Whitney L. Figland, Louisiana State University, wfigla2@lsu.edu

J. Joey Blackburn, St. Charles Community College, jblackburn@stchas.edu

Kristin S. Stair, Louisiana State University, kstair@lsu.edu

Michael F. Burnett, Louisiana State University, vocbur@lsu.edu

Abstract

One of the greatest challenges that classroom teachers face has been fostering a learning environment that caters to the needs of diverse learners. Teachers have various teaching methodologies at their disposal, ranging from passive, teacher-centered to active, student-centered strategies. The flipped classroom approach allows for teachers to become the facilitator of learning activities and students to become actively engaged in the learning experience. This transition allows for more student-centered activities to occur in class that enhance students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Team-based learning (TBL) is a modified version of flipped classroom that allows students to work collaboratively to solve complex problems. Content knowledge has long been considered an important prerequisite of higher cognitive functions such as critical thinking, problem solving, and reflective thinking. The purpose of this exploratory study was to explain the effect of cognitive style on the small gasoline engines content knowledge of undergraduate students enrolled in a flipped introductory agricultural mechanics course at Louisiana State University. To test the hypotheses, this study utilized descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation, and independent t-tests. A Mann-Whitney U test was employed to determine the influence of cognitive style on content knowledge. Overall, no differences in content knowledge were found. It is recommended to replicate this study longitudinally to increase statistical power. For practice, educators should employ learning strategies that meet the needs of students with diverse cognitive styles.

Introduction and Literature Review

One of the greatest challenges classroom teachers face has been fostering a learning environment that caters to the needs of diverse learners. To achieve this, teachers have a variety of teaching methodologies at their disposal, ranging from passive, teacher-centered methods to active, student-centered strategies (Schunk, 2012). One relatively new means of active engagement has been through the utilization of flipped classrooms. Some of the first flipped classroom models can be seen emerging into secondary and post=secondary education in the late 1990s and early 2000s after the inception of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) (Frederickson et al., 2005; Strayer, 2007; U.S. Department of Education, 2001). Baker (2000) presented his early version of the “classroom flip” as a new method of teaching that was made possible by an increase in the need for new educational methodologies that better engage learners and the increase in instructional technology availability (p. 4). Similarly, Lage et al. (2000) developed the “inverted classroom” model to invert the classroom structure and better engage students during class (p. 32). In both models, it was suggested to move instructional lecture material out of the classroom and make it available online, thus using class time for the professor to serve as a guide to assist students while providing increased time for application and practice (Baker, 2000; Lage et al., 2000). Over the past two decades, the flipped classroom approach has gained increased attention in secondary and post-secondary education for its student-centered approach and increased emphasis on engagement (Barkley, 2015; McCubbins et al., 2018).

The flipped classroom model allows teachers to become the facilitator of learning activities and the students to become actively engaged in the learning process while still focusing on delivering course content (Connor et al., 2014). This transition can allow for more student-centered activities during class to enhance students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Allen et al., 2011; Hanson, 2006). Additionally, active learning strategies promote a student-centered learning environment by creating opportunities for students to solve problems in a real-world context (Michealsen & Sweet, 2008; Sibley & Ostafichuk, 2015).

In recent years, a new type of flipped classroom has emerged as a version of a traditionally flipped classroom; team-based learning (TBL). TBL has emerged as a flipped classroom technique that allows students to work collaboratively to solve complex problems during class time (Michealsen & Sweet, 2008; Wallace et al., 2014). Similar to traditional flipped classroom models, TBL is a student-centered approach that shifts instruction away from a traditional lecture format to create a student-centered learning environment (Artz et al., 2016; Nieder et al., 2005). In a TBL-formatted course, students take on the responsibility of learning conceptual knowledge outside of class and spend more time applying that knowledge in class as a part of a team (Michaelsen et al., 2004). Essentially, TBL is formatted to provide students with opportunities to learn declarative and procedural knowledge to enhance critical thinking and problem-solving skills (Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008). One aspect of TBL that sets it apart from the traditional flipped classroom is its increased emphasis on accountability (Michaelson et al., 2004). An essential element of TBL is the administration of Individual Readiness Assurance Tests (IRATS) and Team Readiness Assurance Tests (TRATS) that serve as formative assessments after each module to ensure students have engaged with the material.

