Authors

Damilola Ajayi, University of Florida, d.ajayi@ufl.edu

Kathleen D. Kelsey, University of Florida, kathleen.kelsey@ufl.edu

Abstract

Collaboration among land-grant university faculty, staff, and stakeholders is crucial to addressing complex issues that defy solutions through individual efforts. The need for sustainable management practices that are environmentally friendly to mitigate activities of pests on growers’ farms, as well as enhance agricultural production, in the face of rapidly expanding global population, climate change, and increasing food demand is of utmost importance. Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) emerged in the U.S. as an invasive pest in 2008. It is a daunting pest that destroy berry and cherry crops globally. Marketers have a zero-tolerance policy for SWD in fruit and are declared a total loss at market. Over the past 15 years, a multi-institutional, multi-disciplinary land-grant university team has created and disseminated a variety of mitigation strategies to growers. This study identified factors underpinning the successful outcomes of the collaborative team using single case study design. Eighteen researchers were involved in the project, 12 agreed to participate in the study. Data collected through interviews, participant observations, and documents were inductively and deductively coded to explore the variables responsible for the unusually long-term collaboration. Participants described their experiences as professional, productive, and expertise based. Factors that positively impacted the team’s high production record included their ability to collaborate, the nature of the problem (invasive pest protocols), team expertise, professional relationships, respect for others, openness, effective communication, positive personality, support for one another, division of labor, and choice/flexibility to join various research projects. The use of improved communication tools and data-sharing software were recommended to further improve transparency and productivity.

Introduction

Land-grant university researchers, Extension specialists, and growers have been collaborating to mitigate agricultural and nutritional challenges in the U.S. for over 160 years with great success using the historical research and Extension model that evolved from the Morrill Act of 1862 (Seevers et al., 1997). The need for environmentally sound practices that promote sustainable, efficient, and enhanced agricultural production and nutritional best practices to meet the increasing demands for food and industrial raw materials globally has continued to benefit from this model and is thriving under the leadership of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and funding from the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), among other sources.

Researchers, Extension specialists, growers, government, and non-profit organizations collaborate to solve complex agricultural and socio-ecological challenges that defy individual efforts (Bodin, 2017). Active collaboration among diverse teams have been a foundational principle for addressing complex problems such as environmental management (Eaton et al., 2022), growers’ health and safety needs (Reed et al., 2021), energy conservation on farms, crop and animal production, and pest control (Macknick et al., 2022; Worley et al., 2021). The emergency response from land-grant university researchers to the destructive activities of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) (SWD), a devastating invasive pest of berry and cherry crops (Sial et al., 2020), bolstered the need for scientific collaboration across the U.S. and globally. Limited information exists on social factors responsible for long-term scientific collaborations for tackling invasive pests. Therefore, there is a need to explore the factors responsible for sustaining long-term collaborations that hold the potential to mitigate the SWD infestation in the U.S.

Theoretical Framework

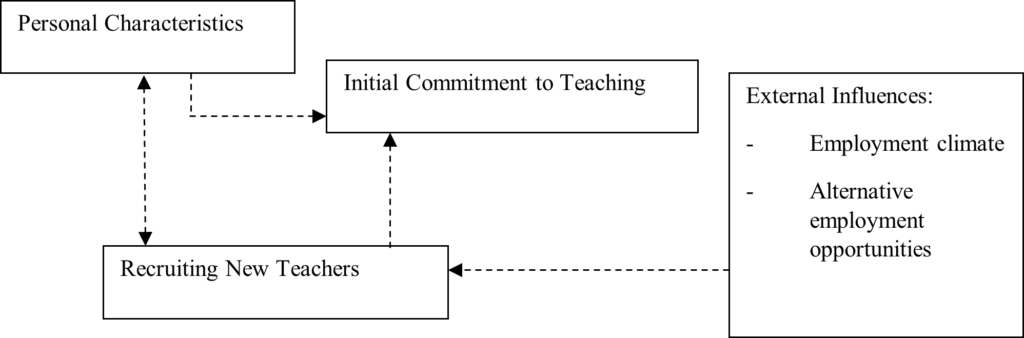

Social constructivism defines learning as a deliberate social practice involving the negotiation of shared knowledge among actors, resulting in a shared understanding of reality. (Bruner, 1966; Dolittle & Camp, 1999; Gasper, 1999; Kant et al., 1934). According to Akpan et al. (2020), social constructivism draws on collaboration for effective learning. In this single case study, we applied Gray’s (1989) theory of collaboration to explore the factors responsible for the long-term collaboration between land-grant university researchers and stakeholders in proffering sustainable management practices for SWD in the U.S. Gray explained that collaboration as “a joint decision-making process among key stakeholders of a problem domain about the future of that domain” (1989, p. 227). Ankrah and Omar (2015) and Bekkers and Bodas (2008) expanded this definition to include cooperation, interaction, and relationships between individuals in social settings or organizations that are targeted at enhancing knowledge sharing or information transfer.

Agriculture by nature faces intricate social, environmental, and agronomic challenges. This has prompted Extension programming and agricultural education to develop collaborative strategies focused on identifying specific issues affecting the environment, conveying such information to land-grant researchers, stimulating the formation of interdisciplinary teams of researchers to address them, and organizing educational programs to reach growers through Extension services (Blanco, 2020; Sulandjari et al., 2022; Coutts et al., 2017; Velten et al., 2021).

Collegiality among researchers has also been identified as a critical factor that enhances scientific research collaborations and productivity (Marlows & Nass-Fukai, 2000) via trustworthy connections as individuals are recognized as equals and for their distinctive contribution to the team (Thorgensen & Mars, 2021). Collegiality facilitates learning and professional development among collaborators (Kelly & Cherkowski, 2015; Rensfeldt et al., 2018). Long-term interdisciplinary collaboration among agricultural researchers from various institutions and Extension professionals has been shown to foster the social construction of agricultural knowledge, solve complex problems, and advance research in dynamic environments beyond the reach of individual efforts. Collaboration extends to growers, facilitating necessary changes in agricultural practices (Díaz, 2021; Pham & Tanner, 2015).

