Callan Hand, Tift County Schools, Georgia

Ashley M. Yopp, Florida Department of Education

D. Barry Croom, University of Georgia, dbcroom@uga.edu

James C. Anderson II, University of Georgia

Aaron Golson, University of Georgia

Abstract

This study explored how agricultural education can increase the retention of non-traditional, urban agriculture students of color by supporting students’ academic and career goals while identifying the motivational factors related to student retention in agriculture. This explored teachers’ perceptions of their students’ motivation to stay in agriculture. The data were collected through interviews. The data were analyzed by qualitative methodology. Teachers expressed concern about students’ futures in agriculture and their hope to push students toward a future in agriculture. This was based on several key factors that either encouraged or thwarted their engagement in agriculture.

Introduction

Teachers support students of color in Career and Technical Education (CTE) by eliminating barriers, promoting inclusivity, and providing guidance and resources (Warren & Alston, 2007). They advocate for equal opportunities, address biases, and create inclusive classroom environments that encourage collaboration and respect. This is particularly important for students of color in agricultural education, as the job market in this field is strong. The U.S. Department of Agriculture projects a high demand for graduates in agriculture and natural resources (Goecker et al., 2015), with 22 million jobs related to agriculture and food sectors in 2018 (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, 2023). However, students of color pursue agricultural careers at lower rates than their Caucasian counterparts (Silas, 2016).

Despite progress in Black student participation in schools (Levine & Levine, 2014), retaining them in agricultural professions remains challenging (Vincent et al., 2012). Many minority youths perceive agriculture as low-paying, lacking prestige, and demanding excessive work for inadequate wages (Dumas, 2014; Larke & Barr, 1987; Talbert et al., 1999). Historical exclusionary policies and a lack of representation in the agricultural industry contribute to this perception, limiting access to role models and mentors. These experiences have led to a distrust of the field and low interest in pursuing agricultural careers.

Negative stereotypes about farming and agriculture also discourage Black students, who may see it as physically demanding, low-paying, and offering limited growth opportunities, mainly if they

come from urban backgrounds with little exposure to agriculture.

Theoretical Framework: Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT)

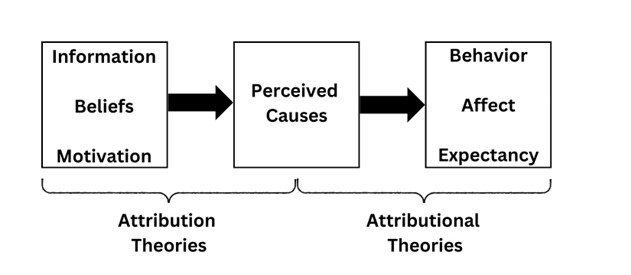

Our research was guided by social cognitive career theory (SCCT) developed by Lent and Brown (2002). SCCT provides a comprehensive lens for examining career development and motivation, emphasizing self-efficacy beliefs, outcome expectations, interests, goals, and social influences in shaping career choices. We explored teachers’ views on students’ self-efficacy in agriculture and the factors contributing to or hindering its development. We also examined students’ expectations about benefits and opportunities in agriculture careers. We also investigated students’ interests in agriculture, career-related objectives, and teachers’ influence on their career decisions, including cultural and societal factors. Furthermore, we assessed the unique barriers students of color face in pursuing agricultural careers and their impact on motivation. SCCT guided our analysis of teachers’ perceptions, identifying opportunities for intervention and support to enhance students’ motivation and success in agriculture.

Research Objectives

The research objective was to describe teachers’ perceptions of students’ motivation to enroll in agriculture courses and pursue agricultural careers upon graduation.

Agricultural Education in Urban Schools

For most of the twentieth century, agricultural education has focused its attention on teaching traditional production agriculture (Croom, 2008; Talbert et al., 2022) to students who were usually rural, white males who grew up on a farm (Dyer & Breja, 2003). However, in the last twenty years, agricultural education and career and technical education, in general, have embraced a more diverse student population (Xing et al., 2019). Non-traditional, secondary agricultural education programs are typically urban and diverse in student enrollment and curriculum (Lawrence et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2013; Yopp et al., 2018). As the student population in the United States continues to diversify, it has become increasingly crucial for agricultural educators to tap into students’ varying backgrounds and cultures to make real-life connections between what they learn in the classroom and a future in agriculture (Esters & Bowen, 2005). This support is accomplished by utilizing student interests, background, and culture in teaching. Barton and Tan (2009) investigated student diversity by studying low-income urban students and their cultural backgrounds. They found that the cultural knowledge and resources that urban youth bring to a classroom are essential elements in student engagement in the classroom. Students are willing to use their funds of knowledge openly in the classroom because the teacher invited them to do so in the classroom lessons and activities (Kenny & Bledsoe, 2005; Westbrook & Alston, 2007).

