Kevan W. Lamm, University of Georgia, kl@uga.edu

Hannah S. Carter, University of Maine, hcarter@maine.edu

Alexa J. Lamm, University of Georgia, alamm@uga.edu

Nekeisha Randall, University of Georgia, nlr22@uga.edu

Abstract

Organizational leadership is the foundation of success for mission-driven systems of all sizes. Leading an organization in today’s society requires adaptive and relational skills that meet the demands of complex and changing environments. There is a need for a theoretically-based model specifically designed for organizational leadership. The purpose of this article was to address this gap by proposing a model of organizational leadership that expands upon previous recommendations in the literature and specifically identifies 11 areas synthesized from previous taxonomic recommendations. The organizational leadership conceptual model should provide agricultural leadership educators with a robust framework for the development of adaptive leaders and contextually appropriate leadership curriculum.

Introduction

Effectiveness in the area of organizational leadership is vital to every level of an organization and has implications for an organization’s culture, finances, daily operations, and strategic plans (Society for Human Resource Management, 2015). As noted by Deloitte’s Global Human Capital Trends Survey (Deloitte, n.d.) taken by thousands of human resource and business leaders from all over the world, the dominance and importance of organizational leadership is an increasingly prevailing trend each year. Based on research shared from Deloitte’s 2014 survey findings, “Leadership remains the No. 1 talent issue facing organizations around the world” (Canwell, Dongrie, Neveras, & Stockton, 2014). From 2013-2018, organizational leadership was highlighted as a top area of challenge and opportunity in every survey report Deloitte produced, at times being rated by 86% of world-wide respondents as an important or urgent topic (Canwell et al., 2014).

Annual research findings connect organizational leadership trends to the development of a multi-generational workplace, adaptation to a fast-changing society, improvement of internal leadership development pipelines, success of digital intelligence, and collaborative efforts with and among leaders (Deloitte, n.d.). According to the Society for Human Resource Management, human resource leaders currently view the development of the next generation of organizational leaders as a top human capital challenge and will continue to do so through (and possibly beyond) the year 2025 (Society for Human Resource Management, 2015). Today’s organizations “…have arrived at a turning point in the evolutionary arc of leadership, where yesterday’s theories struggle to keep pace with the velocity of today’s disruptive marketplace” (Pelster, 2013). Better organizational leadership theories are needed to assist leaders in adapting to trends such as technology advancements and workplace diversity (Abbatiello, Knight, Philpot, & Roy, 2017), as well as in the exploration of research areas such as, “how organizational design can shape and leverage leadership development” (Törnblom, 2018).

Within the organizational context a relevant consideration is the distinction between leadership and management. Abraham Zaleznik (1977) explored the differences between the two in his work finding managers tend to adopt a more impersonal approach with greater focus on rationality and control. Typically, organizations use managers to ensure proper execution of tasks and goals, whereas leaders may or may not be in a management role per se, therefore the two roles are not synonymous (Bass, 2008). Accordingly, the intent of the present work is not to focus on management, but rather to focus on leadership, whether through formal or informal means. According to Lunenburg (2011), “In today’s dynamic workplace [organizations], we need leaders to challenge the status quo and to inspire and persuade organization members” (p. 3). This sentiment is similar to Bennis (1989) who previously stated,

To survive in the twenty-first century, we are going to need a new generation of leaders—leaders, not managers. The distinction is an important one. Leaders conquer the context—the volatile, turbulent, ambiguous surroundings that sometimes seem to conspire against us and will surely suffocate us if we let them—while managers surrender to it (p. 7).

Therefore, the need to focus on the skills necessary for leadership success within organizational contexts is important. However, the organizational context is also important to recognize as the environment within which the leadership occurs (Lunenburg, 2011).

According to the 2016-2020 American Association for Agricultural Education (AAAE) National Research Agenda, priority area five identifies the need for efficient and effective agricultural education programs (Roberts, Harder, & Brashears, 2016). This article presents a theory-based conceptual model of organizational leadership based on a comprehensive review and synthesis of existing leadership literature. The resulting model should provide an appropriate curriculum framework to enhance the transfer of learning in agricultural leadership education settings.

Theoretical Framework

From a systems theory perspective, organizations have a structure; however, the structure has been described as artificial insofar as they are constructs bound together through psychological, rather than physical, bonds (Katz & Kahn, 1977). According to Robbins and Judge (2009), an organization has been defined as, “a consciously coordinated social unit, composed of two or more people, that functions on a relatively continuous basis to achieve a common goal or set of goals” (p. 7). “Organizations emerge because individuals can achieve goals through collective action that could not be attained by individuals working alone” (Fleishman et al., 1991). Additionally, Bass (2008) indicated, “leadership is often regarded as the single most critical factor in the success or failure of [organizations]” (p. 11). Based on the ubiquity of organizations, a critical analysis of the leadership characteristics associated with organizational outcomes has been warranted (Bass, 2008).

Previous research has found leadership to be strongly related to organizational performance. For example, Day and Lord (1988) analyzed organizational performance when organizations experienced changes in executive leadership; when controlling for other factors, leadership accounted for up to 45% of the difference in performance. Similar performance differentials were identified when industrial organizations were retrospectively analyzed relative to leadership. Specifically, high performing leaders produced better organizational financial results than lower performing peers (Barrick, Day, Lord, & Alexander, 1991). Thus, organizational leadership makes a difference and is necessary for goal progression. Conceptualization of organizational leadership can involve the timeless aspects of: properly acquiring and handling information, identifying needs, planning, taking risks, inspiring others, obtaining and maintaining resources, monitoring the environment, and providing feedback.