Despite the many possible applications of TBL to agricultural education, research supporting its use in agricultural education has been limited. McCubbins et al. (2016) conducted a study to examine student perceptions of TBL in an agricultural education capstone course. The findings suggested that students had a positive view of TBL and were highly satisfied with the student-centered learning environment (McCubbins et al., 2016). This study also indicated that working in teams positively impacted student motivation to learn in a collaborative setting (McCubbins et al., 2016). A similar study conducted by McCubbins et al. (2018) found that TBL in agricultural education courses supported the development of critical thinking, motivation to learn, and ability to effectively apply course concepts by undergraduate students. Focusing specifically on agricultural mechanics, a course typically heavily focused on problem solving, Figland et al. (2020a) reported that undergraduate students perceived that TBL supported the development of problem-solving skills and promoted positive collaboration between group members while increasing student self-efficacy in the content area.

The ability to increase critical thinking and problem-solving skills cannot be developed exclusively by integrating specific teaching methods. Instead, the education literature has supported the notion that the cognitive styles of students in classes and educational teams can influence the ability of students to problem solve effectively (Myers & Dyer, 2006; Parr & Edwards, 2004; Thomas, 1992; Torres & Cano, 1994; Torres & Cano, 1995; Witkin et al.,1977). Cognitive styles have typically been defined as an individual’s preferred way of organizing and retaining information to solve problems (Keefe, 1979; Kirton, 2003). The awareness of a student’s cognitive style can be an important factor in the success of their ability to solve problems (Jonassen, 2000; Witkin et al., 1977). In agricultural education, Blackburn et al. (2014) and Lamm et al. (2011) concluded that before educators can understand how to tailor lessons to teach critical thinking and problem-solving skills effectively, they must be aware of varying cognitive styles and understand how to relate those cognitive styles to successful problem solving and critical thinking development. To better understand how problem solving can be developed within agricultural education coursework, cognitive style, and innovative teaching methods can be utilized to develop students’ critical thinking ability (Figland et al., 2020b).

Theoretical Framework

Kirton’s (2003) adaptation-innovation theory (A-I theory) served as the theoretical foundation of this study to aid in furthering the understanding of how critical thinking ability can be tied to TBL teaching methodologies. A-I theory is grounded on the premise that all people are creative and can solve problems, regardless of their preferred cognitive style (Kirton, 2003). Per the theory, cognitive style is a person’s preferred way to think, learn, and solve problems (Kirton, 2003). An individual’s cognitive style is measured through Kirton’s adaption-innovation inventory (KAI). KAI scores that fall below the mean are considered more adaptive, while scores above the mean are more innovative. However, it is important to note that the scale is a continuum, and individuals are never purely adaptive or purely innovative (Kirton, 2003). In other words, two people can have scores below the mean, indicating they are more adaptive compared to the normal distribution of scores, but the individual with the higher score is considered more innovative than the other.

When comparing the more adaptive and innovative, several key distinctions exist in how these individuals prefer to learn and solve problems. More adaptive individuals prefer well-established problems and favor working within the current problem structure (Kirton et al., 1991). These individuals collaborate well with group members and generate ideas that favor consensus (Kirton, 2003). On the contrary, the more innovative prefer less structure to solve the problem and often challenge boundaries (Kirton, 2003; Lamm et al., 2012). More innovative individuals tend to stretch the boundaries of problems and generate ideas outside the current group structure (Kirton, 2003). Often, individuals falling more on the innovative side of the continuum tend to be novel and find different ways to solve problems. Whereas the more adaptive ones tend to be safer, more predictable, conforming, and less ambiguous when solving problems (Kirton, 1999, 2003).