Some of the benefits arising from long-term scientific research collaboration include connecting experts across geographically diverse research communities, who bring differing global perspectives to manage complex challenges, provide problem solving skills to growers and advance agricultural practices and development (Arnal, 2018; Sulandjari et al., 2022). Other desirable social benefits are enhanced understanding, co-innovation, co-authorship, interactive learning, public-private partnerships, public diffusion of results, commercialization of research products, and profit maximization. Individual benefits include self -reflection, increased academic funding and publications, research advancement, reduction in orientation barriers among universities, and trust building among collaborators (Arsenyan et al., 2015; Bekkers & Bodas-Freitas, 2008; Bekkers & Bodas-Freitas, 2011; Brown et al. 2021; Cantner et al., 2017; Cronin et al, 2003; Duta & Martinez-Rivera, 2015; Geissdoerfer et al., 2018; Li, 2015; Skelcher et al., 2013; Storksdieck et al., 2016; Tartari et al., 2012; van der Wal et al., 2021; Wuchty et al., 2007).

Despite wide adoption of collaboration and its significance in various fields, challenges to collaboration include power sharing, consensus building, diverse stakeholder needs, higher trade-offs compared to joint gains (Margerum & Robinson, 2016), deep-seated cultural and regional bias and language (Hill et al., 2012; Schubert & Glanzel, 2006), conflicts (Margerum & Robinson, 2016), non-representativeness of stakeholder views (Purdy, 2012), and legal and regulatory policies among collaborating institutions (Jeong et al., 2011). Regardless of barriers, collaboration among individuals, organizations, and institutions continues to rise as the benefits far outweigh the limitations (Abramo et al., 2013). Dossou-Kpanou et al. (2020) and Paphawasit and Wudhikarn (2022) observed that an important factor that enhanced collaboration was formal and informal communication that engenders trust, familiarity, cooperation, and connectedness. It follows that for an innovation to be developed and adopted, there must be effective communication (Foray & Steinmueller, 2003; Rogers, 2003). Agricultural education and Extension play a crucial role in communicating innovations by incorporating research findings into the literature and developing curricula to reach a broad audience (Ikendi et al., 2023).

Purpose

The purpose of the single case study was to explore the factors responsible for building an enduring collaborative team by describing participants’ experiences as members of a long-term scientific collaboration focused on mitigating SWD infestation in the U.S. Specifically, this study sought to answer the following research questions:

- What were participants’ roles within the collaborative team?

- What factors contributed to building collegiality?

- What factors contributed to the long-term sustainability of the team?

- What were the benefits of the collaboration over time?

- What challenges did the participants face in establishing a resilient team?

- How did participants experience communication within the team?

Methods

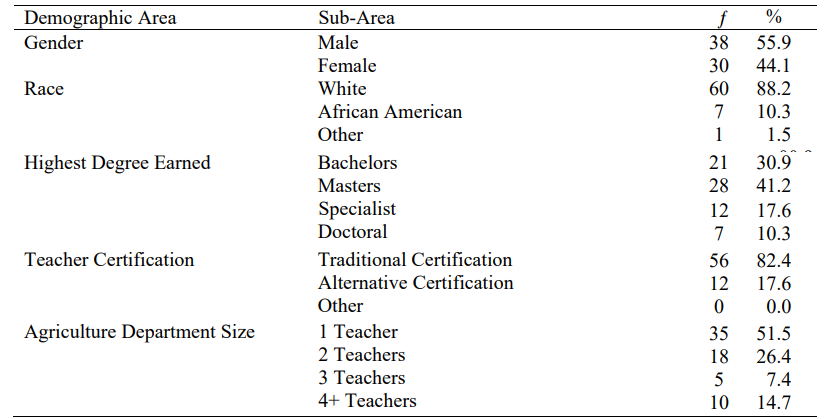

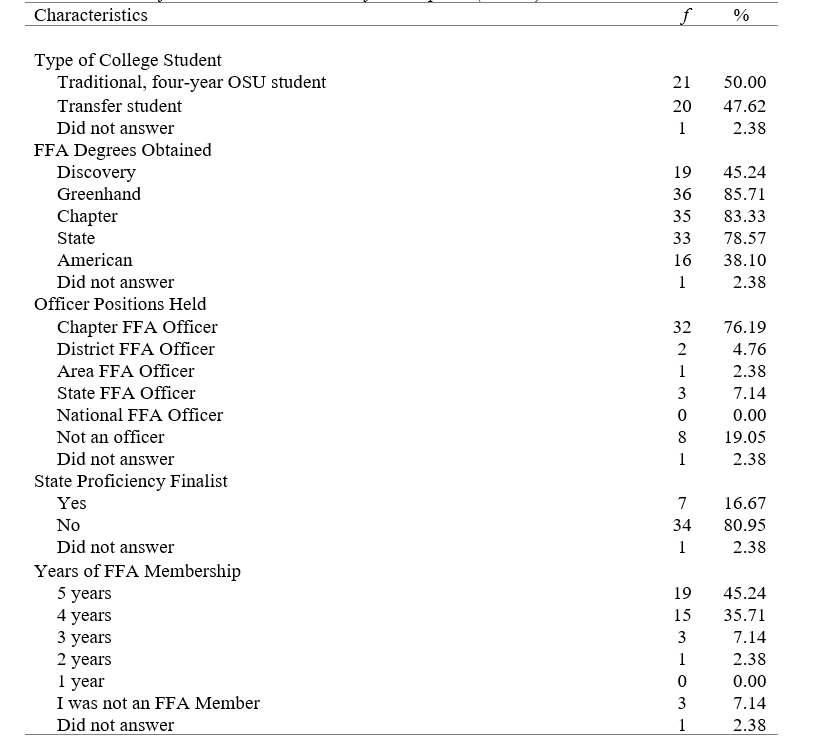

We employed a single case study design to answer the research purpose. This approach focuses on gaining an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon under real-life contextual conditions using multiple units of analysis (Yin, 2003). This design is suitable for program evaluation and groups within organizations or agencies (Creswell, 2007). The design was best suited for this study because our case represents a unique long-term collaboration among land-grant universities researchers and was bounded by people, place, and time. Eighteen researchers were involved in the collaboration, 12 agreed to participate in the study, ten of which were entomologists and two were economists. Nine identified as male and three as female. Six worked in the Northeast U.S., three worked in the Southwest, two worked in the Southeast and one worked in the Northwest. The average experience of the researchers was 10 years, and they had at least three junior researchers working in their laboratories. Participants were experts in the fields of economics and entomology and represented 10 states with SWD infestation. In presenting the data we used pseudonyms to ensure participant’s confidentiality (Creswell, 2013) (see Table 1).