Acquiring information: Antecedents for organizational emergence are environmental pressures or requirements for a given situation (Katz & Kahn, 1977). Consequently, a primary responsibility of an organizational leader has been to acquire information germane to the organization’s purpose or situation (Fleishman et al., 1991). Therefore, one of the primary themes within the literature has been that effective leaders have an orientation toward information. Specifically, effective leaders have been shown to collect information and intelligence (Olmstead, Baranick, & Elder, 1978; Olmstead, Cleary, Lackey, & Salter, 1976; Roby, 1961), seek information (Metcalfe, 1984), and process information (Olmstead, Cleary, Lackey, & Salter, 1976).

Although effective leaders typically have a level of expertise (Haiman, 1951; Krech & Crutchfield, 1948; Wilson, O’Hare, & Shipper, 1990) knowledge (Williams, 1956), and wisdom (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006) necessary to lead within an organizational context, previous experiences and knowledge (Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Jacobs, & Fleishman, 2000) are not always sufficient. Specifically, higher performing leaders have been shown to have an awareness for situational needs, such as information acquisition (Berkowitz, 1953; Greenleaf, 1970). Subsequently, leaders have been found to take needed action based on the information they acquire (McGrath, 1964; Winter, 1978). One of the primary channels that effective leaders use to acquire information has been through interacting with others (Bennett, 1971; Bowers & Seashore, 1972; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Williams, 1956). Specifically, effective leaders have used networking (Senge, 1995; Yukl, 1998), social skills (Bell, Hill, & Wright, 1961; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Olmstead et al., 1973), and relationship cultivation (Hemphill, 1950; Metcalfe, 1984; Sayles, 1981) to gather information.

Clarifying, organizing, and evaluating information: After leaders have acquired information, effective leaders have been shown to clarify, organize, and evaluate information accordingly (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl, Gordon, & Taber, 2002). For example, effective leaders have been shown to handle (Morse & Wagner, 1978), process (Hitt, Middlemist, & Mathis, 1983), and clarify information as necessary (Gross, 1961; Wilson et al., 1990; Yukl, 1998). One strategy effective leaders have used to clarify information has been through negotiation (Fine, 1977; Kessing & Kessing, 1956; Mahoney, Jerdee, & Carroll, 1965; Miller, 1974; Sayles, 1981), which also assists with identifying and resolving information deficiencies.

When leaders feel they have acquired and clarified information to a satisfactory level, effective leaders have been shown to analyze the information accordingly (Bennett, 1971; Fine, 1977; Lord & Maher, 1993; Olmstead et al., 1976). One of the primary means that effective leaders have been shown to analyze and organize information has been through their technical, or functional, competence (Bradford & Cohen, 1984; Clement & Ayres, 1976; Helme, 1974 Heifetz, 1994; Senge, 1995; Showel & Peterson, 1958; Katz, 1955).

To evaluate information in an appropriate manner, effective leaders have been shown to use ethical (Clement & Ayres, 1976; Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, 2008; Whitehead, 2009), moral (Sendjaya, Sarros, & Santora, 2008; Walumbwa, Avolio, Gardner, Wernsing, & Peterson, 2008), and values-based approaches (George, 2003; Heifetz, 1994).

Identifying needs and requirements: Clarifying, organizing, and evaluating information assists with identifying needs and requirements, one of the primary areas where the most effective organizational leaders have been shown to demonstrate leadership capabilities (Fleishman et al., 1991). Insights into the flow of work (Sayles, 1981), and an ability to sustain (Schein, 1995) and conduct work (Bradford & Cohen, 1984), have been associated with an ability to identify appropriate needs of the organization and requirements to fulfill identified needs. Demonstrating proficiency in this area helps organizational leaders make decisions, which is a skill prominent in organizational leadership literature (Clement & Ayres, 1976; Hitt et al., 1983; Jacobs, 1983; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Olmstead et al., 1973; Olmstead et al., 1975; Olmstead et al., 1978; Page, 1985; Williams, 1956). When leaders decide (Bennett, 1971; Mintzberg, 1973; Suttel & Spector, 1955) or choose appropriate means (Gross, 1961), they provide the necessary direction to the organization (Farr, 1982). This direction is based on needs, and tasks to fulfill them, in an effort to make individuals and the whole organization more effective. Furthermore, requirements put forth to fulfill organizational needs can evolve into organizational standards.

Based on systems theory, an antecedent for organizations to exist has been through shared expectations and standards (Katz & Kahn, 1977). Effective leaders have been shown to establish standards to facilitate the implementation of their decisions, and subsequently the fulfillment of the requirements they set forth for others to follow (MacKenzie, 1969; Nealy & Fiedler, 1968). For example, leaders have been shown to establish standards of excellence (Larson & LaFasto, 1989), set guidelines (Metcalfe, 1984), and set procedures (MacKenzie, 1969; Metcalfe, 1984). Effective leaders have been shown to use power and influence techniques to facilitate the adoption of their decisions and standards (Bell et al., 1961; Bonjean & Olson, 1964; Hemphill, 1959; Terry, 1993).

