do you use to measure if students possess literacy or are literate in the discipline? and c) Where do you believe knowledge, understanding, and being disciplinary literate should be introduced in lesson design and delivery? The structured response questions were prepared before the interviews based on previous literacy research and the stated theoretical framework (Merriam, 2009). Audio file interviews from each participant were captured digitally.

Data were transcribed, coded, organized by findings, and arranged using theme development. Open coding, a component of qualitative data analysis, uses the constant comparative method to discover consistent themes within the data. Open coding allows researchers to identify the participants’ thoughts, ideas, and concepts to drive the thematic development process instead of predetermined thematic concepts (Merriam, 2009). Independent analysis of participant comments was evaluated and organized using each of the three research questions and follow-up questions to the participants by the researchers. Trustworthiness of the collected data was ensured as this study’s participants possessed differentiated educational backgrounds, years of experience in education, age, and professional accomplishments. The analysis identified four primary thematic categories for organizing participant responses. Transcendental analysis provided the means for determining the essence of secondary SBAE teacher literacy instruction to develop students’ ability to be literate in agriscience (Brown et al., 2015). These processes identified data for creating themes, interpretations, and a detailed description of the instructional process. After independent coding, we used peer discussions to improve credibility (Guba & Lincoln, 1989) and establish sub-themes to better organize responses to the research questions.

Findings

Data analysis identified four primary thematic categories: 1) classroom environment (teacher controlled), the instructional methods used for the daily instruction of goals and objectives. This was the environment in which teachers set the expectations and instructional delivery models for teaching and learning; 2) the learning environment (student-controlled) reflected the skills, aptitudes, and potential gaps in knowledge and skills students demonstrate during instruction. This environment can reflect prior education, familial expectations, limitations, or the geographical location of the school and community; 3) foundational competencies (skills/materials) refer to the instructional materials that reinforce instructional lessons, including textbooks, technical manuals, news articles, and periodicals; and 4) limitations (administration) describes the policies for student learning determined outside of the teachers’ classroom or sphere of influence. These policies may include mandated assessments, administrator-determined vocabulary, or time devoted to specific instruction techniques. Subsequent analysis identified sub-themes within each thematic category.

Classroom Environment (Teacher Controlled)

The teachers reported variations in class schedules: 40.0% indicated a traditional 60/40 class period day, 50.0% taught within a four-by-four block schedule, and 10.0% experienced an eight-block class schedule. The analysis of the collected data yielded three sub-themes: instructional choice, pedagogy (methods and practices of teaching), and learning assessment.

Instructional Choice

The different methods and practices for teaching words, terms, and phrases were centered on traditional instruction (direct instruction, vocabulary identification) practices in the classroom. Participants explained that their instructional methods would depend on the content of the course. Hank explained his process for determining appropriate teaching methods for literacy instruction, “The methods of instruction would depend on the class. . . animal science class would be a lot more terminology than basic agriscience or introduction to agriscience.” Hank emphasized terminology through practical hands-on applications: “I do a lot of reading for content using engine manuals or other technical-based texts. Then, we [class] discuss terms like an air gap, oil type, and preventative maintenance. I think that’s where our focus is when reading for information.” Hank’s instruction reflected instructional choices steeped in content and disciplinary word association, reinforcement, and application.

Big Country expressed similar traditional instruction methods when determining delivery for improving knowledge and understanding. Big Country emphasized formal instruction, “I use a lot of PowerPoint materials, and students take notes from the screen.” Other participants indicated that their instructional methods were similar to their own educational experiences in high school when learning words, terms, and phrases. Hank conveyed his experiences as a veteran teacher in the secondary agriscience classroom. He stated: “In my first year of teaching, I was giving notes, lectures, PowerPoint presentations, diagrams, etc., and realized this is not what kids want . . . they want to rip their hair out.” Lee supported Hank’s first-year experiences instructing students using words, terms, and phrases and how he approached teaching content to his classes. Lee said: “I’d go around the room, and one student would read a section, and I would offer feedback and then have classroom discussion on the material being read. That’s how I taught all the students in each class.” Otis remembered being a high school sophomore and enrolling in SBAE classes. His memory provided a historical context regarding literacy instruction, which translated to his instructional style during his first two years of teaching agriscience education. Otis reflected:

I remember copying notes in high school I didn’t understand because I was more concerned with the process of taking notes from the board than what I was supposed to be learning. I was concentrating on transcribing the information instead of learning the information.

