Chris L. Hunt, Southwest R-V Public School, clhunt@uark.edu

Don W. Edgar, University of Arkansas, dedgar@uark.edu

Abstract

Preservice teaching experiences lay the foundation for agricultural education graduates to enter the teaching field (Lawver & Torres, 2011). The overall teacher candidate experience allows candidates to develop lessons and lead classroom learning events while participating in courses that allow them to actually be “students of education” (Edgar, 2007, p. 2). Furthermore, teaching-efficacy has shown to impact individual’s entrance to the field of teaching (Wolf, et al., 2010). The purpose of this study was to assess teaching efficacy and the relationship of teacher candidates and cooperating teachers via a structured communication instrument. To determine if a difference existed in teaching efficacy an ANOVA was used. The overall model was not significant (Between Groups, F = .57 and p = .69). Further analysis determined that no significant differences were seen in teacher candidates’ perceptions towards teaching when cooperating teachers’ use a communication tool (Between Groups, F = 1.63 and p = .18). Additionally, no significant difference was found between universities based on overall teaching efficacy and teacher candidate cooperating teacher ratings. Even though no significance was found between universities on teaching efficacy when the cooperating teacher uses the communication tool, it should be noted that the overall relationship with the teacher candidate has the possibility to effect the teacher candidates’ willingness to teach agriculture after graduation. Further research should be conducted to see the direct effects of the behaviors, personal factors, and the environment of preservice teaching. It is also suggested that future research be conducted to define the specifics of the behavioral factors, environmental, and personal factors in terms of agriculture education.

Introduction

Education in agriculture (agricultural education) at the secondary level is facing a crisis due to a shortage of qualified, dedicated, and passionate teachers (Kasspervauer & Roberts, 2007a). This shortage can be explained by taking a closer look at the preservice teaching experience to examine if efficacy and motivation is a deciding factor in teacher candidates’ willingness to enter the profession (Robinson, Krysher, Haynes & Edwards, 2010).

The relationship between cooperating teacher and teacher candidate has been found to be one of the key elements that affect the overall teaching efficacy of candidates and their decision to enter the teaching field after graduation (Edgar, 2007; Edgar, Roberts, & Murphy, 2011,2008; Kasspervauer et. al, 2007a; Roberts, Greiman, Murphy, Ricketts, Harlin, & Briers 2009; Roberts, Harlin, & Briers, 2007, Roberts, Harlin, & Ricketts, 2006; Roberts Mowen, Edgar, Harlin & Briers, 2007, Stripling, Ricketts, Roberts & Harlin, 2008; Wolf, 2011; Wolf et al., 2010).

Institutions at the post-secondary level are still trying to determine the reason for teacher shortages (Lavwer & Torres, 2011). Wolf (2011) suggested that studying teaching efficacy may be the potential solution to the teacher shortage in agricultural education. Preservice teaching experiences lay the foundation for agricultural education graduates to enter the teaching field (Lawver & Torres, 2011). Thus, the overall teacher candidate experience allows candidates to develop lessons and lead classroom learning events while participating in courses that them to actually be “students of education” (Edgar, 2007, p. 2).

Teaching-efficacy has shown to impact individual’s entrance to the field of teaching (Wolf, et al., 2010). Wolf et. al (2010) reported that “candidates reported a favorable view of their preparation, although their preparation was lower than their perceived sense of teaching efficacy” (p. 44). Wolf et. al (2010) also indicated that verbal feedback had a moderated positive relationship to candidates overall teacher self-efficacy. Teaching efficacy was originally defined by Berman, Mclaughlin, Bass, Pauly, and Zellman (1977) as “the extent to which a teacher believes he or she has the capacity to affect student performance” (p. 137). Self-efficacy and teaching efficacy can be directly related to the environment in which the individual interacts with. During the preservice teaching experience teacher candidates are exposed to several types of environments such as direct feedback, student compliments, personal confidence, classroom behaviors of students, support by cooperating teacher and school administration but the major environmental factor that research has indicated as the most important was communication between cooperating teacher and teacher candidate concerning feedback (Edgar, 2007; Edgar et al., 2011; Edgar et al., 2008; Kasspervauer et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2007a; Roberts et al., 2007b; Roberts et al., 2006; Shute, 2007; Whittington, McConell, & Knobloch, 2006; Wolf, 2011). Edgar (2007) further elaborated that structured communication played a vital role in understanding the relationship between the teacher candidate and cooperating teacher.