Planning and coordinating: Within the literature, one of the most recurrent themes has been that effective leaders plan and coordinate activities (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). Numerous authors have described the planning aspect of organizational leadership (e.g. Bennett, 1971; Clement & Ayres, 1976; Davis, 1951; Farr, 1982; Hitt et al., 1983; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Koontz, O’Donnell, & Weihrich, 1958; Olmstead et al., 1978; Page, 1985; Showel & Peterson, 1958; Schermerhorn, Hunt, & Osborn, 1982; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl, 1998; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), including planning and allocating resources (Dowell & Wexley, 1978; Kraut, Pedigo, McKenna, & Dunnette, 1989) and methods planning (Stogdill, Wherry, & Jaynes, 1953).

The coordination aspects of effective organizational leadership have also been well established in the literature (e.g. Berkowitz, 1953; Kraut et al., 1989; Mahoney et al., 1965; Nealy & Fiedler, 1968; Olmstead et al., 1978; Page, 1985; Tornow & Pinto, 1976). Effective leaders have been shown to improve coordination through sufficient organization (Davis, 1951; Hitt et al., 1983; Koontz et al., 1958; MacKenzie, 1969; Morse & Wagner, 1978; Schermerhorn et al., 1982; Williams, 1956; Wofford, 1967), ordering (Suttel & Spector, 1955; Wilson et al., 1990), facilitation (Har-Evan, 1992; Quinn, Dixit, & Faerman, 1987; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), cooperation (Bonjean & Olson, 1964; Helme, 1974; Larson & LaFasto, 1989; Misumi, 1985; Wells, 1997; Winter, 1978), influence (Bell et al., 1961; Bonjean & Olson, 1964; Stogdill, Goode, & Day, 1965; Winter, 1978), tolerance (Stogdill, Goode, & Day, 1962; Stogdill et al., 1965), and environmental awareness (Morse & Wagner, 1978; Mumford et al., 2000).

To effectively lead within organizations, specifically as it has related to planning and coordinating, individuals have needed to act as change agents (Barnard, 1946; Gross, 1961; Haiman, 1951; Hook, 1943; Javidan & Dastmalchian, 1993; Leavitt, 1986; Paige, 1977; Tannenbaum & Schmidt, 1958; Schein, 1995) in combination with the appropriate amount of assertiveness (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004). Along with creating the conditions necessary to be successful (McGrath, 1964), effective leaders have been shown to be both directive (Coffin, 1944; Hersey & Blanchard, 1969; Hitt et al., 1983; House & Mitchell, 1974; MacKenzie, 1969; Schermerhorn et al., 1982) and political (Beckhard, 1995; Birnbaum, 1988; Bolman & Deal, 1991; Cribbin, 1981; Miller, 1973; Shrivastava & Nachman, 1989).

Synthesizing the myriad of functions within a planning and coordinating framework, the most effective managers have been referred to as multispecialists (Mahoney et al., 1965). These super-leaders (Manz & Sims, 1993) span boundaries (Hitt et al., 1983), align the organization and the environment (Van Wart, 2003), address challenges (Sayles, 1981; Tornow & Pinto, 1976), and provide results (Van Wart, 2003).

Risk taking: Effective leaders have been shown to have a propensity for taking risks; specifically, taking the steps necessary to move from plans to action (Conger & Kanungo, 1998; Rothschild, 1993; Yukl et al., 2002). A willingness to challenge existing processes (Kouzes & Posner, 2002), innovate (Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), and act in a revolutionary manner have been associated with effective leaders (Paige, 1977). Additionally, high performing leaders have also been shown to engage in intellectual stimulation with followers, whereby they encourage thinking that does not necessarily confirm to established norms (Bass & Avolio, 1990; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990).

Visioning and inspiring: Once a leader has identified the appropriate plan of action, and has taken a risk in deciding to act, a next step has been to develop a vision for the desired outcome in order to effectively inspire the organization to action (Yukl et al., 2002); thus effective leaders have used goals extensively. For example, to cast vision and promote inspiration, effective leaders have been shown to define (Bass, 1981; Gross, 1961; Helme, 1974; Miller, 1973; Selznick, 1957), set (Barnard, 1946; Farr, 1982; MacKenzie, 1969; Oldham, 1976; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Winter, 1978; Wofford, 1967; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), articulate (House, 1977), administer (Gross, 1961), and explain goals (Bass, 1981). Organizational leaders also help individuals feel connected to goals (Kirk & Shutte, 2004), as well as help foster the acceptance of group goals (Podsakoff et al., 1990). Furthermore, leaders have been shown to apply goal pressure (Wilson et al., 1990) and goal emphasis (Bowers & Seashore, 1972) to bring about congruence (Roby, 1961) and to ultimately attain goals (Helme, 1974).

One method effective leaders have used to translate goals into motivation has been through articulating a vision (Conger & Kanungo, 1998; Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005; Podsakoff et al., 1990). Visionary leaders (Manz & Sims, 1993; Wells, 1997) have been shown to use their foresight (Greenleaf, 1970; McGrath, 1964; Stogdill et al., 1962), conceptual ability (Greenleaf, 1970; Katz, 1955; Liden et al., 2008; Winter, 1978), convictions (Beckhard, 1995), and audience awareness (Hofstede, 1980; House et al., 2004) to appropriately motivate and inspire their organizations. Consequently, organizations have typically come to view such leaders as effective (Laub, 1999; Lord & Maher, 1991; Olmstead et al., 1973; Wofford, 1967).