Hank reinforced high school experiences in literacy education and discussed his memories of engaging teachers and the methods they used to teach reading and writing skills. He indicated, “I had some great teachers as a high school student. My English teacher was very engaging during reading and discussion as a class. I try to mimic his methods when I teach my students.”

Pedagogy: Methods and Practices of Teaching

Each participant explained the various methods and strategies for delivering instruction, and a common theme emerged among the teachers. Delivery methods for instructional purposes included guided notes, contextual learning, scaffolding instruction, and prior educational experiences. For example, using guided notes in the classroom allowed students to direct their attention to the lesson instead of the note-taking process. Lee noted: “One thing I do is have my notes printed off, and then I provide them [notes] to the students.” Lee supported using guided notes when asked to elaborate on his experiences. He said, “I’m not your science or history teacher putting notes on the board for you [students] to copy.” Ken Powers addressed varied teaching methods through scaffolding content knowledge to establish a learning baseline for his students. He stated: “We do a lot of literacy-type strategies, including chunking text and breaking complex words and concepts down for student understanding.”

Ken Powers further explained that knowing his students’ ability levels is vital for acquiring words, terms, and phrases while learning the appropriate strategies. Ken explained how ability levels influence his instructional approach, “If it’s something we need to cover, we’re going to break it down into small groups, paying attention to diverse reading levels, chunking the text, and discussing as a group.” Ken spoke of his role as the SBAE teacher when instructing students: “I will lead the students through a discussion where I ask, what does the text mean to you? We typically do this with five to six sentences, not 10 to 12 paragraphs.”

Other participants used different instructional methods when discussing words, terms, and phrases in the classroom. This analysis contrasts classroom instruction models while emphasizing pedagogical practices. Mini Mouse indicated that his delivery is more direct [instruction] in the beginning when introducing new words, terms, and phrases. He clarified how using digital video, demonstrations, and discussion provided context for vocabulary terms or the concepts being studied: “I use a lot of presentations and give examples and visuals. I talk a lot at the beginning of the class to lead the discussion.” Mini Mouse further detailed how he incorporated student involvement in the lesson: “I’ll ask for a volunteer or randomly call on students in the class. I check for understanding and use probing questions before the lesson to see where they [students] are learning.” Otis reinforced Mini Mouse’s instructional methods when discussing words, terms, and phrase instruction: “I feel like sometimes we go backward [in education]; we throw big words out first, and they [students] become overwhelmed.” Otis’ frustration was more evident when discussing vocabulary instruction in the classroom: “We [teachers] have traditionally started with vocabulary first and then explain the term out of context.” Aloe Vera explained her approach as hands-on by providing a contextual foundation. She indicated: “We must [be] very hands-on in my program. We will go to the greenhouse and practice the concept or term I introduced in class”. Aloe Vera described the hands-on approach that encapsulated her teaching:

I would take different plants and line them up in the greenhouse so we could discuss, demonstrate, and practice cuttings, division, stem cuttings, and leaf cuttings. I would show them various ways to apply the term, and they [students] would demonstrate for me to assess their understanding.

Just as important as the material presented during the lesson, Aloe Vera also spoke about the value of post-instruction formative assessment:

After applying words, terms, and phrases in the lab, we [teacher and students] would return to the classroom and review vocabulary words and associate them with pictures, and students will take notes. I found this approach works best for my students to learn.

This type of multi-faceted lesson design, which includes introduction, application, assessment, and repetition, indicates a well-designed approach to learning words, terms, and phrases (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2012).