Validity was enhanced using multiple sources of data, which also served to triangulate findings and provide rich descriptions (Creswell, 2013; Yin, 2003). We collected data by (a) observing the team through monthly meetings over an eight-year period; (b) analyzing documents and research protocols produced; and (c) conducting in-depth interviews with the participants, which lasted between 55 to 75 minutes (McLeod-Morin et al., 2020). The interview data were recorded, transcribed, cleaned, and then sent to the participants for member checking to ensure validity and trustworthiness (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

After feedback was received from the participants, we used ATLAS.ti 22® software for Windows® to analyze the data within the context of the case (Lamm & Carter, 2019). Data were inductively and deductively coded to identify phrases that were consistently mentioned as emergent themes and in alignment with theory and emerging themes. Interview data were independently coded by investigators and codes were compared to achieve inter-rater reliability and thematic credibility (Saldaña & Omasta, 2020). These were later triangulated with observation and document data (Wright et al., 2021; Yin, 2003). Observation notes and artifacts were used to triangulate interview findings. Data saturation was achieved when there were no new revelations in the data. Credibility was established through multiple data sources (Yin, 2003) including peer debriefing to ensure our conclusions were consistent with participants’ lived experiences (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008; Merriam, 1988).

To minimize biases (Creswell, 2013), reflexivity was achieved by reporting our background as a Ph.D. student and professor in the department of Agricultural Education and Communication. We engaged monthly with the SWD team and acted as participant observers in the capacity of external evaluators. Memos were kept all through the data collection and analysis process for bracketing purposes to ensure internal reliability and highlighting salient themes (Saldaña & Omasta, 2020). Our findings are part of a larger study conducted over eight years. Due to the qualitative nature of this study and the small population involved, findings may not be generalizable beyond this context. Furthermore, the population is limited to interdisciplinary agricultural researchers from land-grant universities in the U.S. We assumed that the participants gave honest answers to the questions and were actively involved in collaborative efforts for approximately 15 years. Abundant evidence confirms these assertations.

Results

Q1. What Were Participants Roles within the Collaborative Team?

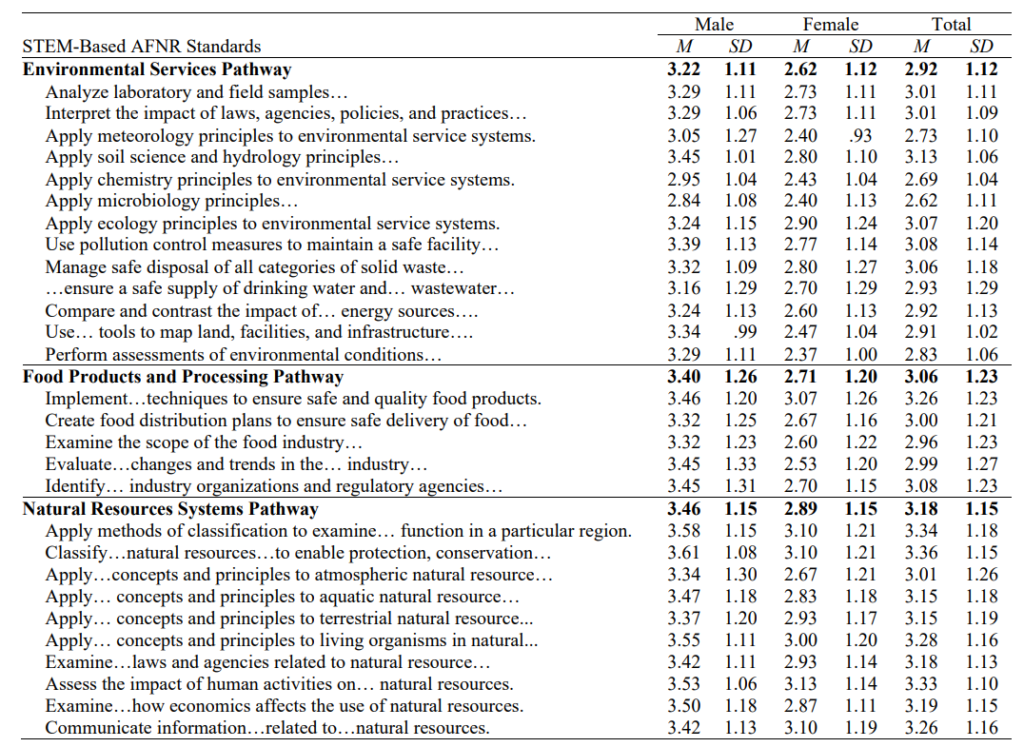

We found that the team consisted of researchers with diverse professional backgrounds, experiences, distinct roles, and responsibilities who intentionally contributed their assets and joined forces to achieve optimal outputs nationwide as displayed in Table 1. Seven participants acted in several research capacities within the collaborative team. They played different and sometimes multiple strategic roles within the team. For example, William and Jason helped to secure permits for field releases of a parasitic wasp from governmental agencies for all the collaborators, bred and raised mass beneficial parasitoids, trained laboratory assistants in other states on the rearing procedures, and distributed parasitoids to five collaborators (Caleb, Daniel, Charles, Anthony and Noah) for field release.

James, the leader of the national research team, explained that “the project was organized by objectives, with at least two researchers leading each objective.” He collaborated with Grace and they both “worked directly with berry and cherry grower/influencers to implement what we know to economic aspects, to behavioral and biological control, chemical control and resistance management aspects of this project.” Grace corroborated James’ explanation stating that she “actively built the research and Extension program in N.E., specifically working blackberry and some blueberry growers and also leading objective one, which was coordinating grower engagement throughout the country.”

According to, William his “role on this project was to investigate natural enemies of SWD and then participate and co-lead the foreign exploration for new natural enemies. This lab was primarily responsible for securing the USDA APHIS permit to get this important beneficial insect through the USDA APHIS and North American Plant Organization to get permits to release Ganaspis brasiliensis as planned releases for states as a form of classic bio control.”