According to the literature, appropriate goals have been shown to result in a sense of purpose (George, 2003; House & Mitchell, 1974; Pigg, 1999; Schein, 1995; Terry, 1993) and mission for the organization (Helme, 1971; Terry, 1993). Furthermore, purpose and mission have been shown to be related to organizational motivation (Gross, 1961; Helme, 1974; House, 1977; Koontz et al., 1958; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Morse & Wagner, 1978; Mumford et al., 2000; Olmstead et al., 1973) and inspiration (Kouzes & Posner, 2002; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979; Yukl, Wall, & Lepsinger, 1990). For example, effective leaders have been shown to encourage the heart of followers (Kouzes & Posner, 2002) and provide inspirational motivation (Bass & Avolio, 1990) by having high performance expectations (Podsakoff et al., 1990). These actions have been associated with a sense of meaning and fulfillment (Terry, 1993) as well as hope and optimism (Luthans & Avolio, 2003) within the organization.

Communicating information: Although providing a vision and inspiration for an organization has been found to be necessary for effective leadership, it has also been found to be insufficient. To complement their strategies for motivation, effective leaders have been shown to be highly adept at communicating information (Fleishman et al., 1991). Communication competence has been identified in multiple ways within the literature. For example, effective leaders must be able to communicate generally (Clement & Ayres, 1976; Helme, 1974; Jacobs, 1983; MacKenzie, 1969; Olmstead et al., 1978; Olmstead et al., 1973; Stogdill & Shartle, 1955), communicate up (Hemphill, 1950; Wilson et al., 1990), communicate down (Hemphill, 1950; Jacobs, 1983; Prien, 1963), maintain communication capability and flow (Jacobs, 1983; Olmstead et al., 1976), and communicate for implementation (Farr, 1982; Jacobs, 1983; Leavitt, 1986).

Communication has also been associated with information dissemination (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Olmstead et al., 1976; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), exchanging information (Fine, 1977; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984), and organizational collaboration (Larson & LaFasto, 1989). Leaders who communicate through discussion (Haiman, 1951), participation (Metcalfe, 1984), and collaborative partnerships (Israel et al., 1998) have been shown to promote group decision making (Miller, 1973).

Obtaining material and personnel resources: Communicating information is often complemented by the need to obtain the material and personnel resources necessary to achieve identified goals (Fleishman et al., 1991). For example, effective leaders have been found to be more adept at obtaining and managing personnel resources, including such functions as human resources (Bolman & Deal, 1991; Hemphill, 1959; Stogdill et al., 1953), selection and placement (Gilbert, 1975; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; MacKenzie, 1969; Mintzberg, 1973; Nealy & Fiedler, 1968; Oldham, 1976; Prien 1963; Schermerhorn et al., 1982), and leader-member relations (Dowell & Wexley, 1978; Fiedler, 1967; Helme, 1971; Showel & Peterson, 1958).

The ability to obtain material resources may be subsumed within the structure of an organization (Fleishman et al., 1991). For example, effective leaders have been found to focus on the structural aspects of organizations (Bolman & Deal, 1991; Terry, 1993), including the inducement, interpretation, and use of structure (Katz & Kahn, 1977). Effective leaders have also been found to be appropriately task-oriented with a prominent focus on structure (Blake & Mouton, 1964; Fleishman, 1953; Gross, 1961; Halpin & Winer, 1957; Olmstead, Lackey, & Christenson, 1975; Stogdill et al., 1962; Winter, 1978) and sensitivity to outside pressures (Bass & Farrow, 1977).

Utilizing and monitoring material and personnel resources: After material and personnel resources have been obtained, effective leaders have been shown to direct their efforts toward utilizing and monitoring those resources (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). From a utilization perspective, effective leaders have been shown to focus on production (Halpin & Winer, 1957; Hemphill, 1950, Nealy & Fiedler, 1968; Stogdill et al., 1962; Stogdill et al., 1965), work facilitation (Bowers & Seashore, 1972; Wilson et al., 1990), performance (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 1993; Larson & LaFasto, 1989; Reaser, Vaughan, & Kriner, 1974; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Wofford, 1971; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), and administration (Katz & Kahn, 1966; Manz & Sims, 1993; Olmstead et al., 1973; Stogdill et al., 1962; Stogdill et al., 1953). These functions have been shown to require unit record keeping (Elliott, Harden, Giesler, Scott, & Euske, 1979), compiling records and reports (Dowell & Wexley, 1978), and processing paper work (Luthans & Lockwood, 1984).

To further maximize resource utilization, effective leaders have been shown to be resourceful (Helme, 1971; Israel et al., 1998; Terry, 1993), competitive (Hemphill, Siegel, & Westie, 1951; Miller, 1973), and time-oriented (Olmstead et al., 1978; Wilson et al., 1990) with an ability to integrate knowledge (Cribbin, 1981; Hemphill, 1950; Stogdill et al., 1962; Stogdill & Shartle, 1955) and provide instruction to improve performance (Fine, 1977; Kraut et al., 1989; Olmstead et al., 1976; Suttel & Spector, 1955). Additionally, effective leaders have been shown to manage conflict within the organization (Krech & Crutchfield, 1948; Reddin, 1977; Selznick, 1957; Stogdill et al., 1962), providing clarity when needed (Bass & Farrow, 1977; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979) to mitigate future conflict and simultaneously attend to morale issues (Helme, 1974; Sayles, 1981).

Leaders have also been shown to effectively use rewards to maximize utilization (Bass, 1981; MacKenzie, 1969; Miller, 1973; Oldham, 1976; Olmstead et al., 1975; Sayles, 1981; Winter, 1978; Yukl, 1998). Rewards have sometimes been allocated contingent upon performance (Bass & Avolio, 1990), or may be meted out with punishments (Krech & Crutchfield, 1948; Showel & Peterson, 1958); effective leaders have been shown to administer discipline (Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979) to address utilization impediments.