Assessment

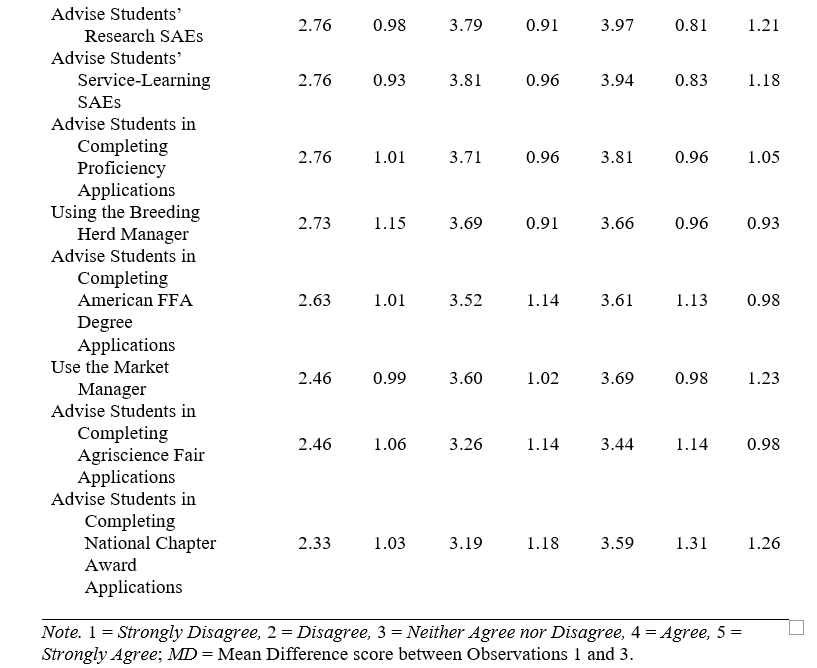

Participants discussed using formative and summative assessments in their classrooms during the interviews. Responses varied considerably between participants, including project-based assessment, traditional testing procedures, technology applications, and administratively defined testing. Participants generally fell between traditionally assessing student performance and using non-traditional assessment methods. When evaluating students’ knowledge, words, and concepts, Lee responded: “Since students don’t have to write the notes I give them, they can bring them to class for the test, but I won’t let them photocopy.” Although he referred to summative examination, the interview questions may have limited his response. Lee had little regard for rote memorization examinations and believed that allowing students to use their notes on the exam provided more significant potential for student success.

Mini Mouse also shared this sentiment when asked to explain the purpose of assessments during and after a lesson or unit plan. Mini Mouse stated: “I don’t give a lot of tests.” The researcher probed for further explanation of how students in Mini Mouses’ classes were assessed. His response was distanced from traditional assessment to more student-driven activities where he could observe concepts and the acquisition of words, terms, and phrases. Mini Mouse explained: “I ask many questions before the lesson, and then we go out [to the mechanics lab] and apply the concepts and skills.” Pike Place explained a similar situation to Mini Mouse: “I coach them [students] to ensure the process is followed, and I assess their performance during their demonstration.”

Other participants indicated a more traditional approach to their assessment. Hank explained that his literacy exams typically include 30 to 40 questions with multiple choice, true and false, fill in the blank, and matching terms with definitions. Otis explained that his use of Scantron®, paper exams, and Kahoot, a game-based learning platform, are the typical assessment types used in his classroom.” Winnie described assessment in a less traditional sense. She said: “I usually have a matching quiz with multiple uses of the word being examined. Having this type of assessment allows students to move beyond simple recognition.”

While interviewing Winnie and probing deeper into assessment methods, she began to be more open about using technology for the formative assessment of agricultural literacy. Winnie, a young teacher (< five years’ experience), and Otis (> ten years’ experience) were the only teachers to mention using applications such as Kahoot or Quizlet platforms for assessment. Her description of the applications provided context for how she uses them in the classroom: “Typically, I ask the students to take the words from the lesson and develop phone-based quizzes that can then be shared with other students in the class.” The researcher probed for further understanding regarding the type of assessment used from these applications: “I guess I use them as more formative assessment, like a bell ringer for understanding if my students have grasped the material.” Winnie explained her rationale for using application-based programs:

In grades 7 through 9, we use technology. Kids don’t like making the quizzes but do enjoy playing the game. When the students are developing their online quizzes, they must type the terms and definitions before they can play the game.

Learning Environment (Student Controlled)

Teachers discussed the importance of the formalized student-centered learning environment and the characteristics innate to each student. Many teachers discussed the environmental conditions of learning and geography’s impact on presumptions, misconceptions, and breaking away from family-based lexicons to be literate. Participants also described education challenges when teaching words, terms, and phrases to students with learning disabilities and the role gender has in education. Otis described geographical location as limiting when learning words, terms, and phrases. Otis explained: “My kids believe that GMO’s [genetically modified organisms] will kill you, so we make a stand and deliver on the difference between sustainable, organic versus traditional farming, populations, and discuss the amount of food a traditional vs. organic producer can provide to the public.” When describing the methods used to provide instruction, Otis explained: “Most of the time, it is self-directed learning and then research for their information.”