Cognitive style is one’s preferred way of learning and engaging in problem solving tasks (Kirton, 2003). However, learners are often presented with situations in which they must learn or perform outside their preferred style. In these instances, individuals utilize coping behaviors to navigate the environment (Kirton, 2003). Often, this occurs in a setting where the person must work with individuals of diverse cognitive styles. Kirton (2003) described this as the Problem A and Problem B situations. For example, consider students assembled into a team to complete a group project. Problem A is the group assignment, while Problem B is how well the group can navigate their diverse cognitive styles to perform the task.

Little research has existed in agricultural education that investigates the effects of cognitive style on student learning outcomes in a flipped learning environment. A-I theory postulates that cognitive style is unrelated to cognitive capacity; however, little literature has been advanced in agricultural education examining this notion. Further, no literature was found that tested this hypothesis in a flipped classroom setting. As a result, the principal question that arose after reviewing the literature was: How does cognitive style effect the small gasoline engine content knowledge of undergraduate students enrolled in a flipped introductory agricultural mechanics course at Louisiana State University?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this exploratory study was to explain the effect of cognitive style on small gasoline engine content knowledge of undergraduate students enrolled in a flipped introductory agricultural mechanics course at Louisiana State University.

The following null hypotheses guided this study:

H01: There were no statistically significant differences in small gasoline engine content knowledge of undergraduate students in an introductory agricultural mechanics course based on cognitive style.

Methodology

Data associated with this study were collected as a part of a larger research project that investigated students’ abilities to solve small gasoline engine-related problems. Specifically, a one-group pretest-posttest pre-experimental design was employed to collect data for this research (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Salkind, 2010). This design is used widely in educational research when all individuals are assigned to the experimental group and observed at two points (Campbell & Stanley, 1963; Salkind, 2010). The changes from the pre-test to the post-test determine the results from the intervention; however, in this design, there is no comparison group, making it almost impossible to determine if the change would have occurred only from the intervention and not from extraneous variables (Salkind, 2010). Extraneous variables must be considered and dismissed to make any generalizations between the interventions and change (Salkind, 2010).

Population/Sample

The population of this study was all students who enrolled in an introductory agricultural mechanics course at Louisiana State University during the spring semester of 2018 (n = 17) and spring semester of 2019 (n = 15). Overall, one student in the spring semester of 2018 did not complete enough course material to be included in the study; therefore, the participating sample totaled n = 31. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was sought and granted. Per IRB, students were notified of this research on the first day of class and were given the opportunity to opt out without penalty. All students were over 18 and elected to provide signed consent to participate in this research.

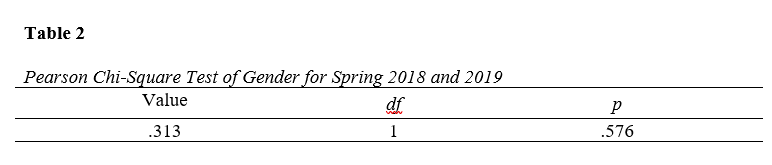

To test for homogeneity between semesters, independent sample t-tests were conducted on individual cognitive score, age, and students’ pre-course interest survey to determine if the groups were homologous. The t-test analysis found that there were not statistically significant differences between the 2018 and 2019 semesters and cognitive style (p = .109), age (p = .596), and pre-CIS (p = .062), respectively. To test for homogeneity, Levene’s test for equality of error variances was calculated and was not statistically significant; therefore, it was assumed that the variances were almost equal and the groups were similar.

Further, a Chi-Square test was employed to determine if differences existed between the two semesters based on gender (X2 = .313, df = 1, p = .576). Therefore, from the analysis, it is concluded that our population from both semesters was homologous, and subsequently, the data were merged for further data analysis.

