Jillian C. Ford, Auburn University, jcf0088@auburn.edu

Misty D. Lambert, North Carolina State University, mdlamber@ncsu.edu

Wendy J. Warner, North Carolina State University, wjwarner@ncsu.edu

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify the needs and concerns of new agricultural teachers participating in the DELTA induction program in North Carolina. This descriptive survey study was administered through Qualtrics in March 2023 and received responses from 22 DELTA participants who were all in their first two years teaching school-based agricultural education. The questionnaire included three components: (1) identifying needs in four construct areas related to FFA/SAE, curriculum and instruction, program management and planning, as well as professional development, (2) an open-ended question about teacher concerns, and (3) demographic questions. Participants indicated a level of need for all four constructs. Items related to program management and planning were recognized as the highest need, and those related to professional development were the lowest. Teacher concerns were concentrated in the task category. Recommendations for practice and future research are provided.

Introduction/Theoretical Framework

The ongoing demand for agriculture teachers is a prominent concern across the profession. This is not a recent phenomenon, as Hillison (1987) noted the rapid growth of agricultural education in secondary schools during the early 20th Century, which initiated the teacher shortage. Currently, the need for qualified agriculture teachers remains (Smith et al., 2022), raising questions about the best approaches to recruitment and retention. While recruitment efforts have been made on the national level to promote careers in school-based agricultural education (National Association of Agricultural Educators, 2023), and research has been done on what attracts students to the teaching profession (Andreatta, 2023; Korte et al., 2020; Lawver & Torres, 2012), this study focused on what teacher educators can do to help best support and retain beginning agriculture teachers through the delivery of an induction program in North Carolina.

To develop and facilitate meaningful professional development programming, agricultural education faculty members have employed several approaches, both quantitative and qualitative, to assess the needs of early career agriculture teachers. Quantitative approaches have commonly utilized needs assessments to identify the needs of beginning teachers (Birkenholz & Harbstreit, 1987; Garton & Chung, 1996; Washburn et al., 2001). Qualitative inquiries have included an ethnographic approach to explore problems and issues encountered by beginning agriculture teachers (Mundt, 1991) and a case study approach to document the experiences of three beginning agriculture teachers throughout a school year (Talbert et al., 1994).

As an increasing number of alternatively licensed teachers began entering the profession, Roberts and Dyer (2004) recognized the importance of identifying teachers’ perceived needs based on their route to certification, either through a traditional teacher preparation program or through alternative licensure. Their research concluded both groups of teachers were seeking professional development in preparing grant proposals to secure added funding. Other needs included reducing work-related stress and better managing time. Stair et al. (2019) found that both traditionally and alternatively certified agriculture teachers needed support using instructional technologies and developing online teaching resources. Additional needs for alternatively certified agriculture teachers included student motivation and managing instructional facilities. In the area of leadership development (FFA) and Supervised Agricultural Experience (SAE), alternatively certified teachers indicated a desire for Career Development Event (CDE) and Leadership Development Event (LDE) training.