Winnie and Jane shared their perceptions of gender and special education populations in their classrooms. Winnie described the challenges of being female when teaching young men. Winnie said: “Being a woman, boys will talk differently around me. I have to figure out how to connect with them and find the connection between how they talk and think.” Winnie further explained how family influences student learning in a rural town by saying: “A lot of time when you teach in the country, people are set in their ways. For example, I drive a Ford, the only truck I’ll ever drive.” The researchers followed Winnie’s response and redirected the question to address how she reaches these students: “They [students] want to come at it their way, and you have to figure out how to accept and encourage their views and redirect them to the correct terminology.”

Like Winnie, Jane had experienced issues with word appropriateness and questioned her ability to provide meaningful instruction to special education students. Specifically, she discussed her difficulty differentiating her teaching when focusing on agricultural literacy. Jane admitted: “I do struggle with simple things . . . I get a lot of 504 [special education modification plans] and IEP [Individualized Education Plan] students with much lower rates of literacy and possessing literacy skills.” This varied ability-level transition has been difficult for Jane: “I’m old school. I use the vocabulary in the chapters [textbook] a lot.”

Foundational Competencies (Skills/Materials)

During the interviews, teachers were asked to describe their students’ foundational literacy skills and cognitive levels when asked to learn new concepts or terms. Sub-themes emerged within Foundational Competencies and were divided into three subcategories: 1) reading or writing to learn, 2) developing knowledge and understanding, and 3) educational materials (digital and text-based instruction).

Reading or Writing to Learn

Teachers indicated similar ideas and methods when asked about their perceptions of how foundational knowledge of student literacy is established. All participants agreed that educational growth can only occur by establishing a solid literacy foundation. Ken Powers said: “I will use the Lexile levels of the material we are going to learn.” Ken Powers referenced several web-based Lexile generators (Lexile.com, Renaissance.com) for determining the reading level of written text for his students: We’re [agriculture educators] looking at what they [students] know: concepts, demonstration of contextual vocabulary, and their current knowledge of the term or concept being discussed.” Otis addressed the importance of establishing a context for learning before introducing more complex vocabulary during his lesson. He stated: “What we need to do is ask students if they understand how this [concept] works. If they say yes, then build on that foundation before we take notes on the concept.” Otis’s explanation of establishing foundational learning was also present in his use of technology:

I also use Instagram as an example in class and discuss a company that has a flash sale on Instagram that all my students are familiar with and then determine if they [students] understand concepts such as the law of demand. This helps me give them a common starting point since all my students use Instagram.

Hank agreed with his peers, citing the need for solid foundations in literacy before introducing more advanced content. He said: “If they’re [students] not content literate in words and concepts at the beginning of the lesson, then it’s going to be hard to hammer those skills home during the lesson.” Aloe Vera also believed the key to establishing a solid foundation for learning was determining where students are in their learning. Aloe Vera incorporates discussion and writing to assess student knowledge and then adjusts her instruction accordingly. She said: “I would ask someone to describe what they wrote. Right or wrong, the answer doesn’t matter in the beginning. We’re [teacher and students] just thinking out loud.”

Developing Knowledge and Understanding

All participants echoed the importance of teaching words, terms, and phrases. Teachers described the challenges of determining foundational knowledge before introducing new concepts and vocabulary. These challenges led to discussions with each participant about the role of learning words, terms, and phrases in agriculture and the instructional methods each participant used to improve student understanding and learning. Mini Mouse described how words and terms are introduced in a forestry lesson. He said: “I might introduce the term forestry first, then describe the term dendrology. I’ll put up a list of terms and run [a copy] the definitions for students before I start the actual teaching.”

Hank described teaching disciplinary literacy, using contextual vocabulary in his classroom, and utilizing a comparative discussion between general and disciplinary literacy. He explained:

I like to use everyday vocabulary [general literacy] as a point of reference when I teach terms and concepts. I give a point of reference, especially when teaching tool identification. Most people have a hammer or a screwdriver at home, so these items are well-known to students. Students don’t have palm sanders, skill saws, stationary equipment, or specialized tools.

Hank described his application of words, terms, and phrases in the classroom: “I describe each of the disciplinary vocabulary words and demonstrate to students how to use the tool and that often the tool’s name is similar to its function.”