There was clear evidence that the research team was composed of diverse professionals with significant expertise. They were very productive in addressing the complicated challenges imposed by SWD. Furthermore, the team allocated sufficient time to individuals to provide updates on their work, discuss the research protocols, share approval permits, and discuss challenges.

Table 1

Demographic Characteristics of the Population

| Name | Gender | Specialization | Region | Years Collaboration |

| James, PI | Male | Entomology | SE | 12 |

| Grace | Female | Entomology | SE | 12 |

| Caleb | Male | Entomology | SW | 14 |

| Eva | Female | Molecular biologist | SW | 10 |

| Jason | Male | Entomology | SW | 10 |

| Charles | Male | Entomology | NE | 12 |

| Daniel | Male | Entomology | NE | 6 |

| Emmanuel | Lead | Economics | NE | 7 |

| Noah | Male | Entomology | NE | 12 |

| Anthony | Male | Entomology | NE | 10 |

| William | Male | Entomology/ Biologist | NE | 6 |

| Olivia | Female | Economics | NW | 7 |

Note. Southeast (SE), Southwest (SW), Northeast (NE), Northwest (NW).

Q2. Were Team Members Collaborative, If So, What Factors Contributed to Building Collegiality?

This dataset resulted in three themes to explain factors underlying collegiality and productivity. There were (a) nature and distribution of the problem; (b) need for expertise; and (c) quest for knowledge.

Theme 1: Nature and Distribution of the Problem

We found that the research team was exceptionally collaborative and relied on each other’s expertise and social networks to build collegiality. When asked about the factors contributing to team building, James stated “We faced a problem that crosses state boundaries… which no one person or one team could address… we needed to engage as many states, co-principal investigators, and laboratories as possible, to investigate multiple aspects of this project and to develop a program that is appropriate, not only for one region but multiple regions because this is an across the board problem for berry and cherry crops and the pest (SWD) needs different strategies specific to each crop and environment.” This corroborates the response given by Anthony, who stated that “due to the distribution of the pest across the U.S., there was need for concerted efforts which facilitated collegiality.”

Theme 2: Need for Expertise

Each collaborator identified various roles to assume within the greater whole to address the grand challenge. For example, Noah identified the need for testing different technologies in different states under different conditions, Jason and William reported that their focus was on gaining access to biological agents from other collaborators in Europe, South Korea, and Southern China as well as obtaining permits from government authorities for parasitoid rearing and distribution to U.S. laboratories, and its eventual release in the field. Emmanuel and Olivia reported that “the need for economic insight on the implementation of the research technologies in the eastern and western U.S. necessitated their contributions to building the collaboration.” This was also supported by James who stated that “Emmanuel and Olivia were leading economic analysis, and everybody is participating with them to evaluate economic aspects of the different IP strategies that we are developing.” From Eva’s perspective, “the need for genomics analysis to identify insecticide resistance in SWD across the nation” facilitated collegiality among members.

Theme 3: Quest for Knowledge

Leveraging fundamental knowledge from the first academic laboratory where the research began upon the detection of the pest in the U.S. and the need to learn more about what’s going on around the country were cited as major reasons for collegiality in the team. According to Caleb, “our lab was the first academic lab to work with SWD, because it was found here in California originally when it was first found in United States in 2008. And so, we worked with that before we even knew what species SWD was and so the initial work was just trying to control it any way [possible].” This statement was reinforced by Charles, who reported that “working with scientists that started the work plus personal interest in knowing current research trends and needs” facilitated collegiality. Further, Daniel explained that the “need to expand the research beyond high to wild blueberry, which is different from other types of berries produced in other states” was a contributory factor to the team’s collegiality.

Q3. What Factors Contributed to the Long-Term Sustainability of the Team?

Six themes emerged to describe factors associated with the sustained relationships of the team

Theme 1: Collaboration with Good People

Anthony, who worked with the team for 10 years, described the team as a “good, collaborative, and productive team. We support each other. It’s a great team of people to work with and that is why I have continued with this team for so many years.” Emmanuel explained that working with the group was “quite worth it and is excellent. I couldn’t work in a nicer group environment; they are they are wonderful. I have learned a lot from them. I wish I could have more contact with all of them.” William also reported that “we have some good people on board, … they have been very effective and efficient.” Similarly, Olivia stated that “the folks on the grant have been really helpful if, for example, Charles has helped me very intensely in seeking growers’ contacts and pest consultants and Caleb has directed me to the right people to start asking questions for pest consultants.”

Theme 2: Professionalism

Professionalism was demonstrated by the team of researchers. Caleb and Grace stated that integrity, good personality, respect for each other, willingness to learn and researcher expertise were instrumental to the success of the team. In Charles words “They are genuinely invested in solving problems, they share, and all that and I think we’re all for the most part, motivated by that.”Other factors identified by William, Daniel, and Eva included pre-existing student-advisor relationships, which evolved into collegial relationships and support as students moved into faculty roles.

Theme 3: Capacity Development and Networking

Career development was an important factor that contributed to the team’s long sustainability Daniel identified “prospects for career development as a researcher and the opportunity to work with good people as factors that have contributed to the team’s sustainability over the years.” Noah also explained that “one thing that the project does is that it helps you to be involved with a big network of researchers…. Charles and Daniel are coming to visit us …, because they are going to get Ganaspis and they are going to stop by on their way, and I am going to meet them…it is like networking for early career.” Grace stated that the research and professional relationships that existed had “exposed young researchers to multiple and different research teams around the country. And that’s been really beneficial for them as they move on in their careers” Olivia reported that “the bolus of this project is that I was able to connect with different pesticide consultants in the state of Washington and they were able to collect data on what programs or strategies to control for different pests and diseases for blueberries and sweet cherries in the Pacific Northwest including obviously, Spotted Winged Drosophila.”

Theme 4: Communication

Frequent communication was found to be a strong factor for the sustained collaboration in this study. All 12 of the participants reported that good communication among team members and well-structured regular meetings were instrumental to the sustained collaboration. From our observations, a monthly general meeting was held to discuss team progress while sub-teams meet independently to advance their research efforts. In addition, participants communicated through email.