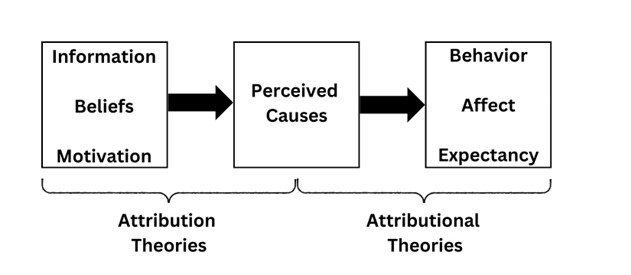

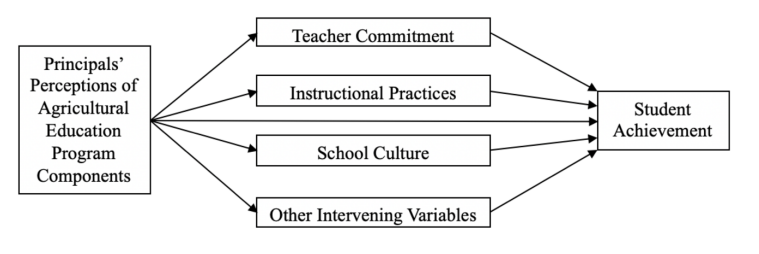

Hillison (1977) and Stair et al. (2012) used a slightly different perspective as they examined the levels of concern expressed by first-year agriculture teachers. Their research was guided by the work of Fuller (1969), Fuller and Case (1972), and Parsons and Fuller (1974). Fuller (1969) initially proposed three phases of concern: a pre-teaching phase, an early teaching phase, and a late teaching phase. This conceptualization moves across a continuum of concerns from being non-teaching specific during pre-service coursework to focusing on self during the early teaching phase and concerns about students during the late teaching phase. Later, Fuller and Case (1972) presented an expanded version of teacher concerns that included seven categories: concerns about self (non-teaching concerns), concerns about self as a teacher (where do I stand?; how adequate am I?; how do pupils feel about me? what are pupils like?), and concerns about pupils (are pupils learning what I am teaching?; are pupils learning what they need?; how can I improve myself as a teacher?). A revised three-stage model was later proposed including only concerns about self, concerns about task, and concerns about impact upon students (Conway & Clark, 2003; Parsons & Fuller, 1974).

In 1989, research conducted by Camp and Heath-Camp guided the development of the teacher proximity continuum, which helped inform the content of teacher induction programs and provided direction for additional research efforts (Joerger & Bremer, 2001). The framework was comprised of eight categories of teacher concerns and challenges, including internal, pedagogy, curriculum, program, students, peers, system, and community. Later work by Joerger and Bremer (2001) built upon the teacher proximity continuum to provide specific topics to be reinforced throughout beginning teacher programs along with a list of activities that could support the career satisfaction of early career teachers. Joerger and Bremer (2001) reinforced the critical role of various stakeholders when stating, “they can exert considerable influence in the formulation and implementation of policies, practices, and programs that contribute to optimal teaching experiences for novice educators.”( p. 15). Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) examined several educational systems worldwide to identify the established policies supporting high-quality teaching. Two such policies reinforced the importance of induction, mentoring, and professional learning. In a discussion of continuing professional development, Greiman (2010) cautioned that some induction approaches attempt to incorporate all the knowledge acquired over the lifespan of teaching, which can be overwhelming to beginning teachers. Instead, recommendations include identifying and addressing induction participants’ specific needs and pressing challenges.

Most recently, Disberger et al. (2022) proposed several suggestions for the structure and content of induction programs for beginning agriculture teachers. A three-year program was recommended and included the following topics as suggested content:

Year 1 – obtaining supplies and equipment; student management; balancing and prioritizing FFA, SAE, and classroom; agriculture content and/or delivery sources; work/life balance – new lifestyle and community

Year 2 – SAE; parent communication; isolation; evaluating additional responsibilities

Year 3 – student motivation; new ideas; communicating with the broader community; work/life balance – life transitions

To support beginning agriculture teachers in North Carolina, a 40-hour induction program is in place. The Department of Public Instruction requires agriculture teachers on a restricted license to complete the program within their first three years of employment. Those pursuing a residency-based license or provisionally certified beginning teachers may also participate based on personal interest or the recommendation of their local school. Six components are included: a fall and spring conference, a workshop at the summer Career and Technical Education conference, attendance at fall and spring teacher in-service meetings, and an experience at the State FFA Convention. The fall and spring conferences comprise most of the participation hours and consist of sessions facilitated by a team of mentor teachers, teacher educators, and state staff. Sessions are informed by previous research on concerns and professional development needs of novice teachers and include topics such as instructional planning and delivery, student engagement, supporting students with diverse needs, classroom and facility management, SAE, FFA chapter operations, and program funding.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic made a significant disruption and has had lingering effects on educational delivery. Research by McKim and Sorensen (2020) reported that agriculture teachers experienced a decline in work hours and work interference with family, indicating the reallotment of time and effort away from their work roles into their personal and family responsibilities. There was also a dramatic decrease in job satisfaction (Eck, 2021; McKim & Sorensen, 2020). Easterly et al. (2021) discussed the exhaustion experienced by teachers as they struggled to manage facilities and adjust their instructional delivery methods.