From a monitoring perspective, effective leaders have been shown to employ numerous approaches. For example, leaders have been shown to monitor in general (McGrath, 1964; Miller, 1973; Yukl, 1998; Yukl et al., 1990), monitor indicators (Page, 1985), monitor operations (Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979), monitor the environment (Kraut et al., 1989), and monitor performance and results (Komaki, Zlotnick, & Jensen, 1986; Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Winter, 1978). One of the primary mechanisms leaders have been shown to monitor personnel and materials has been through supervision (Clement & Ayres, 1976; Coffin, 1944; Hemphill, 1959; Mahoney et al., 1965; Miller, 1973; Olmstead et al., 1976; Page, 1985; Prien, 1963; Tornow & Pinto, 1976).

Based on their ability to obtain the necessary monitoring insights, effective leaders have been shown to evaluate their findings (Elliott et al., 1979; Mahoney et al., 1965; Metcalfe, 1984; Stogdill et al., 1953). This process has been shown to include collecting the necessary information (Komaki et al., 1986) as well as defining the evaluation criteria (Bass, 1981). One of the primary mechanisms that leaders have been shown to effectively evaluate data has been through their control of details (Wilson et al., 1990), materials and supplies (Nealy & Fiedler, 1968), activities (Davis, 1951), relationships (Krech & Crutchfield, 1948), and processes (Hemphill et al., 1951). Through the myriad of control conditions (Hitt et al., 1983; Koontz et al., 1958; Schermerhorn et al., 1982; Wofford, 1967) effective leaders have been shown to have a stabilizing effect across the monitoring process (Jacobs, 1983).

Maintaining material resources: One of the distinctions between organizational and non-organizational leadership has been a specific focus on materials, or the means through which an organization operates (Fleishman et al., 1991). Specifically, effective leaders have been found to have an orientation toward cost control (Hemphill, 1959; Nealy & Fiedler, 1968; Tornow & Pinto, 1976), budgeting (Barnard, 1946; MacKenzie, 1969), reporting (MacKenzie, 1969), and process oversight (Bennett, 1971; Prien, 1963). Additionally, a prominent theme within the literature was that effective leaders have tended to focus on maintenance of equipment (Dowell & Wexley, 1978), supplies (Elliott et al., 1979), and services (Stogdill et al., 1953).

External monitoring, feedback, and control: In addition to monitoring materials and personnel from an operational perspective, effective organizational leaders have been shown to actively monitor the external environment, as well as to the provide the appropriate feedback and control back to the organization (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). A theme within the literature has been that effective leaders tend to be focused on performance (House et al., 2004; MacKenzie, 1969; Misumi, 1985; Mumford et al., 2000; Olmstead et al., 1976; Roby, 1961; Whitehead, 2009). Monitoring the external environment for threats as well as opportunities has been identified as one of the primary ways in which effective leaders optimize performance (Yukl et al., 2002).

When monitoring the environment, problem solving has been one of the primary mechanisms leaders have used to optimize processes and procedures (Farr, 1982; Leavitt, 1986; Morse & Wagner, 1978; Mumford et al., 2000; Olmstead et al., 1973; Shultz, 1961; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl, 1998; Yukl et al., 1990; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979). Depending on the nature of the external environment, effective leaders have been shown to maximize their problem solving capacity by being adaptable (Cribbin, 1981; Heifetz, 1994; Lord & Maher, 1993; Luthans & Avolio, 2003; Metcalfe, 1984; Olmstead et al., 1978; Paige, 1977), while always remaining grounded through their representation (Gross, 1961; Hemphill, 1950; Kraut et al., 1989; Krech & Crutchfield, 1948; Page, 1985; Sayles, 1981; Stogdill & Shartle, 1955; Stogdill et al., 1962; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979) and stewardship of the organization (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006; Greenleaf, 1970; Sendjaya et al., 2008; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011).

From a feedback perspective, effective leaders have been shown to seek feedback (Jacobs, 1983), provide feedback (Bass, 1981; Wilson et al., 1990) and design feedback systems (Oldham, 1976) in an effort to manage performance (Kraut et al., 1989). One of the primary outcomes associated with the feedback process has been defense of institutional integrity (Selznick, 1957) and an ability to give and receive reputation input (Bell et al., 1961; Hemphill, 1959).

One of the primary themes from the literature has been that effective leaders also take steps necessary to control processes. For example, leaders have been shown to propose the appropriate procedures for performing a task (Metcalfe, 1984), audit the implementation of the procedure (Javidan & Dastmalchian, 1993), maintain standards of performance (Berkowitz, 1953), enforce rules and procedures (Hemphill et al., 1951; Miller, 1973), and ultimately take corrective action (MacKenzie, 1969). Corrective action has been shown to sometimes include discipline (Luthans & Lockwood, 1984; Oldham, 1976; Winter, 1978), including active monitoring for performance issues (Bass & Avolio, 1990) or passively waiting for issues to arise (Bass & Avolio, 1990).

Conceptual Organizational Leadership Model

The most effective leaders have a sense of obligation (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) or service (Craig & Gustafson, 1998; Javidan & Dastmalchian, 1993; Tornow & Pinto, 1976; Wong & Davey, 2007; Van Wart, 2003; Velasquez, 1992) toward their organization. When effective leaders feel accountable to the organization, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that are beneficial to the organization (Collins, 2001; Van Dierendonck & Nuijten, 2011). Behaviors of organizational leaders are expected to adhere to a somewhat consistent pattern. Based on the review of the existing literature, a conceptual model of the organizational leadership framework is proposed in this article; the model synthesizes the previous taxonomic recommendations within the literature (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002).