Educational Materials (Digital and Text-Based Instruction)

Richards et al. (1992) defined readability as: “How easily written materials can be read and understood.” (p. 306). Each participant mentioned the use of digital and text-based learning materials. The role and use of materials varied considerably between participants during instruction. Teachers reported limited use of textbooks because of low availability and outdated information. Most indicated that textbooks were used as a supplement or reference for students, while others cited the use of textbooks for use during their absence from the classroom when a substitute teacher was present. Lee described using textbooks in the classroom: “Textbooks don’t leave the classroom, but they are used as a resource. I only ask students to use them when a sub [substitute teacher] covers my classes.” Winnie explained the difficulty related to the readability of CTE texts and her students’ abilities to comprehend textbook-based material for comprehension. She supported Lee’s analysis: “CTE texts are written at an extremely high reading level, and I just don’t understand why.”

Some teachers indicated that although textbooks are seldom used, text-based material from the Internet, research journals, trade magazines, and other sources were much more prevalent in their classrooms. Digital text delivered by tablet, computer, or mobile phone was more prominent during instruction. Teachers also described that non-textbook-based materials were more accessible to locate and were sometimes more up-to-date regarding agriculture professions when compared to textbooks. Big Country utilizes text-based materials from the Internet and reputable online publishers, “I will give the students journal articles from trade magazines like Ag Daily, Coop Magazine, Progressive Farmer, etc.

Otis and others discussed the types of materials used for text-based reading and the methods used to provide materials to students. Otis stated:

We use the Internet and CEV [Internet-based curriculum platform] because I can edit the curriculum to fit the needs of my students. I like to give them a handout or something on their Chromebook. This way, they [students] can work with me and keep on task while I teach.

Lee agreed with his peers regarding the digital delivery of text and supported his rationale for allowing personal technology devices in the classroom: “I try to utilize their [student’s] technology because we’re not going to win, so I might as well let students use them [technology] for appropriate purposes.”

Limitations (Administration)