While there has been a wealth of research in agricultural education on the needs and concerns of beginning agriculture teachers and recommendations on the delivery of teacher induction programs, there was a need to conduct research specific to North Carolina. The induction program was started in 2009 and while regular evaluation has occurred, there has not been an intentional effort to identify the specific concerns and needs of participants. Additionally, with the changes in the educational landscape due to the ongoing pandemic and an increase of new teachers across the state, the findings will be valuable in informing the development of future programming. Seeing that teachers participating in the Developing Educational Leaders and Teachers of Agriculture (DELTA) program may have anywhere from one to three years of experience and come from a variety of certification pathways, it was determined that examining a broad scope of inservice needs and also providing an opportunity to capture immediate concerns would be the most appropriate.

Purpose and Research Objectives

The purpose of this study was to describe the concerns of teachers participating in the DELTA program. The following research objectives guided the study:

1. Identify DELTA teachers’ level of need for content related to SAE/FFA, program management and planning, curriculum and instruction, and teacher professional development.

2. Identify and classify categories of DELTA teachers’ self-reported concerns.

Methods

The design for this study was descriptive. The accessible population was all teachers who attended the 2022 December (N = 31) and 2023 March (N = 28) DELTA teacher in-service training. Frames were obtained through the registration platform used by the DELTA program. Duplicate participants were eliminated, creating a final target population of N = 36. Because of the small size, a census was sought. The questionnaire was shared via Qualtrics in mid-March 2023. In alignment with IRB approval, two follow-up email attempts were made to contact non-respondents. The accepting sample was n = 22, creating a final response rate of 61%.

Instrumentation

The scale data were collected using a modified version of the researcher-created instrument first developed by Roberts and Dyer (2004). The instrument sought to gather inservice needs in areas related to FFA/SAE, curriculum and instruction, program management and planning, and professional development. These items were rated on a Likert-type scale anchored as no need (1), a little need (2), a moderate need (3), a strong need (4) and a very strong need (5). For our study, we did not use the section with items related to technical agriculture as this is not content typically addressed through the DELTA program. Roberts and Dyer (2004) reported reliability for the included constructs as FFA and SAE (.88), supervision instruction and curriculum (.95), program management and planning (.95), and teacher professional development (.91). Since we removed a few items from their constructs, we ran post-hoc reliability. Reliabilities for our study are reported as follows: FFA and SAE (8 items) = .84, Curriculum and Instruction (20 items) = .97, Program Management and Planning (14 items) = .96, and Teacher Professional Development (4 items) = .95.

For the second section of our instrument, we used the open-ended response section from Stair et al. (2012). The item was “When you think about teaching, what are you concerned about? (Do not say what you think others are concerned about, but only what concerns you now.) Please be frank.” The third section gathered the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Data Analysis

The scaled items were calculated as construct grand means and individual item frequencies and percentages. We collapsed responses of very strong need and strong need into a category we titled high need. This is consistent with how Roberts and Dyer (2004) reported their data.

For the open-ended responses in section two, many respondents gave us multiple items in bullet or paragraph form. We broke the participant responses into individual items to allow for coding. We used the pre-existing codes of nonteaching, self, task, and impact (Conway & Clark, 2003; Parsons & Fuller, 1974). We coded first as individuals and then met as a research team to ensure alignment and resolve any items where there was a disagreement in coding. An example of an item coded into nonteaching included “lack of true support; people say they will help with this or that, but when it comes to it- it isn’t always true.” An example of an item coded into self was “teaching partner relationships.” An example of an item that was coded as a task concern was “classroom management.” Lastly, an example of an item coded into impact was “Are my students understanding and absorbing the information?”

There were also responses where we would have benefitted from the opportunity to follow up with participants to explore the statement. For example, one of their concerns was “PBMs.” Our state has recently implemented a performance-based measurement (PBM) assessment at the end of some agriculture courses. It is unclear from their very short response if they are concerned with understanding, organizing, teaching, being evaluated on the data, impact on students, or something else related to PBMs. Without more information, it is impossible to narrow down which teaching related concern category this brief response would fit, and was thus coded into multiple categories.