This study used structured communication (communication tool) to encourage communication about teacher candidate’s performance. The communication tool acts as the channel for cooperating teachers to provide feedback and recommendations to teacher candidates. Performance evaluations acted as a way for teacher candidates to grow and develop skills affecting their perceived classroom teaching abilities. Dewey (1981) suggested that meaning happens from language which is a two way street consisting of a sender and receiver in developing meaning and understanding. Researchers (Edgar et al., 2011; Edgar, et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2007; and Wolf, 2011) stated that teacher candidates gain knowledge about effective teaching when the cooperating teaching is willing to share ways of improvement. Congruent with this premise, Demoulin (1993) challenged cooperating teachers to “foster unique teaching techniques and give support and encouragement to teacher candidates” (p. 160).

The purpose of this study was to assess teaching efficacy and the relationship of teacher candidate and cooperating teacher via a structured communication instrument (tool). This study was a replication of a study done by Edgar (2007) but accomplished on a more diversified group as recommended. The reason for replicating this study was to determine if teacher candidates’ perceptions changed throughout the semester at multiple universities in order for the results to be more applicable to field experiences as a whole. Structured communication affects teacher candidates because it requires them to have a conference with the cooperating teacher on a bi- weekly basis in order to receive feedback on what he/she is doing right and what needs improvement so at the end of the preservice teaching experience they feel they are capable of effectively operating their own classroom. Research done by Edgar (2007) indicated that cooperating teachers are not effectively communicating with teacher candidates during the preservice teaching experience. His findings suggested that by using structure communication, cooperating teachers along with teacher candidates are required to communicate better on what the teacher candidate is excelling in and what the teacher candidate could do to improve on.

Theoretical Frameworks

As explained by Bandura (1986) the social cognitive theory attempts to explain how people acquire and maintain certain behavioral patterns. According to Rotter (1954), “the major or basic modes of behaving are learned in social situations and are inextricably fused with needs requiring for their satisfactions the mediation of other persons” (p. 84). Bandura (1997) regarded self-efficacy as one of the most important factors contributing to an individual’s behavior. The idea that every individual has the potential to influence change, regardless of their skill level, was the key to the social cognitive theory (Pajares, 2002). Social learning theory can be used to explain and predict individual or group behavior and used to help identify ways in which behavior can be modified or changed for favorable outcome (Whittingon et al., 2006). Parjares (2000) stated that social cognitive theory is “a view on human behavior in which the beliefs that people have about themselves are key elements in the exercise of control… in which people are producers of their own environments and social systems” (p. 2). Bandura (1986) summarized the social cognitive theory by saying that “what people think, believe and feel effects how they behave” (p. 25).

From the social cognitive theory standpoint, the teacher candidate and cooperating teacher relationship and teacher candidates’ perceptions of their abilities to teach influenced their behavior (Bandura, 1997). The relationship between teacher candidates and cooperating teachers have a major effect of the observational learning that takes place during the student teaching experience. Observational learning according to Schunk et al. (2008), expanded the range and rate of learning over what could occur if each response had to be performed and reinforced for it to be learned. Therefore, teacher candidates’ value the perceptions of their relationship with their cooperating teacher (Edgar, et al., 2008). Their perceptions of their ability to teach was a reflection of self-efficacy based off the social cognitive theory.

Self-efficacy was defined by Bandura (1986) as “people’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of actions required in order to attain designated types of performance” (p. 391). Self-efficacy affects willingness to participate in activities, amount of effort put forth on a specific task and persistence to continue when task seems challenging. This theory postulates that individuals with high efficacy had intrinsic interest and deep engrossment in activities. Bandura (1997) concluded that “efficacy is a generated capability in which cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral skills must be organized to serve innumerable purposes” (p. 17). Individuals with high-efficacy approach challenging and demanding tasks with assurance that they can exercise control over them and have the staying power to overcome obstacles and set-backs (Bandura, 1994; Wolf, 2011).

Teaching efficacy was originally defined by Berman, Mclaughlin, Bass, Pauly, and Zellman (1977) as “the extent to which a teacher believes he or she has the capacity to affect student performance” (p. 137). Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) defined teaching efficacy as “… a judgment about his or her capabilities to bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning, even among those student who might have learning difficulties or are simply unmotivated” (p. 1). Edgar, et al. (2011) added that teaching efficacy was more of a personal factor and defined teaching efficacy (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998) based on “ the teacher’s belief in his or her capabilities to organize and execute action required to successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (p. 22).