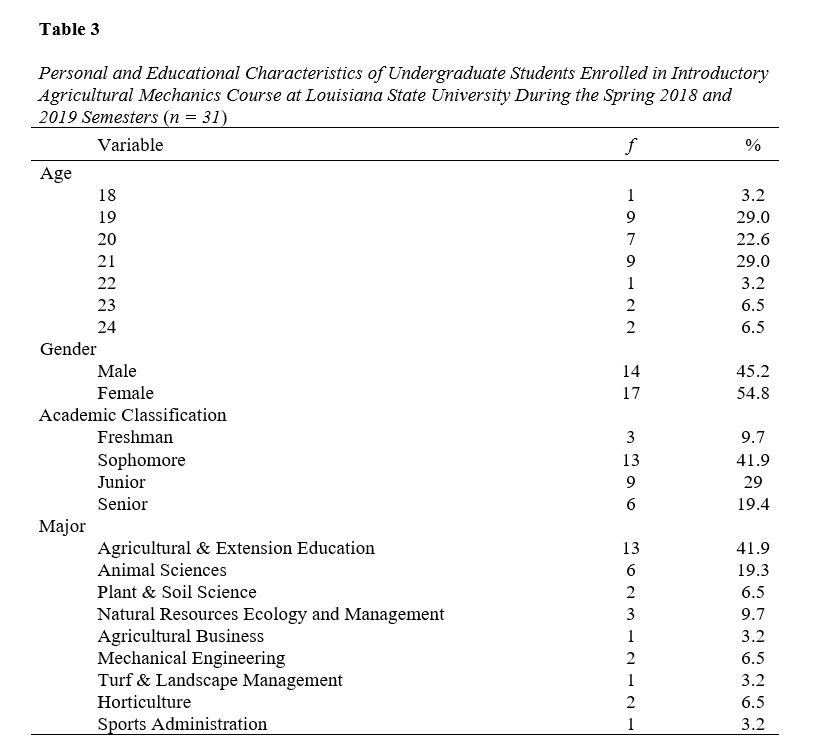

While the course was offered through the Department of Agricultural and Extension Education and Evaluation at Louisiana State University, it was advertised throughout the college and university. Table one provides the personal and educational characteristics of students (n = 31) who enrolled in this course during the spring of 2018 or 2019. Overall, these students’ ages ranged from 18 to 24, with 19 (29.0%) and 21(29.0%) being the most reported ages. The majority (n = 17; 54.8%) of students were female, and sophomore (41.9%) was the most frequently reported academic classification. In all, nine majors were represented in this course, with Agricultural and Extension Education being the most common (41.9%).

Instrumentation

Kirton’s adaptation-innovation inventory (KAI) was used to determine students’ cognitive styles (Kirton, 2003). This instrument consisted of 32 items that asked questions about the individuals’ preferred way to learn. The KAI scores range from 32 to 160 on a continuum from more adaptive to more innovative, with a theoretical mean of 96 (Kirton, 2003). However, the practical mean of the KAI is 95 (Kirton, 2003). Therefore, individuals who score 95 or below are considered more adaptive, while those who score 96 or above are considered more innovative. The instrument has been successfully utilized to determine the cognitive style of a wide variety of individuals from varying backgrounds (Kirton, 2003). Internal reliability of this instrument has been measured through multiple studies. Kirton (2003) reported that after analyzing data from six different population samples with over 2,500 respondents that internal reliability coefficients ranged from .84 − .89. Also, 25 other studies that utilized the KAI showed reliabilities between .83 and .91 (Kirton, 2003).