Participant Demographics

To fully interpret and apply the data, it is important to understand the characteristics of the DELTA participants. The participants were 77.3% female (n = 17), 18.2% male (n = 4), and 4.6% a third gender (n = 1). The majority of participants (81.8%) taught high school only (n = 18), and the remaining 18.2% taught middle school only (n = 4). Nine (40.9%) participants worked in one-teacher programs, ten (45.5%) worked in two-teacher programs, two (9.9%) worked in three-teacher programs, and one participant (4.6%) worked in a five-teacher program. Half (n = 11) of the participants had been enrolled in a SBAE program as a student.

All participants were in their first two years of teaching agricultural education, with 81.8% in their first year (n = 18) and 18.2% in their second year (n = 4). There was a larger range of overall teaching experience with 14 first-year teachers (63.7%), two second-year teachers (9.1%), one fourth-year teacher (4.6%), one 10-year teacher (4.6%), three 11-year teachers (13.6%) and one 13 year teacher (4.6%).

The participants ranged from 22 to 41 years old, with a median age of 27.5 and a mean age of 29. The majority of participants (86.6%) had completed a bachelor’s degree (n = 19), while the remaining participants (13.6%) had completed a master’s degree (n = 3). Of the respondents, 50.0% were working under a residency license (n = 11), 22.7% were working under a restricted license (n = 5), 13.6% were working under a professional license (n = 3), 9.1% were working under another license type (n = 2), and 4.6% did not know what kind of license they were using (n = 1).

Findings

The first objective of this study was to identify the level of needs for DELTA teachers. We addressed this objective through statements related to four constructs.

FFA and SAE

There were eight items in the FFA and SAE construct, and each was identified by participants as an area in which they needed content support. Over half of the participants identified three items as having a high need (see Table 1). These items included developing SAE opportunities (68.2%), supervising SAE programs (68.2%), and preparing the program of activities and national chapter award applications (59.1%). The overall grand mean for the FFA and SAE construct was 3.23 (SD = 0.82)

Table 1

Participants with a strong need for DELTA content related to FFA and SAE (n = 22)

| Item | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Developing supervised agricultural experience opportunities | 15 | 68.2 |

| Supervising SAE programs | 15 | 68.2 |

| Preparing program of activities and national chapter award applications | 13 | 59.1 |

| Preparing for career development events | 10 | 45.5 |

| Preparing FFA degree applications | 9 | 40.9 |

| Organizing and maintaining an alumni association | 7 | 31.8 |

| Preparing proficiency award applications | 6 | 27.3 |

| Supervising show animal SAE projects | 6 | 27.3 |

Curriculum and Instruction

The construct related to curriculum and instruction included twenty items, all of which participants indicated were needed (see Table 2). The grand mean was M = 3.21 (SD = 1.04). Half of the items were identified by at least half of the participants as having a high need by the participants. The areas with the highest need included modifying lessons for special needs and ESOL students (72.7%), managing student behavior (59.1%), and teaching in laboratory settings (59.1%). The area with the lowest need included developing a magnet program or academy (19.1%). The grand mean for the curriculum and instruction construct was 3.21 (SD = 1.04).

Table 2

Participants with a strong need for DELTA content related to Curriculum and Instruction

(n = 22)

| Item | n | f | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modifying lessons for special needs and ESOL students | 22 | 16 | 72.7 |

| Managing student behavior | 22 | 13 | 59.1 |

| Teaching in laboratory settings | 22 | 13 | 59.1 |

| Motivating students (teaching techniques and ideas) | 22 | 12 | 54.6 |

| Developing critical thinking skills in your students | 22 | 12 | 54.6 |

| Integrating state performance tests and PBMs | 22 | 12 | 54.6 |

| Teaching problem-solving and decision-making skills | 22 | 11 | 50.0 |

| Modifying curriculum and courses to attract high-quality students | 22 | 11 | 50.0 |

| Developing a core curriculum for agricultural education | 22 | 11 | 50.0 |

| Changing the curriculum to meet changes in technology | 22 | 11 | 50.0 |

| Teaching leadership concepts | 22 | 10 | 45.5 |

| Integrating science into agricultural instruction | 22 | 10 | 45.5 |

| Designing programs for non-traditional and urban students | 22 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Integrating math into agricultural instruction | 22 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Testing and assessing student performance | 22 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Integrating literacy into agricultural instruction | 21 | 9 | 40.9 |