Tschannen -Moran et al., (1998) realized that many teacher candidates lack the understanding or complexity of teaching. Therefore, teacher candidates expectations change because their roles change and realize their expectation of students in the learning environment and actual student commitment to learning are different causing caps between teacher and learner (Edgar, 2007). In terms of instruction and classroom management, Bandura (1993) suggested that classroom environment is related to teacher’s instructional efficacy. Teachers who have more instructional efficacy use more of class time for instruction and provide students who have difficulty learning with the help they need (Gibson & Dembo, 1984). Teachers with high instructional efficacy tend to “foster mastery experiences for their students,” according to Bandura (1994, p. 140). Personal teaching efficacy has been found to increase during the first year of teaching.

Many researchers conducted studies focused on the student teaching experience as a “capstone” event for preservice candidates (Edgar et al., 2011; Edgar, 2007; Kasperbauer & Roberts, 2007a; Roberts et al., 2007; Roberts et al, 2009; Wolf, (2007). Edgar et al., (2011) elaborated on the relationship of cooperating teachers and teacher candidates by concluding that a students’ perceived teaching efficacy and age was a positive factor in the relationship between teacher candidate and cooperating teachers. Roberts, Harlin, and Briers (2007) assessed the relationship of teacher candidate and cooperating teachers’ relationship based on personality type. The researchers noted that the personality type of a cooperating teacher greatly influenced the overall efficacy and relationship of the teacher candidates.

SMCR (Source-Message-Channel-Receiver) guides the framework of this study towards communication. The channel was considered the most important factor the SMCR model analyzes for this study. The channel can come in two ways: verbal and written. Verbal channels include one-on-one sit down session where the cooperating teacher provides suggestions to the teacher candidate, informal talks during lunch, and round table talks with other teachers if in a multiple teacher program. Written channels includes weekly journals where the cooperating teachers writes down suggestion and notes on how the teacher candidate can improve, structured communication tool where the teacher rates the teacher candidate on different constructs, or any other means of writing down their observations of the teacher candidate.

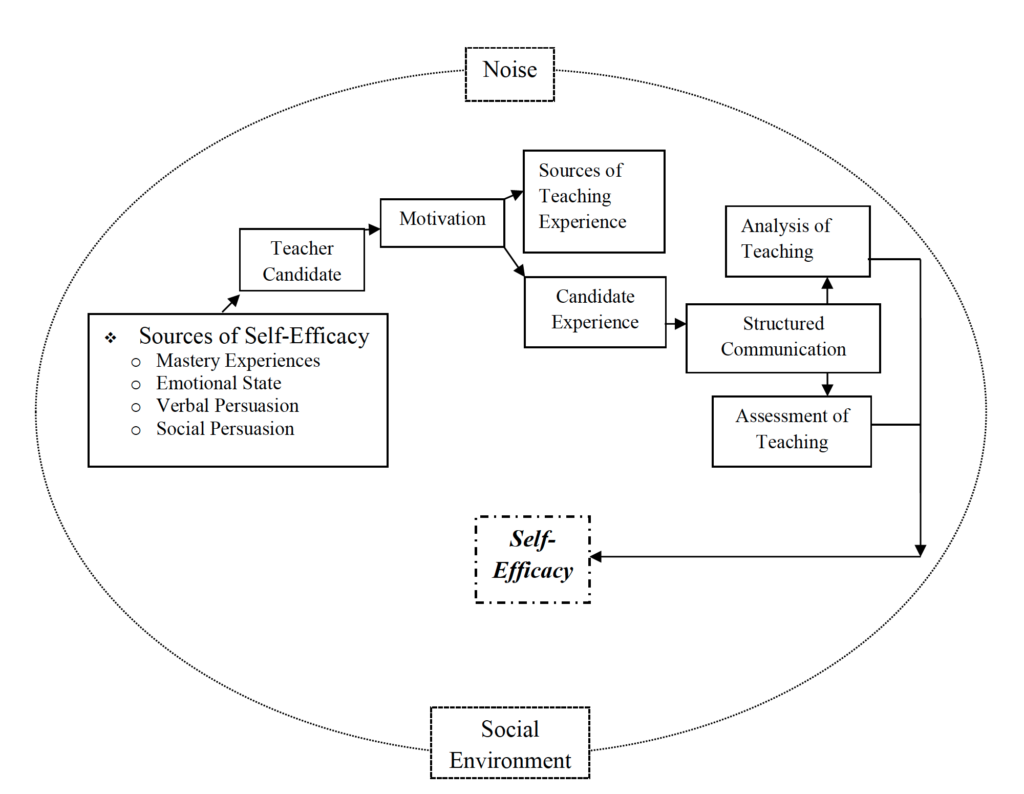

For the purpose of this study the receiver (SMRC) is the teacher candidate, because they are the intended receiver of the information given through structured communication. Feedback is given through the communication tool and it is the job of the receiver/teacher candidate to take the feedback and incorporate in to improve or ignore feedback. The teacher candidate and cooperating teacher feedback can have a direct relationship towards teaching efficacy. If feedback is always negative, teaching efficacy will decrease while if the feedback is positive teaching efficacy will increase. In the case of teacher candidates and cooperating teachers, noise could be comments made by students, parents, school faculty, or community leaders. Figure 1 displays the conceptual and theoretical frameworks of this study.