Methodology

This study employed a phenomenological approach involving interviews with two agriculture teachers at a model urban agricultural education program.

Demographic Data and Descriptions of Participants

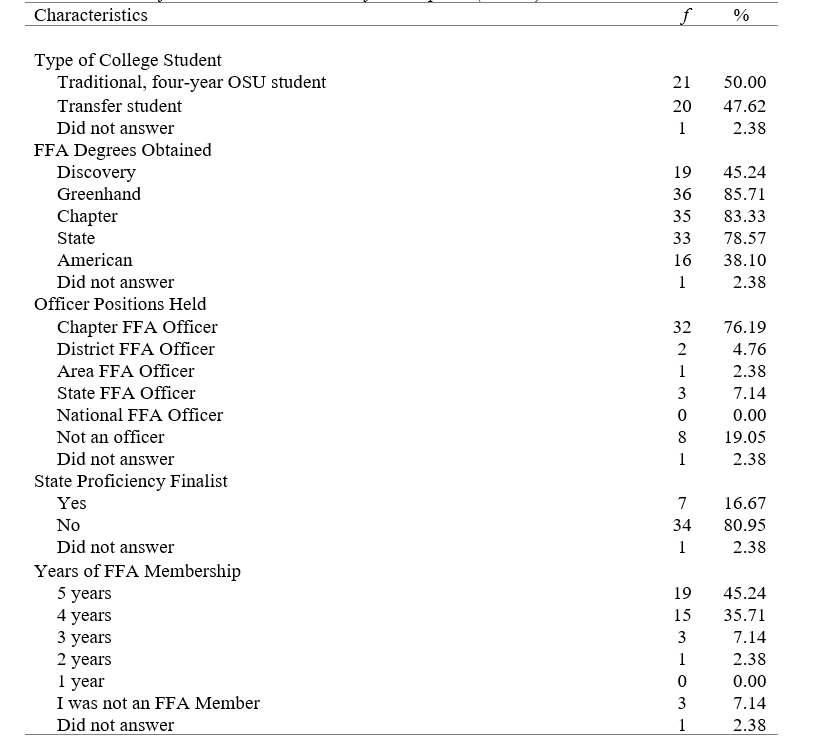

The researchers met with the school’s lead administrator to identify suitable teachers for the study. Teacher One was a white female biotechnology teacher, coded as Teacher One. Teacher Two was an African-American female horticulture teacher, coded as Teacher Two.

Data Collection

We used a semi-structured interview with teachers. Pre-determined questions guided the first discussion; however, we used probing questions to encourage the participants to elicit deeper thinking about their responses. These questions were designed to elicit thoughts and opinions about the students’ lived experiences in the classroom from a teacher’s perspective to learn more about students’ support systems within the school setting. We made observational notes throughout the study, using techniques recommended by Leatherman and Niemeyer (2005).

Data Analysis

We utilized template analysis, a method of thematically analyzing qualitative data (King, 2023). Template analysis was chosen as the method of data analysis for this study because the researchers sought to understand participants’ lived experiences, thoughts, and behaviors with common and shared meanings through semi-structured interviews and a questionnaire (Braun & Clarke, 2012). This method often begins with a priori codes to help identify themes potentially relevant to the analysis (King, 2023). Once a priori themes were defined, we read through the data, marking segments that appeared to tell us something of relevance to the research question. New themes were defined to include the relevant material and organized into an initial template. We transcribed the teacher interviews and became familiar with the entire data set against relevant segments of previous data found on the research topic. We coded each response and divided the codes into themes. After the themes were developed, we included quotes from study participants that best supported the themes. We used informal member checking, a standard method to maintain validity and establish trustworthiness in qualitative research (Candela, 2019; Lincoln & Guba, 1985). This was achieved by following up with the two teachers in the study. We sent emails to both teachers with quotes made by each one to ensure that what they said in the interview was accurate. The researchers also employed reflexivity related to the researcher’s perceptions and opinions on the research topic— the internal and external values that impact non-traditional, urban agriculture students’ intent to stay in agriculture.