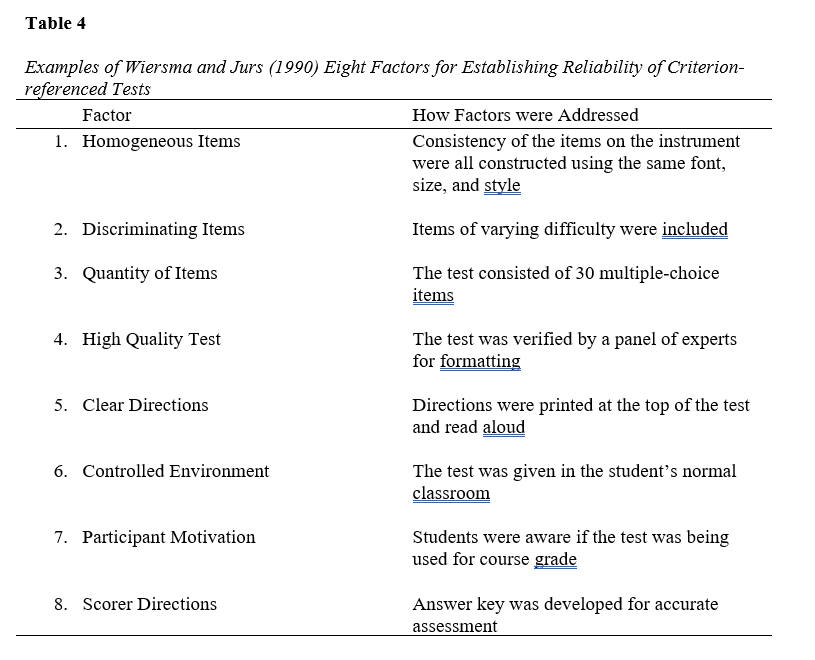

Due to the nature of this pre-experimental study, it was important to determine the students’ knowledge in small gasoline engine content before and after the intervention. The researcher developed a 30-item criterion-referenced test to test the individual’s knowledge. It should be noted that half of the questions on this test were developed by Blackburn (2013) and further modified to meet the needs of this study. The other 15 questions were developed by the researcher based on the Small Engine Care & Repair textbook written by London (2003), a Small Engines Equipment and Maintenance textbook written by Radcliff (2016), and the Briggs and Stratton PowerPortal website. The criterion-referenced test was formatted using a four-option multiple-choice template, including one correct answer and three distractors. Guidelines offered by Wiersma and Jurs (1990) were followed to ensure the reliability of the criterion-referenced test. Table two provides the factors considered as well as how each was addressed.

Course Structure and Procedures

On the first day of the small gasoline engines unit, the KAI and the 30-item pretest were administered to the students. Due to using TBL as the primary teaching strategy, the students were grouped purposively by cognitive style into teams in which they would remain for the duration of the unit. Teams were developed as heterogeneous, homogeneous adaptive, or homogenous innovative. The course layout was formatted based on Michealsen and Sweet’s (2008) recommendations.

In the small gasoline foci, five individual modules were constructed, including (a) small engine tool and part ID, (b) 4-cycle theory and fuel, (c) ignition and governor systems, (d) cooling/lubrication system, and (f) troubleshooting. After each module, students completed an IRAT to determine their content knowledge retained. After completing the IRAT, the students would join their assigned team and complete the TRAT. During the TRATs, students were allowed to collaborate with other members to come to an agreement on items they may have gotten incorrect. The goal of completing the IRAT before the TRAT was to ensure that all group members of the team contributed equally. At the end of the small gasoline engine unit, the 30-item criterion-referenced test was administered.

Data Analysis

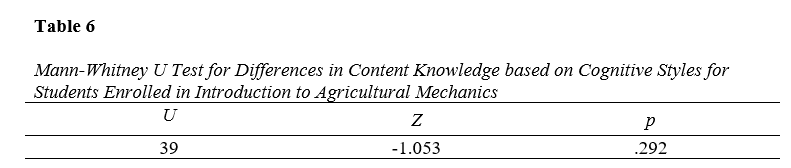

Descriptive statistics were utilized to test this study’s hypotheses, including means and standard deviations and independent sample t-tests. Independent sample t-tests are utilized to compare the means of two independent groups and determine if they are statistically significant. In this study, the t-tests were utilized to determine if the groups from the 2018 and 2019 semesters were homologous and could be merged for further data analysis. Further, Mann-Whitney U tests were employed to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between content knowledge and cognitive style.