Figure 1. Conceptual and theoretical framework model. Adapted from Edgar, 2007.

Methodology

The purpose of this study was to assess teaching efficacy and the relationship of teacher candidates and cooperating teachers via a structured communication instrument that allows for direct feedback from the cooperating teacher to the teacher candidate in an effort to determine if teacher candidates’ perceptions of their teaching abilities change throughout the semester.

This study was guided by the following hypotheses:

Ho1: There will be no significant difference in teaching efficacy based on cooperating teachers’ use of a communication tool between universities.

Ho2: There will be no significant difference in teacher candidates’ perceptions towards teaching when cooperating teachers’ use a communication tool.

Ho3: No significant difference will be found between universities based on overall teaching efficacy and teacher candidate cooperating teacher ratings.

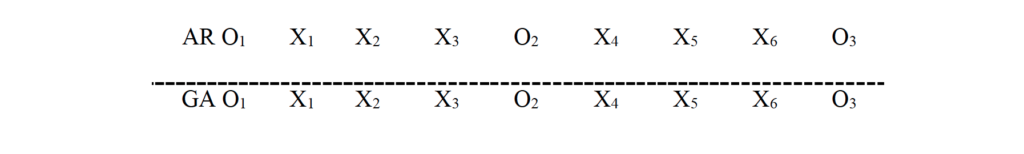

This study used a quasi-experimental design with a non-random sample through a time- series design (#14) (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). Campbell and Stanley (1963) defined: “a quasi-experimental design as there are many natural social settings in which research persons can introduce something they lack the full control over the scheduling of experimental stimuli which makes it a true experiment” (p. 34).

A priori was set at .05 (alpha) according to reviewed literature and the concerns of committing a type two error. The research was conducted based off the following design:

Figure 2. Research design for study at two universities.

A typical student teaching semester begins with course work (block) for the first four weeks of the semester. The final twelve weeks of the semester are considered the student teaching experience. The first measurement of teaching efficacy (O1) was taken during the last week of block classes or the fourth week of the teacher candidate experience. The second measurement of teaching efficacy (O2) was taken during the sixth week of the 12 week student teaching experience at a mid-semester meeting between teacher candidates and their respective university (University of Arkansas and University of Georgia) supervisor. The third (O3) and concluding teaching efficacy measurement was taken at the end of the 12 week student teaching experience. The experimental variable (Structure Communication Form) (Xn) was introduced at the beginning of the 12 week student teaching experience, at the conclusion of the four week block course. The experimental variable was collected every other week for twelve weeks. The independent variable was identified as the communication between teacher candidate and cooperating teacher. The treatment in this study requires structure and measurement which was normal during student teaching.

The target population of this study was individuals enrolled in an agricultural education department with a teacher certification program which requires the student teaching experience at two purposely selected states. Data was collected the University of Arkansas (N = 27) in the spring of 2012 (n = 12) and 2013 (n = 15) and the University of Georgia (N = 32) in the spring of 2012(n = 12) and 2013 (n = 20). Participants from the University of Arkansas resulted in 100% participation and incomplete results from a few participants from University of Georgia resulted in a 94% response rate. Teaching efficacy data was collected at three points during the semester.

The communication instrument (tool) in this study is an adaption used by the Department of Education at Florida State along with Texas A&M University. The communication tool contained 12 sections of accomplished practices of the teacher candidate. The cooperating teacher was required to assign a ranking of Outstanding; Accomplished; Progressing; Needs Improvement; or Not Applicable or observed. The cooperating teacher and teacher candidate filled out the communication form every other week for the 12 weeks of the student teaching experience resulting in six conferences held. There was a comment and recommendation section for every suggested practice that the teacher candidate should complete. The comments and recommendations was presented to the teacher candidate in order for teacher candidates to constantly improve and have a valuable student teaching experience.

In order to measure teaching efficacy Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk Hoy (2001) developed a Teachers Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES) also known as the Ohio State Teaching Efficacy Scale (OSTEES). This instrument contains 24 items based off three major constructs, which each constructs has eight items. The three constructs are engagement, instruction, and classroom management. The reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha) for Engagement was .87, Instruction was .91, and Classroom Management was .90.