Findings

Description of School Site

The Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences is a specialized public high school located on the southwest side of a major midwestern city. It was established in 1985 to provide urban students with agricultural education opportunities. It serves around 700 students in grades 9-12, offering a rigorous college preparatory curriculum emphasizing science, math, and technology. The school provides hands-on learning experiences in agriculture and environmental science, including access to a campus farm with a greenhouse, livestock barns, and crop fields. Students can engage in extracurricular activities such as FFA, 4-H, and environmental clubs, and [The School] has received recognition for its innovative educational program.

Unique to the Midwest, this school offers urban students interested in science and math the chance to expand their agricultural knowledge through various pathways, including Agricultural Finance, Agricultural Mechanics, Animal Science, Food Science and Technology, Horticulture, and Biotechnology in Agriculture. The student population comprises a diverse mix, with approximately 48% African American, 31% White, 19% Hispanic, and 0.1% Asian, totaling 804 students during the data collection year. The school’s mission is to prepare and engage students in urban agriculture careers (Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences, 2021).

Teacher Perceptions of Student Interest in Agricultural Education

Participants in the study identified several themes affecting student engagement in agriculture, including (1) inclusion and representation, (2) overcoming challenges, (3) urban-rural divide, (4) fostering connections, (5) recognizing student achievements and skills, (6) providing a supportive learning environment, and (7) creating relevant, relatable curriculum.

During interviews, teachers mentioned two agricultural youth organizations: The National FFA Organization (FFA) and Minorities in Agriculture, Natural Resources, and Related Sciences (MANRRS). FFA, founded in 1928, is the largest U.S. student-led organization, boasting over 700,000 members from all states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (National FFA Organization, 2022). MANRRS, established in 1986, promotes diversity and inclusion in agriculture and related fields, advocating for underrepresented minority groups (MANRRS, 2023).

A Seat at the Table

When discussing whether or not urban students had a disadvantage in agriculture, Teacher One said that her students indeed have a disadvantage. Industry professionals and fellow educators have told her that urban agriculture students have nothing to offer to the field. As Teacher One expressed:

It’s very disheartening when you hear some of the things that have been said or spoken to [students] or questions that were asked, like within the same organization, in the same state, everyone studying agriculture. And a lot of it is just the lack of knowledge or ignorance of youth. But I feel that the students that I teach have a double whammy. So, they have cultural differences when they are put into different groups, and then they have the urban stereotype.

To Teacher One, the most significant barrier between urban and rural students was the lack of camaraderie between the two groups. Teacher Two discussed how her students constantly have to fight the city stereotype of being from a large Midwestern city when they travel to other places for ag-related events. On top of this, students have to fight the cultural differences between students at these events. Because of these two things, she said her students have the added barrier of being both an urban agriculture student and an agriculture student of color. One teacher discussed how agricultural youth organizations seek to improve diversity at events and programs with cultural diversity and inclusion training. However, there is a long way to go. When discussing FFA, Teacher Two discussed how she believes FFA has been ineffective at making their organization relatable to students of color. She explained that, in her opinion, FFA needs to take more action and shift how it reaches urban students so that students can see that they are wanted, seen, and heard and ultimately become more invested in agriculture. As Teacher Two described it,

MANRRS is a little bit smaller on the scale aspect, but they provide the same things, but it feels more like home with them versus, like I said, being a stranger in a familiar place… you don’t want to be in a room where you feel uncomfortable, you feel unwanted, or you can’t relate. And I think FFA has done a poor job at making it relatable to people of color…They need to stop talking and [take] more action, shifting how they’re reaching the urban dynamic, and maybe we’ll have more people invested in it if they show that they’re wanted.

Teachers of students of color feel that their students are “outsiders looking in” because they feel they cannot contribute anything to the field of agriculture. Urban agriculture students are not treated respectfully in agricultural organizations, even though students of color want recognition and a seat at the table.