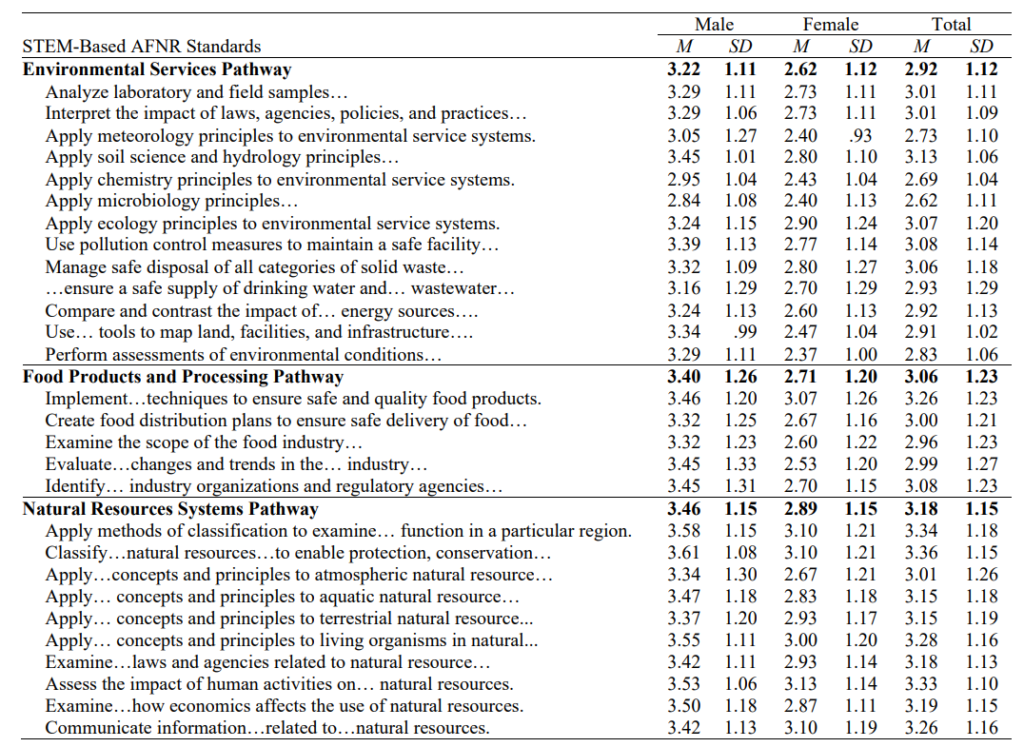

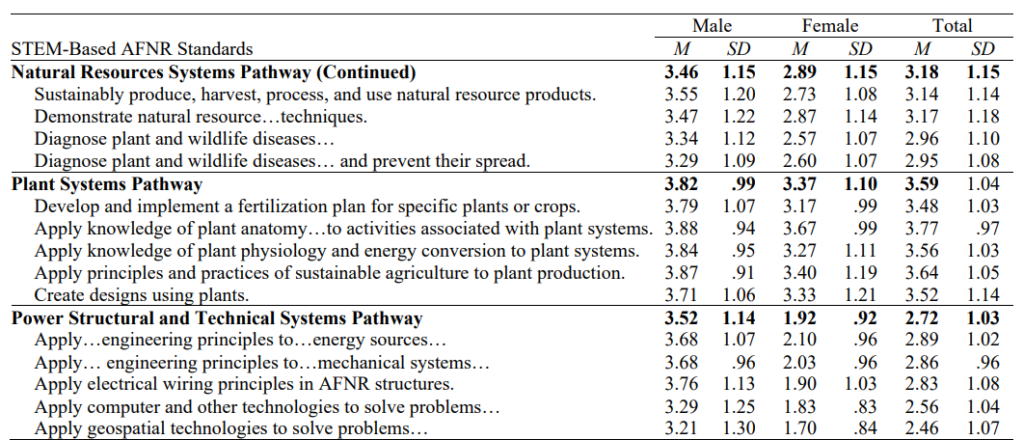

Throughout the interviews, teachers described perceived limitations regarding learning words and phrases in the agriscience classroom. A uniform response highlighted the impact of Common Core State Standards (CCSS), Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resource standards (AFNR), Alabama content standards, and administrative limitations for classroom instruction. The discussion of standards inclusion in daily instruction was mentioned as an administrative requirement to what teachers believed was quality SBAE instruction. Pike Place explained how she incorporates CCSS, AFNR, and Alabama content standards in her instruction: “When I give vocabulary tests, I take the standards we have to meet (AFNR, CCSS, and Alabama) and make them understandable for the age level I work with.”

Participant statements focused on administrative oversight of literacy instruction, administrative-directed literacy assessments, and short-lived interest in standards-based instruction. Mini Mouse described in detail his experience with administrative oversight between literacy and agriscience education: “A couple of years ago, when we were getting slammed with literacy [mandates] to introduce more reading, they [administration] wanted us to come up with some activities that helped with reading and writing standards.” Mini Mouse further explained that over time, administrative interest in literacy waned, and other mandates became their focus:

They [administration] backed off, which is why I feel we get on whims a lot and then get tossed from one thing to another. It’s not that the administration wants us to stop incorporating standards, but they move on to something different. I think they assume that we keep doing what we are doing.

Jane told a similar story regarding administrative oversight in her classroom regarding literacy instruction: “The curriculum specialists are pushing so hard for us to move to project-based learning and give kids a choice of assignments that we [teachers] don’t have the freedom to teach traditional literacy instruction.”

Conclusions, Implications, and Recommendations

The findings of this study revealed that SBAE teachers were engaged in various literacy activities. However, student writing was only seldom mentioned. Participants used explicit explanations to introduce students to new agricultural concepts and vocabulary, motivated their learning through group work, and led them in project-based activities to apply new ideas in real-life situations.

When the teachers were asked to explain the methods for literacy instruction, our teachers used varying materials for student instruction, e.g., by having students review articles in periodicals, using internet-based learning platforms (CEV), comparing arguments, or creating quizzes using web-based applications. However, more evidence of sustained individual writing needed to be shared to apply new concepts to support using words, terms, and phrases for developing student literacy. This finding supports Roberts et al. (2008) that high self-efficacy in group work, limited answers, or developing web-based quizzes may be evident yet is manifested in low self-efficacy if students were to be tasked with individual writing prompts. For example, teachers should have reported using a gradual release of responsibility where students were helped to locate meanings, relate words to other words, extricate words from their initial context, and generate new contexts with emerging expertise. Participants relied primarily on contextual vocabulary teaching methods where students explained new vocabulary terms orally, allowing teachers to scaffold students’ usage of words, terms, and phrases during classroom instruction and project-based activities.