In order to study the relationship between teacher candidate and cooperating teacher a researcher developed instrument (Edgar et al., 2008; Kasperbaurer & Roberts, 2007b; Roberts, 2006) was utilized to collect perception data of teacher candidates about their relationship with their cooperating teacher. The instrument was designed to coincide with the background/demographics and teaching efficacy instrument. The cooperating teacher/teacher candidate relationship portion consisted of 43 items. Teaching/instruction construct consisted of nine statements, professionalism and personality constructs consisted of 10 statements a piece, while teacher candidate/cooperating teacher construct had 14 statements. The scale was used to establish the describe characteristics of the cooperating teacher as perceived by the teacher candidate. Face and construct validity was established through an expert panel of experts (Edgar 2007) and the reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s Alpha) for the relationship question was .78.

Findings

Participants in this study were 50.2% female with the remaining indicating male as gender. A major percentage of students identified themselves as being 21 (33.9%) or 22 (33.9) years of age and ranged in age from 21 to 27 years of age. The majority of participants identified themselves as white (89.8%) with the second largest group being Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (6.8%). The remaining participants reported being American Indian/Alaskan Native (1.7%) and one participant (1.7%) did not accurately report ethnicity and was removed from this portion of the study. The greatest amount (57.6%) of respondents indicated they were enrolled in seven to eight semesters of high school agriculture with the rest indicating 1 to four semesters of secondary agriculture classes.

Hypothesis One

Hypothesis one stated that there will be no significant difference in teaching efficacy based on cooperating teachers’ use of a communication tool between universities. The independent variable under examination was the communication tool, while the dependent variable was teacher candidates teaching efficacy. To determine if a difference existed in

teaching efficacy an ANOVA was used. Table 1 displays the results found. The overall model was not significant (Between Groups, F=.568 and p=.687). The null hypothesis was accepted.

Table 1 ANOVA of Overall Teaching Efficacy

| df | SS | MS | F | p | ɳ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 4 | 1.43 | .37 | .57 | .69 | .04 |

| Within Groups | 54 | 33.93 | .63 | |||

| Total | 58 | 35.36 |

Hypothesis Two

Hypothesis two stated that there will be no significant difference in teacher candidates’ perceptions towards teaching when cooperating teachers’ use a communication tool. The dependent variable under examination was teacher candidates’ perceptions of teaching. The independent variable under study was the communication tool used by cooperating teachers. To determine if a difference existed in teacher candidates’ perceptions towards teaching, an ANOVA was used (see Table 2). The overall model was not significant (Between Groups, F=1.631 and p=.180). The null hypothesis was accepted.

Table 2 ANOVA of Overall Teacher Candidate Perception of Teaching

| df | SS | MS | F | p | ɳ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 4 | .33 | .08 | 1.63 | .18 | .11 |

| Within Groups | 54 | 2.70 | .05 | |||

| Total | 58 | 3.03 |

Null Hypothesis Three

Null Hypothesis three stated that no significant difference will be found between universities based on overall teaching efficacy and teacher candidate cooperating teacher ratings. To determine if there was difference in teaching efficacy and teacher candidates/cooperating teacher relationship a MANOVA was used to test the hypothesis. The dependent variables under study include teaching efficacy and teacher candidate’s perceptions of their relationship at multiple universities. The use of the communication tool by the cooperating teacher was the independent variable under examination. Table 3 illustrates the effects of the independent variable (structured communication) upon the dependent variables (teaching efficacy (TE) and relationship level (RL) measured at three points throughout the preservice teaching experience. A Pilia’s Trace significance value of .149 with an F=1.548. Effect size (ɳ2)) calculated at .10 and power at .66. The overall model was not significant therefore the null hypothesis was accepted.

Table 3 MANOVA of Teaching Efficacy and Teacher Candidate/Cooperating Teacher Relationship

| df | SS | MS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | |||||

| TE | 4 | 1.43 | .36 | .57 | .15 |

| RL | 4 | 1.84 | .46 | 2.44 | |

| Error | |||||

| TE | 54 | 33.93 | .63 | ||

| RL | 54 | 10.16 | .19 | ||

| Total | |||||

| TE | 58 | 35.36 | |||

| RL | 58 | 12.00 |

Conclusion and Recommendations

Because the sample (teacher candidates enrolled in the field experience at the University of Arkansas and the University of Georgia) under study was not randomly selected, the following conclusions were drawn on based on the findings and apply only to the population of this study.

- When cooperating teachers use a communication tool during the preservice teaching experience there is no overall significant difference in preservice teachers’ teaching efficacy at multiple universities.

- When cooperating teachers use a communication tool during the preservice teaching experience there tends to be no overall significant difference in preservice teachers’ perceptions towards teaching at multiple universities.