Genuine Inclusiveness

Regarding inclusiveness and the importance of ensuring students feel safe in agriculture, Teacher Two felt that teachers are not making students feel comfortable in agriculture. Because if students of color do not feel safe, they will not see how agriculture relates to their lives. Teacher One stated:

And so it’s generally when we go to different state-wide events when we open it up to where they’re interacting with kids outside of the city limits. It’s gotten to a point where things are looking at getting changed to have like cultural diversity training and inclusion training and looking at how we can change the organization both at a national level and at a state level, because we talk about diversity and how important that is, and this is for all kids involved in agriculture. But is it accepting of all? How comfortable do the students feel?

One teacher emphasized the importance of educating the next generation about agriculture’s role in feeding the world and nurturing future agriculture leaders. Both teachers strive to make their curriculum relatable and highlight the interconnectedness of everything with agriculture. However, students often fail to see these connections and lack exposure to genuine inclusion efforts, leading to discomfort in agricultural environments and reduced interest in the field. Teacher Two succinctly summarized this issue:

We’re in the era of truth. And the point is, no, we’re not doing our due diligence when it comes to making our kids feel comfortable and safe in ag. And if they don’t feel safe, they don’t see how it’s relatable. They don’t see the benefit other than ‘Oh I get to eat and I have some clothes on my back, maybe a house.’ The students ask, ‘Why would I get invested in these programs? Why would I stick with these organizations? Why would I support these organizations? They’ve done nothing for me.

Ag is a Hard Sell

When discussing prior negative experiences with students at FFA events, Teacher Two discussed how she had noticed more and more of her students going to MANRRS over FFA. She explained that agriculture is a “hard sell” culturally for her African-American students because her students correlate agriculture to slavery. As Teacher Two reported:

But it’s a hard sell, and especially culturally, black people believe that you know, you’re taking me back to the cotton fields kind of thing when they’re farming… like slave labor. I hear that so much. It’s very distressing to hear.

Because of this, she expressed that her students are not interested in pursuing agriculture. Teacher Two added that from her perspective, students are not interested in agriculture and would rather be doctors, lawyers, or pursue prestigious professions. She explained that no one is telling students to pursue careers in soil science and how this bothers her because students think it does not pay well.

No one’s telling kids to be in soil science…Why?? There are so many jobs in soil…And they pay a lot of money and the kids don’t even know…They say no, that’s not fun, I don’t want to do that. I want to be a doctor. So…when we get them there, we can sway a good group of kids to stay in it (Teacher One ).

She further explained that if students are recruited to this field, they can sway a good group of kids to remain in the field long-term. However, before this can happen, students need to feel comfortable and safe and see positive change within their agriculture organizations. When students feel safe, they will be more likely to become interested in pursuing future agriculture opportunities.

Formative Experiences

Teacher One stressed the need to cultivate students’ early appreciation for agriculture outside the classroom. Her own experiences showed how early exposure enriches understanding and sustains interest. She cited an example of a student aspiring to a production agriculture career, underscoring the importance of early exposure in nurturing students’ agricultural interests.

We’re in the era of truth. And the point is, no, we’re not doing our due diligence when it comes to making our kids feel comfortable and safe in ag. And if they don’t feel safe, they don’t see how it’s relatable. They don’t see the benefit other than ‘oh I get to eat and I have some clothes on my back, maybe a house.’ The students ask, ‘why would I get invested in these programs? Why would I stick with these organizations? Why would I support these organizations? They’ve done nothing for me. (Teacher One)

Outside the City Limits

Both Teacher One and Teacher Two talked about how important it is to expose their students to the outside world and give them opportunities to experience agriculture outside of the city where they live. Teacher One discussed how many of her students fear being in an environment without street lights or the comforts they grew up in the city. Therefore, she has found that many students do not have many interactions with the environment outside of the city limits, so they are struggling to make the connections between what they learn in the classroom and the greater aspect of agriculture.

To be in an environment without streetlights or without the standard city parts that they grew up with…the comfort…the students don’t have as much interaction with that. So…with the school, that’s one of the things that we try to give them…those types of experiences…so that they can see what else is out there (Teacher One).

Overall, the teachers found that urban students lack exposure to agriculture outside the classroom. They are not connecting with agriculture on a larger scale because it is not relatable to them in this stage of life. These students are not concerned with the more significant problems they will eventually face once they are out of the classroom. Therefore, students need more meaningful and unique experiences that expose them to the outside world beyond their urban dynamic. In doing so, students will more likely see the value of agriculture and its impact on their lives.