Understanding the assessments used to measure speaking, listening, and writing using specialized words and terms (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2012) in SBAE provided insight into how teachers determine student growth. Teachers listened closely to students’ conversational responses and used formative assessment to redirect their understanding of concepts and vocabulary. Instead, teachers reported that changing students’ lexicon to define content-driven vocabulary was too difficult. Instead, teachers would list the vocabulary words in a handout. These findings suggest that teachers in this study do not fully implement Bandura’s (1997) model of interaction between the person, environment, and behavior. Instead, instruction of words, terms, and phrases was predominantly spoken and not emphasized through independent student writing. The implications of this de-emphasis indicate that students may not acquire vital skills in agricultural literacy because SBAE teachers do not possess foundational literacy instruction and training skills.

Consequently, students need to develop speaking, listening, and writing skills using specialized words and terms in agriculture, as supported by Shanahan and Shanahan (2012). This means they must acquire speaking, reading, and writing tools to learn about agriculture with their teachers and then be able to write independently by receiving foundational literacy skills. Park et al. (2010) reinforced the importance of student literacy and emphasized the nature of agricultural education as a content application. The work of Rosenthal and Zimmerman (1978) supports this finding as high self-efficacy in one area (content instruction) is juxtaposed against low self-efficacy (literacy instruction efficacy) of the teacher. Ultimately, the data supported the idea that knowing and teaching content must likely be reinforced through student writing for improved literacy.

Administrative oversight of the instructional processes is a concept that has been introduced previously in education. Participants expressed frustration with administrative oversight related explicitly to literacy instruction and the development of students to possess speaking, listening, and writing skills in agriscience. Teachers reported that vocabulary was a mandated component of the agriscience curriculum. However, their instruction needs to be improved to determine the best practices for improving students’ ability to become literate and develop the necessary skills for success. The implications of this mandated oversight of literacy instruction are the removal of the agriscience teacher as the content area expert and their expertise in creating multiple pedological styles to improve the literacy of students in agriscience (Shoulders & Myers, 2013).

Participants should build on their present writing activities to add extended individual writing to the learning process and hands-on application of new concepts (Park et al., 2010) to reinforce literacy instruction. For example, students could use content-literacy guides to focus their textbook reading on essential ideas and writing activities in SBAE classrooms. They could follow up their project-based activities by writing formal lab reports from their observational notes. They could consolidate their new vocabulary knowledge by applying new terms and new concepts by writing for synthesis, and they could publish their ideas on Internet websites to share them with other students and professionals beyond the classroom. Such writings could serve as summative evaluations of students’ understanding of concepts introduced in class and appropriate usage of new vocabulary in the discipline.

The findings indicated a perceived need for an administrative understanding of pedagogical practices for literacy instruction in the SBAE classroom. Participants spoke of frustration, mandates, and limited instructional models for developing students’ understanding of literacy. It can be concluded that administrators need to understand better the intricacies and specialized skills required for the instruction of secondary agriscience education. It is recommended that SBAE teachers and administrators discuss how writing in the agricultural education curriculum could develop a deeper understanding of the best practices and proven methods for instructing students to develop literacy skills in agriculture. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, SBAE teachers should highlight the interconnection of student experiences in labs, greenhouses, and other agricultural experiences. These conversations and collaborative efforts could reduce the frustration and perceived oversight participants felt as limiting their expertise.

We recommend that teachers continue to develop their instruction methods for incorporating speaking, listening, and writing in the secondary agriscience education curriculum. The outcome of such development could further SBAE students’ literacy beyond just the acquisition of agricultural knowledge. Instead, students will be better prepared as future advocates and consumers of agricultural services and have opportunities to extend factual discussions to more audiences. We expect this new emphasis on speaking, listening, and writing using specialized words and terms in agriculture to provide students with the literacy tools agricultural professionals use to read and write to learn agriscience.

References

Act of July 2, 1862 (Morrill Act), Public Law 37-108, which established land grant colleges, 07/02/1862; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1996; Record Group 11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives

Alston, J. A., & English, C. W. (2007). Technology-enhanced agricultural education learning environments: An assessment of student perceptions. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5032/Jae.2007.04001

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Clemons, C. A., Lindner, J. R., Murray, B., Cook, M. P., Sams, B., & Williams, G. (2018). Spanning the gap: The confluence of agricultural literacy and being agriculturally literate. Journal of Agricultural Education, 59(4), 238–252. doi: https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2018.04238

Blythe, J. M., DiBenedetto, C. A., & Myers, B. E. (2015). Inquiry-based instruction: Perceptions of national agriscience teacher ambassadors. Journal of Agricultural Education, 56(2), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.02110

Brown, N. R., Roberts, R., Whiddon, A. S., Goossen, C. E., & Kacal, A. (2015). The essence of the lived experiences of urban agricultural education students. Journal of Agricultural Education, 56(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.01058

Cremin, L. A. (1967). The transformation of the school: Progressivism in American education 1879-1957. Vantage Press.