- When cooperating teachers’ use a communication tool during the preservice teaching experience there tends to be no significant difference in teaching efficacy based off the teacher candidates/cooperating teacher relationship.

Discussion and Implication

The purpose of this study was to assess teaching efficacy and the relationship of teacher candidate and cooperating teacher through a structured communication instrument at multiple universities. This study attempted to examine the factors that affect preservice teachers such as motivation, teaching efficacy, and the relationship between the cooperating teacher and preservice teacher.

Null Hypothesis One

There was no significant difference in teaching efficacy based on cooperating teachers’ use of a communication tool between universities. Teaching efficacy was originally defined by Berman, Mclaughlin, Bass, Pauly, and Zellman (1977) as “the extent to which a teacher believes he or she has the capacity to affect student performance” (p. 137). Edgar, et al. (2011) added that teaching efficacy was more of a personal factor and defined teaching efficacy based off. (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998) as “the teacher’s belief in his or her capabilities to organize and execute action required to successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (p. 22). Even though no significance was found, through ANOVA analysis, in teaching efficacy when the cooperating teacher uses a communication tool it should be noted the preservice teachers efficacy increased from the beginning of the student teaching experience to the end of the preservice teaching experience which correlates to previous research by Edgar, 2007; Kasspervauer & Roberts, 2007a; Roberts et. al., 2009; Whittington et. al., 2006, Wolf et al., 2010).

Roberts et al. (2007) suggested that teachers who believe strongly in their teaching efficacy will be more likely to foster self-efficacy in their students through development of challenging and engaging learning environments. Teacher candidate’s expectations change because their roles change. Preservice teachers also realize their expectation of students in the learning environment and actual student commitment to learning. Research by Edgar (2007) identified the difference in learning environment and student commitment to address the gap between teachers and learners.

Null Hypothesis Two

Determining what motivates college graduates to enter the field of teaching can be address by looking at individual expectations and individual success. Harm and Knobloch (2005) suggested that “needs theory relates to job satisfaction, when the three higher orders of needs (self-esteem, autonomy and self-actualization) were major factors in job satisfaction than teachers with lower satisfaction” (p. 103). Data analysis proved there was no significant difference in teacher candidates’ perceptions towards teaching when cooperating teachers’ use a communication tool.

In terms agriculture education internal motives typically don’t play a role in an individual’s reasoning for pursuing a career as an agriculture educator. Shoulders and Myers (2011) concluded that beliefs come from various areas of an individual’s life. Shoulders & Myers (2011) also noted that social beliefs shape a professional’s identity and is one factor of why they are motivated to teach. In order to further examine teacher candidates’ perception of teaching examination of the demographic information of willingness to teach agricultural science and plans after graduation. In terms of willingness to teach agricultural science the participants had a higher likelihood to teach agriculture science at the beginning of the student teaching, while there was decrease in willingness to teach by the end of the student teaching experience.

The preservice teachers’ plans after graduation leads the researcher to believe that the preservice teaching experience provides actual work experience and opens up other possibilities for the teacher candidates who realize they are not ready to teach just yet. The data analysis of plans after graduation indicated that preservice teachers were more likely to teach agriculture right after graduation but by the end of the student teaching experience the participants were unsure of their plans after graduation. Three major causes can be attributed to the decline in teacher candidates’ willingness to teach after graduation. Causes being the relationship with their cooperating teachers, their personal belief of their teaching efficacy, and the overall preservice teaching experience.

Null Hypothesis Three

Determinism as considered by Bandura (1978) were simply “understanding actions determined by a sequence of causes.” Schunk, (2000) further addressed human behavior by saying that “triadic reciprocity or reciprocal interaction among behavior, environmental variables, and personal factors” (p.80). Reciprocal determinism is used in the study to examine the cyclical nature of the student teaching experience (behavior), age, gender, teaching efficacy(personal factors), and relationship between cooperating teacher and teacher candidate (environment). The concept of reciprocal determinism is the major component of the social cogitative theory which is used at foundation theory for this study. No significant difference will be found between universities based on overall teaching efficacy and teacher candidate cooperating teacher ratings. A MANOVA was used to test the hypothesis and to determine if there was difference in teaching efficacy and teacher candidates/cooperating teacher relationship. Even though no significant was found it should be noted that the personal factors, behavior, and the environment has the potential effect the overall preservice teaching experience.