Theme 5: Synergy and Cohesion

Emmanuel and Noah stated that he was motivated by the intelligence of team members, commitment to the work, good understanding of research activities, flow and openness of the team to new research ideas, transparent activities, team spirit, less competition, and freedom to select areas of research interests. This was corroborated with our observations as scientists demonstrated good understanding of their roles and asked for clarifications from other researchers working on a specialized aspect of the research. There was unity within the team with few incidences of tension, conflict or strife. We observed that the team was composed of mature minds who were interested in solving problems rather than pursuing individual interests.

Theme 6: Leadership

Eleven participants reported that strong leadership, excellent team coordination, and regularly scheduled meetings were influential factors contributing to long-term sustainability of the team. According to Charles “I think a lot of that comes from the leadership. The leader has been good at getting us on regular meetings to talk about all the pieces of the project. So, I think just his regular organization of those meetings has really helped. We also have sub-objectives, and objective meetings through the year and that’s been good for keeping in contact with people.”

Q4. What Were the Benefits of the Collaboration Over Time?

To explore the benefits of collaboration, participants were asked to describe the outcomes accruable to the collaboration. Advancing their scientific understanding of the biology and ecology of the pest and its mitigation were the primary benefits of collaboration. This was described as gaining a novel understanding of location specific control strategies for SWD, capacity building in leadership, access to statewide datasets, employment and research opportunities, and expansion of the body of literature through multiple research publications.

Specifically, James reported that, “I now know that SWD needs different strategies specific to each crop and region and we have been able to develop reduced risk insecticides with non-target effects as well as insecticides for multiple modes of action.” Charles stated that he “gained significant knowledge from the discoveries made by the team and that has placed him in a better position to act in an Extension capacity.” While Grace explained that the collaboration provided junior researchers platforms to serve in leadership roles within a national research team, Eva stated that the collaboration provided students the research opportunity to build their technical bio-informatics skills and practically develop genomics sequencing libraries.

Furthermore, Daniel reported that the long-term collaboration resulted in multiple joint publications in different research areas and has also given laboratory staff and graduate students opportunities to lead research, gain experience and promote their careers in academia and industry. According to Anthony, the sustainable collaboration “allowed us to complete, finish, and continue some of the work that we started in the last project and hadn’t really completely finished and achieved our objectives.” Emmanuel stated that the collaborative efforts have enabled his graduate students to secure employment opportunities both locally and internationally.

Other attributes highlighted by the participants include increased knowledge through the practical use of a technology, which was presumed to fail, development of non-chemical-based control solutions needed by clients to manage their crop losses, development of interpersonal relationships, access to statewide integrated pest management data, new research collaborations among participants on other projects, identification and hiring of good researchers and technicians into permanent positions in their laboratories, established partnership with agrochemical firms, expansion of social network on a global scale, and attracting funding opportunities from private organizations.

Q5. What Challenges did the Participants Face in Establishing a Resilient Team?

We identified challenges that were linked to institutional and coordination complexities that are typical of diverse and multi-stakeholder collaborations. However, we found that the COVID-19 pandemic was the major constraint that imposed both laboratory and field restrictions on the collaboration as it halted travel, hiring of staff, acquisition of equipment, and other research materials. This was not surprising as the pandemic impacted all sectors globally.

While not a barrier to success, James and Anthony reported that “having big teams across many states, the number of co-PIs, multiple regions, and a number of institutions involved in the collaboration made coordination and management a bit challenging.”According to Grace, the structure of leadership was a challenge as some leaders were more effective than others. “People who naturally work well together, work together. Those who don’t naturally work well together do their own thing and they generate a lot of their data, and they are productive, but they are not productive in a coordinated approach.” Furthermore, a shift in the roles of participants as they relocated due tocareer advancement was also identified as a challenge as it caused a temporary shortage of expertise and quick implementation of collaborative decisions was impeded. Grace also explained that assumption of roles that required special social science expertise by entomologists was “a bit out of the wheelhouse” for some of the participants which increased their responsibilities.

While Jason and Daniel reported that the bureaucracy involved in securing approvals from regulatory agencies as impediments to the collaboration processes, Caleb and Emmanuel explained that due to the complicated nature of the research, available space for field work, environmental conditions, different types of crops and their production systems, some participants adapted different treatments, which limited standardization of result and availability of economic data across states.

Q6. How Did Participants Experience Communication Within the Team?

All 12 participants described the communication patterns existing among the collaborative team as “good” and “effective” by adopting different communication channels including monthly virtual meetings over Zoom®, emails, phone calls, as well as in-person visits to disseminate information and coordinate activities.

Specifically, Olivia stated that frequent communication regarding research updates reinforced the team’s ability to work closely together. This perspective was corroborated by 11 participants who stated that the regular monthly meetings structured by the team leadership to talk about all the pieces of the project contributed to the effectiveness of communications among members. While Eva explained that, “though the team is spread across the U.S., I don’t think there are necessarily any barriers or problems in terms of communication.” Jason reported that, “unlike other past research collaborations where I was a member, which felt almost secretive, and not knowing what other researchers in the team were doing, the communication here is fantastic, well-coordinated, very open and it feels nice to be a team member.” This view was supported by Caleb who stated, “the communication in this project has been really good, and it is not always like that with a lot of other projects. I am not afraid of saying what I am doing, what I am finding, and I never got the impression that someone is going to take my idea and run with it.”

Although Emmanuel explained that due to the difference in team members’ professional background, “it was initially challenging for me to communicate what my profession could bring as an economist to the project as most of the researchers thought that economists were accountants.” Nevertheless, his communication with the team members improved when they became more receptive to the analytical tools he developed to provide more economic information about their entomology work. In contrast, Grace described the communication as “kind of fragmented as some folks really pay close attention, communicate, and have a pretty strong grasp of everything that’s being done, and then there are some team members again, who are focused on their specific area and may not be super engaged with others.”