According to the literature, an expected first step within the organizational leadership process would be to acquire information (Fleishmen et al., 1991). Specifically, effective leaders have been shown to use their awareness of a situation (Berkowitz, 1953) to identify the need for additional information (Metcalfe, 1984) and to consequently take action (Winter, 1978). In addition to being competent (Mumford et al., 2000) and having the requisite wisdom (Barbuto & Wheeler, 2006) and expertise (Wilson et al., 1990) to be successful in their position, effective leaders have been shown to acknowledge their responsibility to serve (Craig & Gustafson, 1998; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) and to seek information accordingly. Their ability to network (Senge, 1995; Yukl, 1998) and interact with others (Luthans & Lockwood, 1984) has been shown to be an effective channel through which to acquire information.

After acquiring information, effective leaders have been shown to clarify, organize, and evaluate information (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). Specifically, a leader’s technical or content competence (Heifetz, 1994; Katz, 1955) has been shown to be related to their ability to analyze (Lord & Maher, 1993), clarify (Wilson et al., 1990; Yukl, 1998), and process information (Hitt et al., 1983) based on internal ethics, morals, and values (i.e. Heifetz, 1994; Walumbwa et al., 2008).

Once the prerequisite information has been acquired and evaluated, effective leaders identify needs and requirements (Fleishman et al., 1991). Based on their leadership position (Fielder, 1967; Terry, 1993), effective leaders have been shown to make decisions (Luthans & Lockwood, 1984) and establish standards related to requirements (Nealy & Fiedler, 1968). Formal positional power (Fiedler, 1967) in the form of management (Clement & Ayers, 1976; Winter, 1978) has not been identified as a requirement for effective organizational leadership in this regard; effective leaders have been shown to use power in upward, lateral, and downward directions (Fleishman et al., 1991; Terry, 1993).

Planning and coordinating activities has tended to follow the identification of needs and requirements (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). The literature indicates effective leaders tend to plan (e.g. Yukl, 1998), organize (e.g. Hitt et al., 1983), and coordinate (e.g. Luthans & Lockwood, 1984) extensively. Additionally, the ability to plan and change through assertiveness (House et al., 2004), facilitation (Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986), influence (Bolman & Deal, 1991), and direction (Hersey & Blanchard, 1969) has been identified. As a consequence of planning and coordinating, leaders have been found to establish trust (Bass & Farrow; 1977; Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995) and loyalty (Velasquez, 1992) within the organization. However, it is important to note that when leaders have taken on too much responsibility for the organization, there have been instances where work avoidance (Heifetz, 1994) and abdicating of responsibility to the leader (Miller, 1973) have resulted.

As a set of central tasks within the organizational leadership model, planning and coordinating have been conceptualized to link to multiple subsequent activities, specifically, risk taking, communicating information, and material and personnel related tasks. Planning has been associated with risk taking under conditions where there has been an innovative component to the plan or coordinated action (Bass & Avolio, 1990; Kouzes & Posner, 2002; Podsakoff et al., 1990).

Based on their willingness to take risks within the scope of their plans, the literature has indicated that organizational leaders must also be able to articulate a compelling vision that is sufficiently inspirational (Yukl et al., 2002). Specifically, effective leaders have been shown to establish goals (e.g. House, 1977), vision (e.g. Greenleaf, 1970), and purpose (e.g. George, 2003) to motivate (e.g. Bass & Avolio, 1990) and inspire (e.g. Kouzes & Posner, 2002) others.

A second primary node of activity has been identified as a leader’s ability to communicate information (Fleishman et al., 1991) such as established goals. The ability to communicate information in the form of plans (Jacobs, 1983) or a compelling vision (e.g. House, 1977) has been established as a set of critical activities. Specifically, communication is related to a leader’s ability to disseminate information (Israel et al., 1998), share information (e.g. Yukl, 1998), collaborate (Larson & LaFasto, 1989), and implement plans (Farr, 1982).

Once plans have been established and communicated, the literature indicates that effective leaders go about obtaining material and personnel resources (Fleishman et al., 1991). Specifically, leaders have been shown to identify appropriate personnel (e.g. Bolman & Deal, 1991) and empower them accordingly (e.g. Hersey & Blanchard, 1969). In coordination with the personnel related tasks, leaders have also been shown to maintain a focus on the structural aspects of accomplishing the task (e.g. Blake & Mouton, 1964; Katz & Kahn, 1977).

After the necessary personnel and material resources have been obtained, effective leaders have ensured that those resources are appropriately utilized and monitored (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). Through supervision (e.g. Clement & Ayres, 1976) and administration (Luthans & Lockwood, 1984), leaders have monitored (e.g. Yukl, 1998), evaluated (e.g. Bass, 1981), and controlled (e.g. Wilson et al., 1990) the activities necessary to accomplish the task. According to the literature, leaders have also emphasized performance (Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986) and allocated rewards as a means to encourage utilization of resources (e.g. Bass & Avolio, 1990).

Maintaining material resources has also been shown to be a concern of organizational leaders (Fleishman et al., 1991). For example, maintaining equipment (Dowell & Wexley, 1978) and cost controls (Nealy & Fiedler, 1968) have been associated with leadership activities.