To better understand the effects of the communication tool examination of the structured communication should be examined. This study identified the receiver will be the teacher candidate, because the teacher candidate is the intended receiver of the information given through structured communication. Feedback is given through the communication tool and it is the job of the receiver/teacher candidate to take the feedback and incorporate in to improve or ignore. The relationship between the cooperating teacher and the teacher candidate was directly related to the communication tool. Roberts et al. (2006) concluded that teacher candidates’ perceptions of the relation between cooperating teachers and teacher candidates were not an indicator of the teacher candidate’s desire to teach. Therefore, it was important to note that the relationship between cooperating teachers and teacher candidates will change from time to time throughout the preservice teaching experience (Roberts et al, 2006). Even though no significance was found in between universities on teaching efficacy when the cooperating teacher uses the communication tool, it should be noted that the overall relationship with the teacher candidate has the possibility to effect the teacher candidates’ willingness to teach agriculture after graduation.

Recommendation

Reciprocal determinism is used in the study to examine the cyclical nature of the student teaching experience (behavior), age, gender, teaching efficacy(personal factors), and relationship between cooperating teacher and teacher candidate (environment). Because the experience of student teaching is so determining towards how preservice teachers value their abilities (efficacy), understanding the communication that occurs from and to them is imperative.

Although the tool used in this study (and previous) did not find significant differences, the data does tell us that there is an effect occurring but not at a significant magnitude. It is firmly believed that without evaluation and it being specific, learners do understand what they know and not know. It is recommended that all cooperating teachers and student teachers gain competency in communicating about aspects of the student teaching experience.

Communication occurs daily in our professional and personal lives. The impact of communication can add value or detract from learning. Degree programs are designed to teach skills towards teaching and agriculture but there is not normally a parameter for cooperating teachers to frame their leadership towards student teachers. Although this communication tool does not significantly affect efficacy, perceptions or the view of the relationship; communication and experiences shape individuals abilities. It is recommended that based on students and cooperating teachers that all universities with teacher education degrees in agricultural education determine how to best implement a formal process for cooperating/student teacher communication. It is further recommended that all aspects needed by professional educators be framed through this communication thus ensuing learning towards all aspects needed be professionals. University faculty should determine if a new form of communication should be reviewed and evaluated that more aligns with today’s students and their immersion in technology.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, 84(2),191-215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura A. (1994). Self-efficacy. in V.S. Ramachaudran (Ed.),. Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp, 71-81). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New, York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Bearman, P., McLaughlin, M., Bass, G., Pauly, E., & Zellman, G. (1977). Federal programming supporting educational change: Vol. VII. Factors affecting impimetnaiton and continuation. Santa Monica, CA:RAND. Retrived March 10, 2012 from http://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/2005/R1589.7.pdf

Berlo, D, 1960). The process of communiciaton. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston Inc.

Brown, R., & Gibson, S. (1982).Teachers’ sense of efficacy: Changes due to experience. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the California Educational Research Association, Sacramento, CA.

Connors, J. J. (1998). A regional Delphi study of the perceptions of NVATA, NASAE, and AAAE members on critical issues facing secondary agricultural education programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 39(1), 37-47.

DeMoulin, D. F. (1993). Efficacy and educational effectiveness. In J. R. Hoyle & D. M. Estes (Eds.), NCPEA: In a new voice (pp. 155-167). Lancaster, PA: Technomic Publishing Company, Inc.

Doolittle, P. E., & Camp, W. G. (1999). Constructivism: The career and technical education perspective. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 16(1), 1-21.

Dunkin, M. J., & Biddle, B. J. (1974). The study of teaching. United States of America: Holts, Rinehart, & Winston, Inc

Edgar, D.W. (2007). Structured communication: effects on teaching efficacy of teacher candidates and teacher candidate – cooperating teacher relationships. Retrieved from Texas A&M University electronic theses and dissertations collection 8548

Edgar, D. W., Roberts, T.G., & Murphy T. H. (2008). Structured communication: Effects on teacher candidate-cooperating teacher relationships. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 58(1), 94-109.

Edgar, D. W., Roberts, T. G., & Murphy, T. H. (2011). Exploring relationships between teaching efficacy and teacher candidate-cooperating teacher relationships. Journal of Agricultural Education. 52(1), 9-18

Fosnot, C. T. (1996). Constructivism: Theory, perspective, and practice. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Fritz, C. A., & Miller, G. (2003a). Supervisory practices used by teacher educators in agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(3), 34-46.

Gibson, S., & Dembo, M. H. (1984). Teachers efficacy: A construct validation. Journal of Educational Phsychology 76, 569-582.