Findings

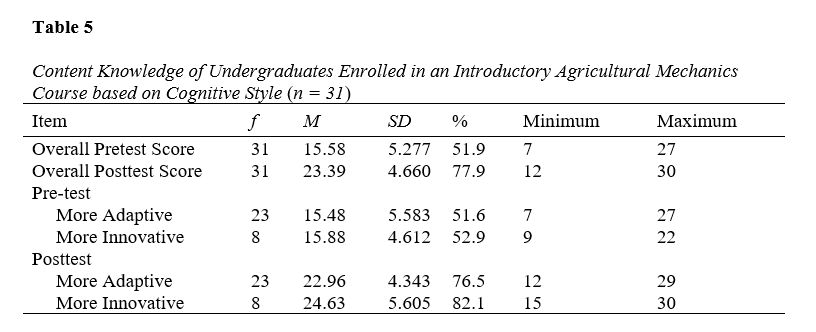

The overall mean of the pretest was 15.58 (51.9%). The mean of the more adaptive students pretest was 15.48 (51.6%), while the more innovative averaged 15.88 (52.9%). Regarding the post-test, the overall mean was 23.39 (77.9%). The more adaptive students’ average score was 22.96 (76.5%), and the mean post-test score of the more innovative students was 24.63 (82.1%), as presented in Table 5.

A Mann-Whitney U test was employed to determine if a statistically significant difference in content knowledge existed based on cognitive style. This test (see Table 6)determined no statistically significant differences in content knowledge by cognitive style (p = .292) at the .05 level.

Conclusion and Limitations

Overall, the statistical analysis revealed that cognitive style did not affect the small gasoline engine content knowledge of students enrolled in an introductory agricultural mechanics course at Louisiana State University. Therefore, the researchers failed to reject the null hypothesis. This conclusion aligns with the A-I theory in that cognitive style does not relate to cognitive capacity. In other words, one’s preferred style or manner of learning and problem solving does not influence the ability to learn or performance. Similarly, this research aligns with the findings of prior research that investigated factors influencing content knowledge achievement (Blackburn, 2013, 2014; Pate et al., 2004). However, these prior studies did not include a pretest measure of small gasoline engine content knowledge; therefore, they failed to account for pretreatment differences in content knowledge. Further, research should be conducted to compare the TBL method of teaching small gasoline engine content with direct instruction. Due to the lack of a comparison group, it is not known whether students in these semesters would have performed better or worse than similar students taught in a more traditional format. This type of research could allow practitioners greater confidence that, at a minimum, they are not impeding students learning by employing TBL in their classrooms.

This study was conducted during two spring semesters to increase the sample size to enhance statistical power. However, due to enrollment sizes and data attrition, the overall sample was only 31 students. Small sample sizes are a detriment to most parametric statistical tools; however, these data were tested for normality in SPSS. However, due to the low sample size, the statistical power of this research was inherently low, which increased the chance of committing Type-II errors.

An additional limitation of this study was the lack of random selection of participants. Due to the nature of using student enrollment in a particular class, caution must be given when interpreting the findings, and it cannot be generalized past the sample reported in this research. The introductory agricultural mechanics course was required for students majoring in agricultural and extension education and has become an increasingly popular elective for other majors across the university. Students not required to complete this course may have a higher mechanical aptitude or prior knowledge and/or experiences in the content areas, which may influence their performance in the course.

Recommendations

To increase statistical power, it is recommended that this research be extended for a minimum of three more semesters. Depending on enrollments, this would increase the sample size to more than 75 students. A sample size of 75 to 100 would sufficiently increase power. Further, additional variables such as mechanical aptitude should be assessed to determine the impact on content knowledge. Additionally, content knowledge should be utilized as an independent variable to determine its role in students’ problem-solving ability in authentic learning environments. Additional research should determine the effect of these diverse cognitive teams on the ability to generate hypotheses and solve authentic problems. Content knowledge could also be employed in a multiple regression model to determine its impact when hypothesizing and solving contextual problems.