A final set of activities that has been found to be associated with organizational leadership has been external monitoring, feedback, and control (Fleishman et al., 1991; Yukl et al., 2002). Effective leaders have been shown to monitor the external environment based on a combination of problem solving (e.g. Mumford et al., 2000), adaptability (e.g. Heifetz, 1994) and performance orientation (e.g. House et al., 2004). In addition, literature indicates that leaders seek feedback (e.g. Bass, 1981) in an attempt to best represent the organization (e.g. Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986). However, leaders have also been known to extend feedback to a critical level, which may be seen as non-productive (Metcalfe, 1984; Van Fleet & Yukl, 1986; Yukl & Nemeroff, 1979). Additionally, leaders have been found to exercise appropriate controls through procedure enforcement (e.g. Javidan & Dastmalchian, 1993) and discipline (e.g. Bass & Avolio, 1990). A criticism within the literature has been that when leaders exert too much control, they can be seen as bureaucratic or inflexible (Birnbaum, 1988; Gupta & Govindarajan, 1984; Metcalfe, 1984; Sayles, 1981; Shrivastava & Nachman, 1989; Stogdill et al., 1965; Reddin, 1977; Wells, 1997).

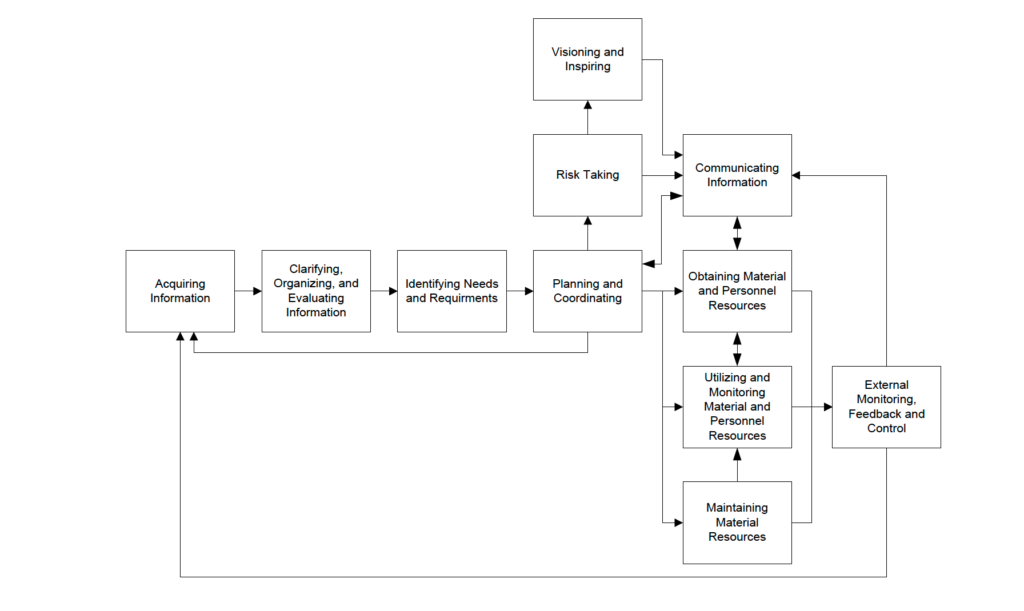

As noted in Figure 1, the aforementioned aspects of the organizational leadership conceptual model are connected, sometimes serving as prerequisites for one another. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, decisions made within organizations affect the people, resources, and direction of that organization. Therefore, the single and double arrows indicate the iterative, rather than linear, process of organizational leadership action and influence. Though much is done to create and control the internal environment of the organization, the inevitable influence of external environmental factors is visually indicated by the need for external monitoring to affect multiple areas of organizational leadership. As indicated, visioning and inspiring is powerful and necessary. Though multiple organizational leadership behaviors funnel into visioning, its significance can affect the adoption of those behaviors. Lastly, as mentioned previously, formal positional leadership is not always needed to fulfill some of the organizational leadership behaviors proposed in the model.

Conclusion

Though the importance of organizational leadership is well-known throughout popular press and academic literature, there remains a need to develop models and improve theories that assist current leaders in addressing the myriad of challenges and opportunities they face in the midst of social, economic, technological, and organizational change (Pelster, 2013). The purpose of this article sought to propose a foundational, theory-based organizational leadership model, one distinct from management roles within organizations (Lunenburg, 2011). Existing organizational leadership literature was synthesized to create a conceptual framework of leadership behavior in organizations.

As a next step, agricultural educators are encouraged to adopt, or adjust, the proposed model when facilitating learning about organizational leadership topics. Some of the 11 synthesized areas proposed in the model are missing from leadership curriculum, while others are taught in silos rather than in a holistic way that helps students see how the topics fit into the larger picture of organizational life. In addition to adult learners being able to seamlessly apply the model to their organizational settings and experiences, the framework can also be used to help undergraduate students better understand the leadership roles of their student-led agricultural organizations. The framework can also be used in graduate studies or non-higher education professional settings to create case studies that need a framework to determine if an organizational leader is adaptive to the complex changes internally and externally affecting their organization. Attaching real-time decisions to the aspects of the model can create meaningful learning opportunities for organizational members interested in applying theory to praxis.

Future research is recommended to determine if any factors relating to societal changes and diverse employee dynamics (i.e. women’s leadership, generational differences, global agriculture, etc.) are already sufficiently addressed by the model’s existing factors or need to be addressed more specifically. For a specific example, unavoidable societal change over the past several years has related to the digital interface. Digital and technology intelligence as a necessary skill is becoming more of a requirement than a preference for organizations that seek to compete in a global and changing environment. As digitization affects organizations’ structures, security, operating models, and communication and recruitment strategies, dedicated leaders equipped with the right skills are needed (Link, 2018). However, what organizational leadership looks like in this area continues to evolve (Link, 2018); the proposed model can be effective in helping with this evolution and can be adapted to the need of digital intelligence.