Delbecq, A. L., Van de Ven, A. H., & Gustafson, D. H. (1975). Group techniques for program

planning: A guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Foresman.

Fuhrman, N. E., & Rubenstein, E. D. (2017). Teaching with animals: The role of animal ambassadors in improving presenter communication skills. Journal of Agricultural Education, 58(1), 223-235. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2017.01223

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Sage Publications.

Harris, T. L., & Hodges, R. E. (1995). The literacy dictionary: The vocabulary of reading and writing. International Reading Association.

Hasselquist, L., Naughton, M., & Kitchel, T. (2019). Preservice Teachers’ Experiences in a Required Reading in the Content Area Course. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.02140

Hennink, M.M., Kaiser, B.N., & Marconi, V.C. (2016). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

Hess, A. J., & Trexler, C. J. (2011). A qualitative study of agricultural literacy in urban youth: What do elementary students understand about the agri-food system? Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(4) 1-12. https://doi.org/10.5032.jae.2011.04001

Kaiser, K. (2009). Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 19(11), 1632–1641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309350879

Lemley, S. M., & Hart, S. M. (2019). Using inquiry to develop agricultural education preservice teachers’ disciplinary literacy pedagogy. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(4), 149-163. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.04149

McKibben, J. D., Giliberti, M., Clemons, C. A., Holler, K., & Linder, J. R. (2022). My ag teacher never made me go to the shop! Pre-service teachers’ perceived self-efficacy in mechanics skills change through experience. Journal of Agricultural Education, 63(3), 283–296. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2022.03283

McKim, A. J., Sorensen, T., Velez, J. J., & Henderson, T. M. (2017). Analyzing the relationship between four teacher competence areas and commitment to teaching. Journal of Agricultural Education, 58(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2017.04001

Kolb, A.Y., Kolb, D.A. (2012). Experiential Learning Theory. In N. M. Seel (ed), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_227

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Josey-Bass.

Park, T. D., & Osborne, E. (2007). A model for the study of reading in agriscience. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2007.01020

Park, T. D., Van Der Mandele, E. S., & Welch, D. (2010). Creating a culture that fosters disciplinary literacy in agricultural sciences. Journal of Agricultural Education, 51(3). 100-113. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2010.03100

Richards. J. C., Platt, J., & Platt, H. (1992). Longman dictionary of language and teaching and applied linguistics. Longman.

Roberts, G. R., & Ball, A. L. (2009). Secondary agricultural science as content and context for teaching. Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2009.01081

Roberts, G. R., Harlin, J. F., & Briers, G. E. (2008). Peer modeling and teaching efficacy: The influence of two student teachers at the same time. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(2), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2008.02013

Rosenthal, T. L. & Zimmerman, B. J. (1978). Social learning and cognition. Academic Press.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2012). What is disciplinary literacy and why does it matter? Topics in Language Disorders, 32(1), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0b013e318244557a

Schunk, D. H. (2004). Learning theories: An education perspective. Pearson.

Shoulders, C. W., & Myers, B. E. (2013). Teachers’ use of experiential learning stages in agricultural laboratories. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(3), 100-115. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae2013.03100

Smith-Hughes National Vocational Education Act of 1917, 45 C.F.R. § 104.56 (1960).

Smith, K. L., & Rayfield, J. (2016). An early historical examination of the educational intent of supervised agricultural experiences (SAEs) and project-based learning in agricultural education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(2), 146–160. https://doi.org/doi:10.5032/jae.2016.02146

Tummons, J., Hasselquist, L., & Smalley, S. (2020). Exploring content, pedagogy, and literacy strategies among preservice teachers in CASE institutes. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(2), 289-306. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.02289

Vallera, F. L., & Bodzin, A. M. (2016). Knowledge, skills, or attitudes/beliefs: The contexts of agricultural literacy in upper-elementary science curricula. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(4), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.04101

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Young, D. S., & Casey, E. A. (2018). An examination of the sufficiency of small qualitative samples. Social Work & Criminal Justice Publications. 500.

https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/socialwork_pub/500