| Using computer technology and computer applications | 22 | 8 | 36.4 |

| Understanding learning styles | 21 | 7 | 31.3 |

| Planning an effective use of block scheduling | 21 | 6 | 28.6 |

| Developing a magnet program or academy | 21 | 4 | 19.1 |

Program Management and Planning

The grand mean for the program management and planning construct was the highest of the four areas, at M = 3.34, SD = 0.98. The construct consisted of 14 items, nine of which were recognized as having a high need by participants (see Table 3). Participants’ top areas of concern included fundraising (59.1%) and writing grant proposals for external funding (54.6%).

Table 3

Participants with a strong need for DELTA content related to Program Management and Planning (n = 22)

| Item | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Fundraising | 13 | 59.1 |

| Writing grant proposals for external funding | 12 | 54.6 |

| Conducting needs assessments and surveys to assist in planning agriculture programs | 12 | 54.6 |

| Planning and maintaining a school land lab | 12 | 54.6 |

| Developing business and community relations | 12 | 54.6 |

| Completing reports for local and state administrators | 11 | 50.0 |

| Building the image of agriculture programs and courses | 11 | 50.0 |

| Recruiting and retaining quality students | 11 | 50.0 |

| Establishing a public relations program | 11 | 50.0 |

| Utilizing a local advisory committee | 10 | 45.5 |

| Building collaborative relationships | 10 | 45.5 |

| Managing learning labs | 9 | 40.9 |

| Establishing a working relationship with local media | 8 | 36.4 |

| Evaluating the local agriculture program | 7 | 31.8 |

Professional Development

The grand mean for the professional development construct was M = 3.01, SD = 1.29, the lowest of the four constructs. This construct consisted of four items, all of which were identified as having a high need by less than half of the participants (see Table 4). The areas recognized with the highest need included time management tips and techniques (45.6%) and professional growth and development (45.6%).

Table 4

Participants with a strong need for DELTA content related to Professional Development

(n = 22)

| Item | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Time management tips and techniques | 10 | 45.5 |

| Professional growth and development | 10 | 45.5 |

| Managing and reducing work-related stress | 9 | 40.9 |

| Becoming a member of the total school community | 6 | 27.3 |

For the second objective, participants provided 44 individual concerns when asked, “When you think about teaching, what are you concerned about?” We coded the open-ended statements into the four categories of concerns. Due to the vague nature of some statements, we chose to have some statements recognized in multiple categories of concerns, increasing the total number of concerns to forty-nine (see Table 5). Task concerns (51.0%) and self-concerns (28.6%) were where participants’ highest levels of concern were concentrated.

Table 5

Levels of concerns

| Category of Concern | Number of Concerns | % |

|---|---|---|

| Task | 25 | 51.0 |

| Self | 14 | 28.6 |

| Impact | 7 | 14.3 |

| Nonteaching | 3 | 6.1 |

Task concerns were the most prevalent among the participants and revolved around items that required teacher time or decisions. Examples of these task concerns included, “I also love to be outside, but finding labs and activities for students to do outside can be SUPER time-consuming and expensive in some cases,” “control of students during lab situations,” and “the pressures administration puts on a beginning agriculture teacher that have nothing to do with the job they were hired to do.” Examples of self-concerns were aligned with personal experience or preparation and included items such as “Safety. I have been assaulted twice this year,” “I am concerned about the longevity of this career. Between teaching classes, FFA, maintaining lab area (greenhouses, barns, livestock, etc.), engaging with and serving the community, as well as any additional responsibilities given to teachers locally at their school, it is difficult to imagine surviving year one, much less 10, 20, or 30 years,” and “I’m concerned about the way my students treat me and the lack of respect I receive. I don’t think anyone has taught them how to act or treat others. I don’t know how to train someone at this age (high school) to be respectful.” and “Time management. I feel pressured from other chapters to push myself. I know that jealousy is the thief of joy, and I am new and starting out.” Multiple vague responses from participants fell into both the task and impact categories. Examples of these items included “reaching the students that are unmotivated to learn,” and “I teach at an urban low-income school. Many of my students have transportation and/or financial issues that make it very difficult to participate in FFA or SAE activities. I am concerned about giving these students quality, hands-on learning experiences in the classroom.”