Harms, B. M., & Knobloch, (2005). Preservice teacher’s motivation and leadership behaviors related to career choice. Career and Technical Education Research, 30(2), 101-124

Kantrovich, A. J. (2007). A national study of the supply and demand for teachers of agricultural education from 2004–2006. Grand Haven, MI: Michigan State University Extension

Kantrovich, A. J. (2010). A national study of the supply and demand for teachers of agricultural education from 2004–2006. Grand Haven, MI: Michigan State University Extension

Kasspervauer, H. J., & Roberts, T. G. (2007a). Changes in teacher candidate perceptions of the teacher candidate-cooperating teacher relationship throughout the student teaching semester. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48 (1), 31-48

Kasspervauer H.J, & Roberts, T. G.(2007b. Changes in teacher candidate perceptions of the teacher candidate—cooperating teacher relationship throughout the student teaching semester. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48 (1), 24-34.

Kershaw, I., (2008), National Council for Agricultural Education End of Year Progress Report. Retrived on June 25, 2012 from https://www.ffa.org/thecouncil/Documents/ncae2008annualreportonagriculturaleducation.pdf

Lawver, R. G., Torres, R. M. (2011). Determinats of pre-service students’ choice to teach secondary agriculture education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52,(1), 61-71

Newcomb, L. H., McCracken, J. D., & Warmbrod, J. R. (1993). Methods of teaching agriculture. Danville, IL: Interstate.

Pajares, F. (2002). Overview of social cognitive theory and of self-efficacy. Retrieved from http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/eff.html

Palmer, D. (2011). Source of efficacy information in an in-service program for elementary teachers. Wiley online library 95, 577-600

Roberts, T. G., Greiman, B. C., Murphy, T. H., Ricketts, J. C., Harlin, J. F., & Briers, G. E. (2009). Changes in teacher candidates intention to teach. Journal of Agriculture Education, 50(4), 134-145

Roberts, T.G, Harlin, J.F., & Briers, G.E. (2007). The relationship between teaching efficacy and personality type of cooperating teachers. Journal of Agriculture Education, 48(4), 55-66

Roberts, T. G., Harlin, J. F., & Ricketts, J. C. (2006). A longitudinal examination of teacher efficacy of agricultural science teacher candidates. Journal of Agricultural Education, 47(2), 81–92

Roberts, T. G., Mowen, D. L., Edgar D. W., Harlin J. F., & Briers, G. E. (2007). Relationships between personality types and teaching efficacy of teacher candidates. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(2), 92-102.

Robinson, S. R., Krysher, S., Haynes, J. C., & Edwards, M. C. (2010). How Oklahoma state university students spend their time student teaching in agricultural education: A fall versus spring semester comparison with implication for teacher education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 51(4), 142-153

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology. New York: Prentice Hall.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Classic definition and new direction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67

Schuman, L. (1996). Perspectives on instruction. Retrieved on March 8, 2012 from http://edweb.sdsu.edu/courses/edtec540/perspectives/Perspectives.html

Schunk, D. H., Pintrich, P. R., & Meece, J. L. (2008). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications. Upper Saddle, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Shoulders, C., & Myers, B. (2011). Considering professional identity to enhance agriculture teacher development. Journal of Agricultural Education. 52(4), 98-108.

Shute, V. (2007) Focus on Formative Feedback. ETS Research and Development. Retrieved on June 25,2012 from http://www.ets.org/Media/Research/pdf/RR-07-11.pdf

Stead, B. A, (1972) Berlo’s Communication Process Model as Applied to the Behavioral Theories of Maslow, Herzberg, and McGregorThe Academy of Management Journal 15( 3),389-394

Stewart, B. R. & Shinn, G. C. (1977). Concerns of the agricultural education profession: Implications for teacher education. Journal of American Association of Teacher Educators in Agriculture. 23(3), 19-26.

Strippling, C., Rickets, J. C., Roberts, T. G., & Harlin, J. F., (2008). Preservice agricultural education teachers’ sense of teaching efficacy. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(4), 120-130.

The National Council for Agricultural Education. (2002). Reinventing agricultural education for the year 2020. Retrieved from http://www.opi.state.mt.us/pdf/Agriculture/Plan.pdf

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Woolfolk Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783-805

Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk, H., A., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68, 2002-248.

Whittington, M. S., McConell, E., & Knobloch, N., A. (2006). Teacher efficacy of novice teachers in agricultural education in Ohio at the end of the school year. Journal of Agricultural Education, 47(4), 26-38.

Wolf, K. J, (2011). Agricultural Education perceived teacher self-efficacy: A descriptive study of beginning agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(2) 163- 176.

Wolf, K. J., Foster, D. D., & Birkenholz, R. J. (2010). The relationship between teacher self- efficacy and the professional development experiences of agricultural education teacher candidates. Journal of Agricultural Education, 51(4), 38-48.