Practitioners should be informed that cognitive styles influence how students prefer to learn and solve problems (Kirton, 2003) but are not related to how well a student learns. Teachers should strive to create learning environments conducive to diverse learners to ensure all students have an opportunity to learn (Roberts et al., 2020). As teachers provide opportunities for diverse learning styles – auditory, kinesthetic, and visual – they should provide opportunities geared toward the more adaptive and innovative problem-solving styles. This would ensure one style preference is not constantly required to employ coping behaviors to succeed. Post-secondary educators should consider TBL if they are interested in flipping an agricultural mechanics course. Results from this study indicated that, based on cognitive style, all students can learn successfully. Further, the use of frequent IRATs and TRATs ensures a level of accountability not normally found in traditional flipped classes.

References

Allen, D. E., Donham, R. S., & Bernhardt, S. A. (2011). Problem-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(128), 21−29. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.465

Artz, G. M., Jacobs, K. L., & Boessen, C. R. (2016). The whole is greater than the sum: An empirical analysis of the effect of team based learning on student achievement. NACTA Journal, 60(4), 405−411. http://www.nactateachers.org/index

Baker, J. W. (2000). The “classroom flip”: Using web course management tools to become the guide by the side. Communication Faculty Publications.

https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/media_and_applied_communications_publications/15

Barkley, A. (2015). Flipping the college classroom for enhanced student learning. NACTA Journal, 59(3), 240−244. https://www.nactateachers.org/attachments/article/2312/16%20%20Barkley_Sept2015%20NACTA%20Journal-10.pdf

Blackburn, J. J. (2013). Assessing the effects of cognitive style, hypothesis generation, and the problem complexity on the problem solving ability of school-based agricultural education students: An experimental study (Doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University). https://www.proquest.com/docview/1427918810?pqorigsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

Blackburn, J. J., Robinson, S. J., & Lamm, A. J. (2014). How cognitive style and problem complexity affect preservice agricultural education teachers abilities to solve problems in agricultural mechanics. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(4), 133−147. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2014.04133

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Houghton.

Conner, N. W., Stripling, C. T., Blythe, J. M., Roberts, T. G., & Stedman, N. L. P. (2014). Flipping an agricultural education teaching methods course. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(2), 66−78. https://doi.org10.5032/jae.2014.02066

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage publications.

Figland, W. L., Blackburn, J. J., & Roberts, R. (2020a). Undergraduate students’ perceptions of team-based learning during an introductory agricultural mechanics course: A mixed methods study. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(1), 262-276. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.01262

Figland, W. L., Roberts, R., &Blackburn, J. J. (2020b). Reconceptualizing problem solving: Applications for the delivery of agricultural education’s comprehensive, three-circle model in the 21stCentury. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 70(1), 1-20. http://jsaer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/70-Figland-Roberts-Blackburn.pdf

Frederickson, N., Reed, P., & Clifford, V. (2005). Evaluating web-supported learning versus lecture-based teaching: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning, 50(4), 645−664. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/64947/

Hanson, D. M. (2006). Instructor’s guide to process-oriented guided – inquiry learning. Pacific Crest.

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology: Research and Development, 48(4), 63−85. http://link.springer.come/article/10.007%2FBF02300500LI=true#page-1

Keefe, J. W. (1979). Learning style: An overview. In Keefe, J. W. (Ed.), Student learning styles: Diagnosing and prescribing programs, (pp.1−17). National Association of Secondary Principals. https://eduq.info/xmlui/handle/11515/10081

Kirton, M. J. (1999). Kirton adaption-innovation inventory feedback booklet. Occupational Research Center.

Kirton, M. J. (2003). Adaption-innovation: In the context of diversity and change. Routlage.