Making the Connection

In discussing the urban students’ barriers in agriculture, Teacher One explained that students could not see the production process and make the farm-to-table connection.

…there’s a disconnect between the food and the production side and understanding how those products get to the market. I also think that [students] are at a slight disadvantage as well, because if they don’t follow through with what is actually happening, once the products leave the farm or whatever step they are in, they’re there in retail and they’re sold then [so students don’t see the connection] (Teacher One).

On this same topic, Teacher Two explained how she grew up in the urban dynamic. Because of this, she works hard to make her agriculture curriculum relatable to her students’ lives whenever possible. Furthermore, she discussed how she shows her students that everything they touch deals with agriculture, and that helps students connect the food on their plates and their own lives. When students can connect agriculture with their own lives, they are more likely to be interested in agriculture and what it offers.

So, since I come from the urban dynamic, I think I try to make it as relatable as possible, and especially when we’re developing this urban ag curriculum for our students. I try to show them that everything that you do and everything that you touch and everything that is around you is dealing with agriculture. And they don’t get it because it’s just like, ‘well, how do I relate this back’? (Teacher Two).

Conclusions and Discussion

The findings of this study reveal the complexities and challenges urban students face in engaging with agricultural education, particularly within the unique context of [The School]. This specialized public high school aims to bridge the urban-rural divide by offering a curriculum focused on science, math, and technology through the lens of agriculture. Despite the school’s innovative approach and the diverse student population, several significant barriers hinder students’ full engagement and interest in agriculture.

Inclusiveness and Representation

One of the predominant themes identified was the need for greater inclusiveness and representation in agricultural education and related organizations. Teachers reported that students often feel like “outsiders looking in,” particularly in organizations like FFA, which have not effectively addressed these students’ cultural and urban backgrounds. This lack of representation contributes to alienation and disinterest in pursuing agricultural careers. Organizations must prioritize genuine inclusiveness to address this, ensuring all students feel seen, heard, and valued.

Overcoming Cultural and Urban-Rural Challenges

The study highlights urban students’ cultural and urban-rural challenges in agricultural settings. Teachers emphasized that their students often combat stereotypes and biases, both from within the industry and from their peers in rural areas. This dual disadvantage can discourage students from engaging deeply with agricultural education. Programs like MANRRS have shown promise in creating a more welcoming environment, but broader efforts are needed to change perceptions and increase cultural competence within the field.

Fostering Connections and Relevance

Another critical finding is that teachers believe in making agricultural education relatable to urban students. Teachers stressed connecting classroom learning with students’ experiences and the broader agricultural context. This includes helping students see the farm-to-table process and understand the relevance of agriculture in their daily lives. Educators can foster a more profound interest and appreciation for the field by contextualizing agriculture within an urban framework.

Supportive Learning Environments

Creating supportive and safe learning environments is crucial for encouraging student engagement. Teachers reported that students need to feel comfortable and secure to see agriculture as a viable and appealing career path. This involves physical safety and emotional and cultural safety, where students’ backgrounds and experiences are respected and valued. Efforts to improve diversity training and inclusion practices at both state and national levels are steps in the right direction but require sustained commitment and action.

The Role of Early Exposure and Extracurricular Activities

Early exposure to agriculture and involvement in extracurricular activities like FFA and MANRRS play significant roles in shaping students’ perceptions and interests. Teachers noted that students who engage with agriculture outside the classroom develop a stronger connection to the field through hands-on experiences and exposure to rural environments. This early engagement is vital for nurturing long-term interest and commitment to agricultural careers.

Addressing Negative Perceptions and Enhancing Recruitment

African American students who associate farming with slavery and labor-intensive work are less likely to see agriculture in a positive light. Educators must work to dispel these myths and highlight the diverse and lucrative career opportunities within agriculture, such as soil science, biotechnology, and agricultural finance. Effective communication about the benefits and possibilities of agriculture is essential to attract and retain students.

Recommendations

The study underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to improving urban students’ engagement with agricultural education. Key strategies include enhancing inclusiveness and representation, overcoming cultural and urban-rural challenges, making curriculum relevant, creating supportive environments, providing early exposure, and addressing negative perceptions. By implementing these strategies, [The School] and similar institutions can better prepare and inspire urban students to pursue fulfilling careers in agriculture, contributing to a more diverse and dynamic agricultural industry.