Conclusions, Discussion, and Recommendation

In conclusion, participants reported a high degree of esprit décor and low competition that resulted in a sustained long-term successful and highly productive collaboration over 15 years. Our findings have elucidated several key factors that enhanced the long-term collaboration and can be applied to other teams seeking to extend partnerships for enhanced problem solving and productivity. Our participants engaged in (a) leveraging fundamental knowledge (of SWD) from founding researchers to junior faculty, thereby expanding social capital to create a demand for professional expertise within the group; (b) sharing personal interest in knowing current research needs and trends; (c) and extending research findings across crops and regions.

The team created an atmosphere of support for each other including career development and networking for junior researchers. Members were open to sharing research ideas without fear of intellectual theft and were transparent with research activities. Other factors that contributed to success included good communication among members, integrity, collegial personalities, willingness to learn, high intelligence, commitment to hard work, and good leadership. Our findings demonstrate that successful teams are productive, and this group has successfully mitigated the destructive activities of SWD in the U.S. Consistent with the literature, we found similar benefits of collaboration including (a) creating new location and crop specific control strategies for SWD; (b) development of new non-target chemical control technology; (c) leadership capacity building and professional development for students and junior researchers; (d) sharing of information on research and Extension positions; (e) access to statewide datasets; (f) knowledge sharing, and (g) expansion of the body of literature through multiple research publications (Abramo et al., 2013; Baker et al., 2020; Gladman, 2015; Koskenranta et al., 2020; Paphawasit & Wudhikarn, 2022 ).

Nevertheless, a few challenges constrained realizing the full potential of the team including the COVID-19 pandemic, limited funding, bureaucracy in securing governmental approvals and certifications for the parasitoid project, complexity of member coordination, and relocation of members over the life of the project.

This study provides empirical evidence that interdisciplinary and multi-institutional teams serve as a vehicle for research advancement in the agricultural sector. The team used a variety of approaches to create solutions to address a complex agricultural problem that could not have been solved in isolation. Aligning with Bryson and Crosby (2015), Felin and Zenger (2014), Fernandes and O’Sullivan (2021), and Garcia et al. (2020), multi-stakeholder collaborations are often stimulated by a common problem and the decision to collaborate is influenced by competitive relevance, characterized by a diversity of knowledge among team members.

The findings from this study are relevant to principles of agricultural education, communication, and leadership in several meaningful ways. The practice of leveraging fundamental knowledge from founding researchers to junior members exemplifies effective knowledge transfer, a core principle in agricultural education (Roberts et al., 2023; Wright et.al, 2021). Agricultural education and Extension programs can incorporate these practices to foster a supportive learning environment, where emerging professionals are encouraged to develop their careers through mentorship and networking opportunities (Hur et al., 2023). The team’s approach to sharing personal interests in current research needs and trends, as well as extending research findings across crops and regions, highlights the importance of collaborative learning, which is critical for agricultural Extension (Croom et al., 2022; Franz et al., 2010, Narine et al., 2019). The team’s commitment to open communication and transparency in research activities is a cornerstone of effective agricultural communication. By fostering an environment where ideas are freely shared without fear of intellectual theft, agricultural educators can encourage a culture of trust and innovation among students and researchers (Ashfield et al., 2020).

It is recommended that agricultural professionals engage in collaborative research to showcase their expertise, attract visibility to their research, build their social capital and contribute significantly to the body of literature while solving complex problems. With the increasing call for collaboration from funding agencies, practitioners should focus on the use of improved communication tools and data-sharing software such as MS Teams, Slack, or Share point for collaboration purposes. Giving members the liberty to choose from research components of interest, prioritizing integrity and transparency regarding research activities, and demonstration of support for one another are critical factors for successful, productive, and sustainable long-term collaborative teams. Future research could explore how growers’ knowledge and experience of SWD have changed over time and the effect of these innovations on SWD on their farms. The study was limited by the scope, participant non-respondents, and the small sample size, which may impede transferability of the findings to other cases.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture (project number 2020-51181-32140), and facilitated by the University of Georgia, the University of Florida, and 12 other universities. Ajayi, D. and Kelsey, K. co-conceptualized the study, co-developed the methodology, co- collected, and analyzed the data, and co-wrote the manuscript.

References

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, C. A., & Murgia, G. (2013). The collaboration behaviors of scientists in Italy: A field level analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 7(2), 442-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.01.009

Akpan, V. I., Igwe, U. A., Mpamah, I. B. I., & Okoro, C. O. (2020). Social constructivism: Implications on teaching and learning. British Journal of Education, 8(8), 49-56. https://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/Social-Constructivism.pdf

Ankrah, S., & Omar, A. T. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387-408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2015.02.003

Arnal, Á. J. (2018) Implementation of PEF treatment at real-scale tomatoes processing considering LCA methodology as an innovation strategy in the agri-food sector. Sustainability,10(4),1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040979.

Arsenyan, J., Büyüközkan, G., & Feyzioğlu, O. (2015). Modeling collaboration formation with a game theory approach. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(4), 2073-2085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.10.010

Ashfield, A., Mullan, C., & Jack, C. (2020). Encouraging farmer participation in agricultural education and training: A Northern Ireland perspective. International Journal of Agricultural Management, 9, 96-106. https://doi.org/10.5836/ijam/2020-09-96

Baker, B. P., Green, T. A., & Loker, A. J. (2020). Biological control and integrated pest management in organic and conventional systems. Biological Control, 140, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.104095

Bekkers, R., & Bodas Freitas, I. M. (2008). Analyzing knowledge transfer channels between universities and industry: To what degree do sectors also matter? Research Policy, 37(10), 1837-1853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.07.007

Bekkers, R. N. A., & Bodas Freitas, I. M. (2011). The performance of university-industry collaborations: empirical evidence from the Netherlands. A paper presented at the DRUID 2011 on Innovation, Strategy, and Structure, Organizations, Institutions, Systems and Regions. 1-36. https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/57881156/448150161855381.pdf

Blanco, C. D. P. (2020) Water availability risk in agriculture: An application to guadalquivir and segura river basins. Estudios de Economia Aplicada, 29(1), 333-357. https://doi.org/10.25115/EEA.V29I1.3942.

Bodin, O. (2017). Collaborative environmental governance: Achieving collective action in social-ecological systems. Science, 357(6352).1-8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan1114

Brown, P., Von Daniels, C., Bocken, N. M. P., & Balkenende, A. R. (2021). A process model for collaboration in circular oriented innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125499

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Harvard University Press.

Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2015). Designing and implementing cross sector collaborations: Needed and challenging. Public Administration Review. 75(5), 647-663. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12432.

Cantner, U., Hinzmann, S., & Wolf, T. (2017). The coevolution of innovative ties, proximity, and competencies: Toward a dynamic approach to innovation cooperation. Knowledge and Networks, 11, 337–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45023-0_16

Coutts, J., Long, P., & Murray-Prior, R. (2017, June 19). Strengthening practice change, education and Extension in reef catchments, Extension approaches and methods. COUTTS J & R. https://reefextension.couttsjr.com.au/

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design (2nd ed.). Sage.

Creswell J. W. (2013). Research design. Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. (4th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. (5th ed.). Sage.

Cronin, B., Shaw, D., & La Barre, K. (2003) A cast of thousands: Co-authorship and subauthorship collaboration in the twentieth century as manifested in the scholarly literature of psychology and philosophy. Journal of American Sociology Information Science and Technology, 54(9), 855-871. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10278

Croom, D. B., Yopp, A. M., Edgar, D., Roberts, R., Jagger, C., Clemons, C., & Wagner, J. (2022). Technical professional development needs of Agricultural Education teachers in the southeastern United States by career pathway. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 73(73),132. https://jsaer.org/page/2/?cat=-1

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2008). Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Sage.

Díaz, M. (2021). Environmental objectives of Spanish agriculture: Scientific guidelines for their effective implementation under the common agricultural policy 2023-2030. Ardeola,68(2), 445-460. https://doi.org/10.13157/arla.68.2.2021.fo1.

Doolittle, P. E. & Camp, W. G. (1999). Constructivism: The career and technical education perspective. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 16(1), 23-46. https://doi.org/10.21061/jcte.v16i1.706

Doussou-Kpanou, B. D., Kelsey, K., & Bower, K. (2020). An evaluation of social networks within federally funded research projects. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 1(3), 42-54. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v1i3.65

Duţă, N., & Martínez-Rivera, O. (2015). Between theory and practice: the importance of ICT in higher education as a tool for collaborative learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 180, 1466-1473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.294

Eaton, W. M., Brasier, K. J., Whitley, H., Bausch, J. C., Hinrichs, C. C., Quimby, B., Burbach, M.E., Wutich, A., Delozier, J., Whitmer, W., Kennedy, S., Weigle, J., & Williams, C. (2022). Farmer perspectives on collaboration: Evidence from agricultural landscapes in Arizona, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania. Journal of Rural Studies, 94, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.05.008

Felin, T., & Zenger, T. R. (2014).Closed or open innovation? Problem solving and the governance choice. Research Policy, 4(5), 914-925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.09.006

Fernandes, G. & O’Sullivan, D. (2021). Benefits management in university-industry collaboration programs. International Journal of Project Management, 39(1), 71-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.10.002

Foray, D., & Steinmueller, E. (2003). On the economics of R&D and technological collaborations: Insights and results from the project Colline. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 12(1), 77-91. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438590303118

Franz, N., Piercy, F., Donaldson, J., Richard, R., & Westbrook, J. (2010). How farmers learn: Implications for agricultural educators. Journal of Rural Social Sciences,25(1),37-59. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jrss/vol25/iss1/

Garcia, R., Araújo, V., Mascarini, S., Santos, E. G., & Costa, A. R. (2020). How long-term university-industry collaboration shapes the academic productivity of research teams. Innovation, 22(1), 56-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2019.1632711

Gasper, P. (1999). Social constructivism. In R. Audi (Ed.), The Cambridge dictionary of philosophy (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Geissdoerfer, M., Vladimirova, D., & Evans, S. (2018). Sustainable business model innovation: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production. 198, 401-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.240

Gladman, A. (2015). Team teaching is not just for teachers! Student perspectives on the collaborative classroom. TESOL Journal, 6(1), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.144

Gray, B. (1989). Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems.Jossey-Bass.

Hill, R., Grant, C., George, M., Robinson, C. J., Jackson, S., & Abel, N. (2012). A typology of indigenous engagement in Australian environmental management: implications for knowledge integration and social-ecological system sustainability. Ecology and Society, 17(1), 23-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26269005

Hur, G., Roberts, T. G., Diaz, J., Diehl, D., & Bunch, J. C. (2023). Exploring teaching-focused personal networks of agriculture university faculty members: A mixed-methods egocentric network approach. Journal of Agricultural Education,64(1), 28-45. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.v64i1.28

Ikendi, S., Retallick, M. S., Nonnecke, G. R., & Kugonza, D. R. (2023). Influence of school garden learning approach on academic development of global service-learners. Journal of Agricultural Education, 64(4), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.v64i4.167

Jeong, S., Choi, J. Y., & Kim, J. (2011). The determinants of research collaboration modes: Exploring the effects of research and researcher characteristics on co-authorship. Scientometrics, 89(3), 967-983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0474-y

Kant, I., Meiklejohn, J. M. D., Abbott, T. K., & Meredith, J. C. (1934). Critique of pure reason. JM Dent.

Kelly, J., & Cherkowski, S. (2015). Collaboration, collegiality, and collective reflection: A case study of professional development for teachers. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 169, 1-27. https://cdm.ucalgary.ca/index.php/cjeap/article/view/42876

Koskenranta, M., Kuivila, H., Männistö, M., Kääriäinen, M., & Mikkonen, K. (2022). Collegiality among social-and health care educators in higher education or vocational institutions: A mixed-method systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 114,1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105389

Lamm, K. W., & Carter, H. S. (2019). Leadership development program evaluation: A social network analysis approach. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 69(1), 4-19. https://jsaer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/2019_004-final-print.pdf

Li, K. M. (2015). Learning styles and perceptions of student teachers of computer-supported collaborative learning strategy using wikis. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(1), 32-50. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.521

Macknick, J., Hartmann, H., Barron-Gafford, G., Beatty, B., Burton, R., Seok-Choi, C., Davis, M., Davis, R., Figueroa, J., Garrett, A., Hain, L., Herbert, S., Janski, J., Kinzer, A., Knapp, A., Lehan, M., Losey, J., Marley, J., MacDonald, J., & Walston, L. (2022). The 5 Cs of Agrivoltaic success factors in the United States: Lessons from the InSPIRE research study, United States. A technical report, 1-80. https://doi.org/10.2172/1882930