Kirton, M., Bailey, A., & Glendinning, W. (1991). Adaptors and innovators: Preference for educational procedures. The Journal of Psychology, 125(4), 445-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1991.10543307

Lage, M., Platt, G., & Treglia, M. (2000). Inverting the classroom: A gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. Journal of Economic Education, 31(1), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183338

Lamm, A. J., Rhoades, E. B., Irani, T. A., Roberts, T. G., Snyder, L. J., & Brendemuhl, J. (2011). Utilizing natural cognitive tendencies to enhance agricultural education programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(2), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2011.02012

Lamm, A. J., Shoulders, C., Roberts, T. G., Irani, T. A., Unruh, L. J., & Brendemuhl, J. (2012). The influence of cognitive diversity on group problem solving strategy. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.01018

London, D. (2003). Small engine care & repair: A step-by-step guide to maintaining your small engine. Creative Publishing International.

McCubbins, O. P., Paulsen, T. H., & Anderson, R. G. (2016). Student perceptions concerning their experience in a flipped undergraduate capstone course. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(3), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.03070

McCubbins, O. P., Paulsen, T. H., & Anderson, R. (2018). Student engagement in a team-based capstone course: A comparison of what students do and what instructors value. Journal of Research in Technical Careers, 2(1), 8−21. https://doi.org10.9741/2578-2118.1029

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (2004). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team‐based learning. New directions for teaching and learning, 2008(116), 7−27. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.330

Myers, B. E., & Dyer, J. E. (2006). The influence of student learning style on critical thinking skill. Journal of Agricultural Education, 47(1), 43−52. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2006.01043

Nieder, G. L., Parmelee, D. X., Stolfi, A., & Hudes, P. D. (2005). Team-based learning in a medical gross anatomy and embryology course. Clinical Anatomy, 18(1), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.20040

Parr, B., & Edwards, M. C. (2004). Inquiry-based instruction in secondary agricultural education: Problem-solving-An old friend revisited. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(4), 106-117. https://doi.org10.5032/jae.2004.04106

Pate, M. L., Wardlow, G. W., & Johnson, D. M. (2004). Effects of thinking aloud pair problem solving on the troubleshooting performance of undergraduate agriculture students in a power technology course. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2004.04001

Radcliff, B. R. (2016). Small engines. American Technical Publishers.

Roberts, R.,& Stair, K. S., Granberry, T. (2020). Images from the trenches: A visual narrative of the concerns of preservice agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(2), 324-338. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.02324

Salkind, N. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. Sage.

Schunk, D. H. (2012). Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed.). Pearson.

Sibley, J., & Ostafichuk, P. (2015). Getting started with team-based learning. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Strayer, J. (2007). The effects of the classroom flip on the learning environment: A comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a flip classroom that used an intelligent tutoring system (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University). http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1189523914

Thomas, R. G. (1992). Cognitive theory-based teaching and learning in vocational education.Eric Clearinghouse on Adult Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED345109

Torres, R. M., & Cano, J. (1994). Learning styles of students in a college of agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 35(4), 61−66. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1994.04061

Torres, R. M., & Cano, J. (1995). Examining cognition levels of students enrolled in a college of agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 36(1), 46−54. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1995.01046

U.S. Department of Education. (2001). The condition of education 2001. Author. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2001/2001072.pdf

Wallace, M. L., Walker, J. D., Braseby, A. M., & Sweet, M. S. (2014). “Now, what happens during class?” Using team-based learning to optimize the role of expertise within the flipped classroom. Journal of Excellence in College Teaching, 25(3), 253−273. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1041367

Wiersma, W. & Jurs, S.G. (1990). Educational measurement and testing (2nd ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

Witkin, H. A., Moore, C. A., Goodenough, D. R., & Cox, P. W. (1977). Field-dependent and field-independent cognitive styles and their educational implications. Review of Educational Research, 47(1), 1−64. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.3102/00346543047001001