Conclusions, Implications, and Recommendations

In line with Greiman’s (2010) recommendations, this study’s conclusions will be valuable in providing a targeted approach to teacher induction. The highest overall area of need was related to program management and planning including items related to fundraising, grant writing, managing laboratory facilities, and connecting and managing community partnerships. The lowest overall area of need was teacher professional development, which may be related to the fact that these teachers received this instrument because of their attendance at a professional development offering.

SAE was the highest need area among the FFA and SAE items. DiBenedetto et al. (2018) found that this need appeared in multiple teacher needs assessments from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Disberger et al. (2022) also reported teachers sought support in implementing SAE. There is an opportunity here as the national re-launch of SAE for All is driving SAE-related professional development, not only at conferences like DELTA, but also at the state’s fall in-service teacher meetings and the statewide summer conference sessions. Across the state, teachers are being encouraged to integrate foundational SAEs into their courses and provided with practical resources.

ESOL and special needs modifications were the highest identified area in curriculum and instruction. DiBenedetto et al. (2018) determined this was an emerging need that began to appear in the 2000s. While Stair et al. (2010) indicated that teachers were confident in accommodating students with specific needs, they disagreed that they received helpful preparation through in-service opportunities. This finding was supported by follow-up research conducted by Stair et al. (2016). As such, trying to keep current on strategies and approaches for supporting students with special needs and delivering relevant professional development is critically important. Incorporating in-service offerings delivered by certified ESE and/or ESOL teachers might also be beneficial.

Motivating students showed up on both the open-ended responses and were rated highly on the Likert-type scale. This aligns with Roberts and Dyer (2004) who found student motivation to be the third highest need item on the curriculum and instructional items. Our current DELTA curriculum does address motivating students but tends to talk about strategies for hands-on learning and applied and/or lab-based activities which teachers indicated can be limited by budgets. Fundraising and grant writing were both rated highly on the Likert-type scale but when combined with the understanding offered by the open-ended data, the need appeared to be less about wanting ideas for fundraising or grant sources and more about the need for funding to provide opportunities for hands-on learning and to engage in opportunities. This aligns with a needs assessment of Oregon teachers conducted by Sorensen et al. (2014), in which grant writing was the highest overall need for induction phase teachers.

Managing student behavior showed up on both the open-ended feedback and the Likert-type scale, which aligns with the quantitative findings of Stair et al. (2012). The open-ended responses ranged from “classroom management” and “behavior issues” to the more specific “I’m concerned about the way my students treat me and the lack of respect I receive. I don’t think anyone has taught them how to act or treat others. I don’t know how to train someone at this age (high school) to be respectful.” We do spend time in the DELTA curriculum (fall DELTA conference and summer new teacher workshop) on managing student behavior. Still, it is a critical component for teachers to feel in charge of their own learning environment. Continued emphasis on this should include not only traditional classroom management content, but ideas for managing students outdoors and in other agricultural labs like greenhouses, shops, and animal handling facilities. We also need to continue to offer student engagement strategies and reinforce that engaged students are less likely to demonstrate behavior that needs to be managed by the teacher.

There were six participants with previous teaching experience outside of agricultural education, which may help explain why ag education-specific items rose to the top of the list. If teachers have 10 or 11 years of teaching experience in history or English or middle school science, they are likely to be confident in teaching and delivery as well as their fit in the school system, but the items that would be new include SAE, FFA and other program planning related items. Perhaps a further study could be conducted to understand this unique group more fully within the state who are moving to agricultural education with prior experience in teaching other disciplines.

Roberts and Dyer (2004) found one of the high needs for their participants was in the area of “using computer technology and computer applications,” but this finding did not hold true for our respondents. This could be due to the ubiquity of technology in teaching now compared to 2004 or the changing demographics of the teachers in the study and their native status to technology. It could also be that this study occurred after the 2022 peak of the COVID-19 pandemic when many participants may have been forced to learn educational technology.