Margerum, R. D., & Robinson, C. J. (Eds.). (2016). The challenges of collaboration in environmental governance: barriers and responses. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Marlows, M. P., & Nass-Fukai, J. (2000). Collegiality, collaboration, and kuleana: Three crucial components for sustaining effective school-university partnerships. Education, 121(1), 188-194. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A66960822/AONE?u=tall22798&sid=googleScholar&xid=f666f6f2

Mcleod-Morin, A., Rumble, J. N., & Telg, R. W. (2021). Challenges and motivations of science communication: An administrative perspective at land-grant universities. Journal of Applied Communications, 105(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.2387

McLeod-Morin, A., Telg, R., & Rumble, J. (2020). Describing interdisciplinary agricultural research center directors’ perceptions of science communication through goals and beliefs. Journal of Applied Communications, 104(1),1-18. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.2300

Merriam, S. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. Jossey-Bass.

Mishra, D., & Mishra, A. (2009). Effective communication, collaboration, and coordination in extreme programming: Human‐centric perspective in a small organization. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing and Service Industries, 19(5), 438-456. https://doi.org/10.1002/hfm.20164

Narine, L. K., Harder, A., & Zelaya, P. (2019). A qualitative analysis of the challenges and threats facing Cooperative Extension at the county level. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 69(1), 20-32. http://www.jsaer.org/pdf/Vol69/2019_008%20final%20print.pdf

Paphawasit, B., & Wudhikarn, R. (2022). Investigating patterns of research collaboration and citations in science and technology: A case of Chiang Mai University. Administrative Sciences, 12(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020071

Pham, H. T., & Tanner, K. (2015). Collaboration between academics and library staff: A structurationist perspective. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 46(1), 2-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2014.989661

Purdy, J. M. (2012). A framework for assessing power in collaborative governance processes. Public Administration Review, 72(3), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02525.x

Reed, D. B., McCallum, D., & Claunch, D. T. (2021). Changing health practices through research to practice collaboration: The farm dinner theater experience. Health Promotion Practice, 22(1), 122-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839921996298

Rensfeldt, A. B., Hillman, T., & Selwyn, N. (2018). Teacher’s ‘liking’ their work? Exploring the realities of teacher Facebook teams. British Educational Research Journal, 44(2), 230-250. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3325

Roberts, T. G., Cardey, S., & den Brock, P. (2023). Developing a framework for using local knowledge systems to enhance capacity building in agricultural development. Advancements in Agricultural Development,4(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v4i2.305

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. (5th ed.). Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Saldaña, J., & Omasta, M. (2020). Qualitative research: Analyzing life (2nd ed.). Sage.

Seevers, B., Graham, D., Gamon, J., & Conklin, N. (1997). Education through Cooperative Extension. Delmar Publishers.

Sial, A., Burrack, H., Loeb, G., Isaacs, R., Walton, V., Zalom, F., Daane, K. Chiu, J., Rodriguez-Saona, C., Beers, E., Northfield, T., Fanning, P., Hoelmer, K., Wang, X., Hoheisel, G., Gallardo, K., Gomez, M., & Kelsey.K. (2020). Moving from crisis response to long-term integrated management of SWD: A keystone pest of fruit crops in the United States. Proposal submitted to USDA-NIFA for funding. https://portal.nifa.usda.gov/web/crisprojectpages/1023475-moving-from-crisis-response-to-long-term-integrated-management-of-swd-a-keystone-pest-of-fruit-crops-in-the-united-states.html

Schubert, A., & Glanzel, W. (2006). Cross-national preferences in co-authorship, references and citations. Scientometrics, 69(2), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-006-0160-7

Skelcher, C., Sullivan, H., & Jeffares, S. (2013). Hybrid governance in European cities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Storksdieck, M., Shirk, J. L., Cappadonna, J. L., Domroese, M., Göbel, C., Haklay, M., Miller-Rushing, A.J., Roetman,P., Sbrocchi, C., & Vohland, K. (2016). Associations for citizen science: regional knowledge, global collaboration. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice, 1(2), 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/cstp.55

Sulandjari, K., Putra, A., Sulaminingsih, S., Adi, C. P., Yusroni, N., & Andiyan, A. (2022). Agricultural extension in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic: Issues and challenges in the field. Caspian Journal of Environmental Sciences, 20(1), 137-143.https://doi.org/10.22124/cjes.2022.5402

Tartari, V., & Breschi, S. (2012). Set them free: Scientists’ evaluations of the benefits and costs of university-industry research collaboration. Industrial and Corporate Change, 21(5), 1117–1147. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts004

Thorgersen, K. A., & Mars, A. (2021). A pandemic as the mother of invention? Collegial online collaboration to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic. Music Education Research, 23(2), 225-240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2021.1906216

van der Wal, J. E. M., Thorogood, R., & Horrocks, N. P. C. (2021). Collaboration enhances career progression in academic science, especially for female researchers. Proceedings Royal Society, 288, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2021.0219

Velten, S., Jager, N.W. & Newig, J. (2021) Success of collaboration for sustainable agriculture: A case study meta-analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability,23, 14619–14641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01261-y

Ward, C., Holmes, G., & Stringer, L. (2018). Perceived barriers to and drivers of community participation in protected‐area governance. Conservation Biology, 32(2), 437-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13000

Worley, B., Fuhrman,N., & Peake, J. (2021).A quantitative approach to identifying turfgrass key players. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 2(1), 83-95. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v2i1.85

Wright, K. M., Rolling Meadows, I. L., Hauser, A., & Maxwell, L. D. (2021). Designing a technique for program expansion of secondary agricultural education. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 71(1), 43-60. https://jsaer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/71-Wright-Vincent-Hauser-Maxwell.pdf

Wuchty, S., Jones, B. F., & Uzzi, B. (2007). The increasing dominance of teams in production of knowledge. Science, 316(5827), 1036–1049. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1136099

Yin, R.K. (2003). Case study Research: Design and Methods (3rd ed.). Sage.