Future research should explore the long-term impacts of these interventions and identify additional methods to support urban students in agricultural education. Moreover, continued collaboration between educational institutions, agricultural organizations, and communities is essential to create a more inclusive and engaging agricultural education system for all students.

References

Barton, A. C., & Tan, E. (2009). Funds of knowledge and discourses and hybrid space. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(1), 50–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20269

Barton, A. C., & Tan, E. (2009). Funds of knowledge and discourses and hybrid space. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 46(1), 50–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20269

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Candela, A. G. (2019). Exploring the function of member checking. The Qualitative Report, 24(3), 619–628.

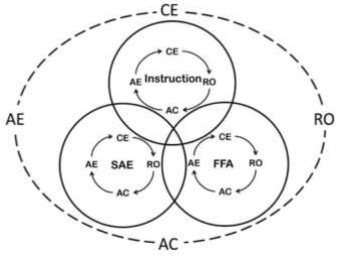

Croom, B. (2008). Development of the integrated three-component model of agricultural education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(1), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2008.01110

Dumas, J. A. G. (2014). Factors that influence Black and Latino high school students to pursue careers in agriculture. The Pennsylvania State University.

Esters, L. T., & Bowen, B. E. (2005). Factors influencing career choices of urban agricultural education students. Journal of Agricultural Education, 46(2), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2005.02024

Goecker, A. D., Smith, E., Fernandez, J. M., Ali, R., & Theller, R. (2015). Employment opportunities for college graduates in food, agriculture, renewable natural resources, and the environment, United States, 2015-2020. Purdue University.

Kenny, M. E., & Bledsoe, M. (2005). Contributions of the relational context to career adaptability among urban adolescents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.10.002

King, N. (2023). What is template analysis? University of Huddersfield.

Larke, A., & Barr, T. P. (1987). Promoting minority involvement in agriculture. The Agricultural Education Magazine, 60.

Lawrence, S., Rayfield, J., Moore, L. L., & Outley, C. (2013). An analysis of FFA chapter demographics as compared to schools and communities. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(1), 207–219. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2013.01207

Leatherman, J. M., & Niemeyer, J. A. (2005). Teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion: Factors influencing classroom practice. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 26(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901020590918979

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2002). Social cognitive career theory. Career choice and development. In D. Brown (Ed.), Career Choice and Development (pp. 255–311). John Wiley & Sons.

Levine, M., & Levine, A. G. (2014). Coming from behind: A historical perspective on Black education and attainment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099861

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE.

MANRRS. (2023). About us. MANNRS. https://www.manrrs.org

National FFA Organization. (2022). 2022-23 official FFA manual. National FFA Organization.

Robinson, J. S., Kelsey, K. D., & Terry, R. (2013). What images show that words do not: Analysis of pre-service teachers’ depictions of effective agricultural education teachers in the 21st century. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(3), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2013.0126

Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences. (2021). About the Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences. About the Chicago High School for Agricultural Sciences.

Silas, M. A. (2016). Improving the pipeline for students of color at 1862 colleges of agriculture: A qualitative study that examines administrators’ perceptions of diversity, barriers, and strategies for success [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Talbert, B. A., Croom, B., LaRose, S., Vaughn, R., & Lee, J. S. (2022). Foundations of agricultural education (4th edition). Purdue University Press.

Talbert, B. A., Larke, Jr., Alvin, & Jones, W. A. (1999). Using a student organization to increase participation and success of minorities in agricultural disciplines. Peabody Journal of Education, 74(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje7402_8

United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (2023). Ag and food sectors and the economy. USDA Economic Research Service.

Vincent, S., Henry, A., & Anderson, J. (2012). College major choice for students of color: Toward a model of recruitment for the agricultural education profession. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(4), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.04187

Warren, C. K., & Alston, A. J. (2007). An analysis of diversity inclusion in North Carolina secondary agricultural education programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(2), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2007.02066

Westbrook, J. R., & Alston, A. J. (2007). Recruitment and retention strategies utilized by 1890 land grant institutions in relation to African American students. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(3), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2007.03123

Xing, X., Garza, T., & Huerta, M. (2019). Factors influencing high school students’ career and technical education enrollment patterns. Career and Technical Education Research, 44(3), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.5328/cter44.3.53

Yopp, A., McKim, B., & Homeyer, M. (2018). Flipped programs: Traditional agricultural education in non-traditional programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 59(2), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2018.02016