Table 6

Comparison of construct grand means in current study to Roberts and Dyer (2004)

| Construct | DELTA participants (2023) grand means | Roberts & Dyer (2004) grand means for Alternative licensure |

|---|---|---|

| FFA & SAE | M = 3.23, SD = 0.82 | M = 3.057, SD = 0.92 |

| Instruction and Curriculum | M = 3.21, SD = 1.04 | M = 2.98, SD = 0.87 |

| Program Management & Planning | M = 3.34, SD = 0.98 | M = 3.10, SD = 1.02 |

| Teacher Professional Development | M = 3.01, SD = 1.29 | M = 3.21, SD = 1.31 |

Open-ended concerns responses were heavily task-focused. This aligns with the Fuller’s (1969) phases of teacher concerns. Fuller indicated that preservice teachers tend to focus on non-teaching or self-concerns while those in late careers tend to focus on impact. These DELTA teachers are almost all early in their teaching careers and they all are early in their agriculture teaching careers.

A number of open-ended responses addressed administration pressure or administrative help indicating a concern related to the outside influence on their job. The DELTA curriculum does integrate a few items on communicating with administration but has very little control over the local school environment.

A number of participants had questions about longevity related to the workload, the salary, the profession of teaching, as well as the past performance of their current school’s program in regard to teacher retention. These concerns are valid. The DELTA curriculum is presented in part by a team of teacher educators and state staff who are well aware of the challenges that these teachers are facing. Still, the presentation team also includes 5-6 current classroom teachers who have navigated the long-term realities of the classroom agriculture teacher. We currently do not expressly tackle these concerns within the curriculum but should consider how to bring them forward.

One interesting self-concern that surfaced in the open-ended responses was related to teacher safety. One teacher indicated they had been assaulted twice during the school year so far (data were collected in March). While this is outside of the programming content within the DELTA program, administration, policymakers, and teacher educators need to be aware of the environment in which teachers are expected to carry out their jobs.

Recommendations for Future Research

Longitudinal research has concluded that the focus of beginning teachers’ needs changes over the course of the year. For example, Disberger et al. (2022) reported that during the first half of the academic year, teachers indicated concern with planning for the National FFA Convention as compared to the emphasis on FFA fundraising activities during the second half of the year. A similar phenomenon occurred regarding student management, technical content knowledge, and instructional methods. Conway and Clark (2003) also noted a more dynamic interpretation of the concerns model in which teacher concerns may move outward but can return to a more inward focus. While this inquiry provides key findings, it is specific to needs and concerns at one point in time. It is recommended that this research be replicated at the three teacher workshops to see if there is any change over year.

References

Andreatta, R. R. (2023). How agricultural educators are drawn to their career path: An examination of agricultural educators in three states [Unpublished thesis]. North Carolina State University.

Birkenholz, R. J., & Harbstreit, S. R. (1987). Analysis of the inservice needs of beginning vocational agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 28(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.5032/jaatea.1987.01041

Camp, W. G., & Heath-Camp, B. (1989). Induction detractors of beginning vocational teachers with and without teacher education. ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED328747.pdf

Conway, P. F., & Clark, C. M. (2003). The journey inward and outward: A reexamination of Fuller’s concerns–based model of teacher development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(5), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742–051X(03)00046–5

Darling-Hammond, L., Burns, D., Campbell, C., Goodwin, A. L., Hammerness, K., Low, E. L., McIntyre, A., Sato., M., & Zeichner, K. (2017). Empowered educators: How high-performing systems shape teaching quality around the work. Jossey-Bass.

DiBenedetto, C. A., Willis, V. C., & Barrick, R. K. (2018). Needs assessments for school-based agricultural education teachers: A review of literature. Journal of Agricultural Education, 59(4), 52–71. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2018.04052

Disberger, B., Washburn, S. G., Hock, G., & Ulmer, J. (2022). Induction programs for beginning agriculture teachers: Research-based recommendations on program structure and content. Journal of Agricultural Education, 63(1), 132–148. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2022.01132

Easterly, R. G., Humphrey, K., & Roberts, G. (2021). Exploring how COVID-19 impacted selected school-based agricultural education teachers in the United States. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v2i1.79

Eck, C. (2021). Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on school-based agricultural education teachers in South Carolina. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 2(2), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v2i2.117

Fuller, F. F. (1969). Concerns of teachers: A developmental conceptualization. American Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312006002207

Fuller, F. F., & Case, C. (1972). A manual for scoring the teacher concerns statement (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: Texas University Research and Development Center for Teacher Education. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED079361.pdf

Garton, B. L., & Chung, N. (1996). The inservice needs of beginning teachers of agriculture as perceived by beginning teachers, teacher educators, and state supervisors. Journal of Agricultural Education, 37(3), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1996.03052

Greiman, B. C. (2010). What can be done to support early career teachers? The Agricultural Education Magazine, 82(6), 4–5, 10. https://www.naae.org/profdevelopment/magazine/archive_issues/Volume82/2010_05-06.pdf

Hillison, J. (1987). Agricultural teacher education preceding the Smith-Hughes Act. Journal of Agricultural Education, 28(2), 8–17. https://doi.org/10.5032/jaatea.1987.02008

Hillison, J. (1977). The concerns of agricultural education pre-service students and first year teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 18(3), 33–39. https://doi.org/10.5032/jaatea.1977.03033

Joerger, R. M., & Bremer, C. D. (2001). Teacher induction programs: A strategy for improving the professional experience of beginning career and technical education teachers. (ED458436). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED458436.pdf

Korte, D. S., Mott, R., Keating, K. H., & Simonsen, J. C. (2020). Choosing a life of impact: A grounded theory approach to describe the career choice of becoming a high school agriculture teacher. Journal of Human Sciences and Extension, 8(2), 237–259. https://doi.org/10.54718/MUPN5082

Lawver, R. G., & Torres, R. M. (2012). An analysis of post-secondary agricultural education students’ choice to teach. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(2), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.02028

McKim, A. J., & Sorensen, T. J. (2020). Agricultural educators and the pandemic: An evaluation of work and life variables. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(4), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.04214

Mundt, J. (1991). The induction year – A naturalistic study of beginning secondary teachers of agriculture in Idaho. Journal of Agricultural Education, 32(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1991.01018

National Association of Agricultural Educators. (2023). National teach AG campaign. https://www.naae.org/teachag/index.cfm

Parsons, J. S., & Fuller, F. F. (1974, April). Concerns of teachers: Recent research on two assessment instruments. [Paper presentation]. American Educational Research Association 59th Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, United States.

Roberts, T. G., & Dyer, J. E. (2004). Inservice needs of traditionally and alternatively certified agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(4), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2004.04082

Smith, A. R., Foster, D. D., & Lawver, R. G. (2022). National agricultural education supply and demand study, 2021 executive summary. http://aaaeonline.org/Resources/Documents/NSD 2021Summary.pdf

Sorensen, T. J., Lambert, M. D., & McKim, A. J. (2014). Examining Oregon agriculture teachers’ professional development needs by career phase. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(5), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2014.05140

Stair, K. S., Blackburn, J. J., Bunch, J. C., Blanchard, L., Cater, M., & Fox, J. (2016). Perceptions and educational strategies of Louisiana agricultural education teachers when working with students with special needs. Journal of Youth Development, 11(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2016.433

Stair, K., Figland, W., Blackburn, J., & Smith, E. (2019). Describing the differences in the professional development needs of traditionally and alternatively certified agriculture teachers in Louisiana. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(3), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.03262

Stair, K. S., Moore, G. E., Wilson, B., Croom, B., & Jayaratne, K. S. U. (2010). Identifying confidence levels and instructional strategies of high school agricultural education teachers when working with students with special needs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 51(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2010.02090

Stair, K. S., Warner, W. J., & Moore, G. E. (2012). Identifying concerns of preservice and inservice teachers in agricultural education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(2), 153–164. https://www.doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.02153

Talbert, B. A., Camp, W. G., & Heath-Camp, B. (1994). A year in the lives of three beginning agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 35(2), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1994.02031

Washburn, S. G., King, B. O., Garton, B. L., & Harbstreit, S. R. (2001). A comparison of the professional development needs of Kansas and Missouri teachers of agriculture. In Proceedings of the 28th National Agricultural Education Research Conference, 28(1), 396–408.