Other topics that influence organizations such as internal politics, organizational culture, mergers, and industry idiosyncrasies should also be looked at as factors to integrate into the organizational leadership characteristics that have been discussed. These types of topics make each organizational context different, therefore elevating contextual factors as important mediators to review when furthering this research. The initial conceptual model presented in this article should set a foundation upon which emergent models and theories can be built, equipping agricultural leaders with appropriate and necessary tools to be knowledgeable, intentional, and adaptive.

References

Abbatiello, A., Knight, M., Philpot, S., & Roy, I. (2017). Leadership disrupted: Pushing the boundaries, 2017 global human capital trends. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/human-capital-trends/2017/developing-digital-leaders.html?id=gx:2el:3dc:dup3822:awa:cons:hct17

Barbuto Jr., J. E., & Wheeler, D. W. (2006). Scale development and construct clarification of servant leadership. Group and Organizational Management, 31(3), 300-326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601106287091

Barnard, C. I. (1946). The nature of leadership. In S. D. Hosclett (Ed.), Human factors in management. New York: McGraw Hill.

Barrick, M. R., Day, D. V., Lord, R. G., & Alexander, R. A. (1991). Assessing the utility of executive leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(1), 9-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(91)90004-L

Bass, B. M. (1981). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership. New York: The Free press.

Bass, B. M. (2008). The bass handbook of leadership. New York, NY: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). Transformational leadership development: Manual for the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Bass, B. M., & Farrow, D. L. (1977). Quantitative analyses of biographies of political figures. Journal of Psychology, 97, 281-296. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1977.9923975

Beckhard, R. (1995). On future leaders. In F. Hesselbein, M. Goldsmith & R. Beckhard (Eds.), The leader of the future. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bell, W., Hill, R. J., & Wright, C. R. (1961). Public leadership: A critical review with special reference to adult education. San Francisco: Chandler.

Bennett, E. B. (1971). Discussion, decisions, commitment, and consensus in “group decision”. Human Relations, 8, 251-273. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675500800302

Bennis, W. G. (1989). Managing the dream: Leadership in the 21st century. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 2, 6-10. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534818910134040

Berkowitz, L. D. (1953). An exploratory study of the roles of aircraft commanders. Brooks Air Force Base, TX: USAF Human Resources Research Center Bulletin.

Birnbaum, R. (1988). Responsibility without authority: The impossible job of the college president. New York: National Center for Postsecondary Governance and Finance, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1964). The managerial grid. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (1991). Reframing organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Bonjean, C. M., & Olson, D. M. (1964). Community Leadership: directions of research. Administrative Science Quarterly. 9(3). 278-300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391442

Bowers, D. B., & Seashore, S. E. (1972). Predicting organizational group effectiveness with a four factor theory of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly, 11, 238-263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391247

Bradford, D. L., & Cohen, A. R. (1984). The postheroic leader. Training & Development Journal, 38(1), 40-49.

Canwell, A., Dongrie, V., Neveras, N., & Stockton, H. (2014). Leaders at all levels: Close the gap between hype and readiness. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/focus/human-capital-trends/2014/hc-trends-2014-leaders-at-all-levels.html

Clement, S. D., & Ayres, D. B. (1976). The matrix of organizational leadership dimensions. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Administration Center.

Coffin, T. E. (1944). A three-component theory of leadership. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 39(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054371

Collins, J. C. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap–and others don’t. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. (1998). Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Craig, S. B., & Gustafson, S. B. (1998). Perceived leader integrity scale: An instrument for assessing employee perceptions of leader integrity. Leadership Quarterly, 9, 127-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90001-7

Davis, F. J. (1951). Conceptions of official leader roles in the air force. Social Forces, 253-258. https://doi.org/10.2307/2573243

Day, D. V., & Lord, R. G. (1988). Executive leadership and organizational performance: Suggestions for a new theory and methodology. Journal of Management, 14(3), 453-464. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638801400308

Deloitte. (n.d.). Global human capital trends library. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/human-capital/articles/gx-human-capital-trends-library-collection.html#

Dennis, R. S., & Bocarnea, M. (2005). Development of the servant leadership assessment instrument. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26, 600-615. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730510633692

Dowell, B. E., & Wexley, K. N. (1978). Development of a work behavior taxonomy for first line supervisors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 563-572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.5.563

Elliott, M. P., Harden, J. T., Giesler, R. W., Scott, A. C., & Euske, N. (1979). The process and procedures used for job preparation: Field artillery and infantry, officers and NCOs. Carmel, CA: McFan Frey & Associates.

Farr, J. L. (1982). A five-factor system of leadership. Greensboro, NC: Farr Associates.

Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fine, S. E. (1977). Job analysis for heavy equipment operators. (). Washington, D.C.: International Union of Operating Engineers.

Fleishman, E. A. (1953). The description of supervisory behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056314

Fleishman, E. A., Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Levin, K. Y., Korotkin, A. L., & Hein, M. B. (1991). Taxonomic efforts in the description of leader behavior: A synthesis and functional interpretation. The Leadership Quarterly, 2(4), 245-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(91)90016-U

George, B. (2003). Authentic leadership: Rediscovering the secrets to creating lasting value. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gilbert, A. C. (1975). Dimensions of certain army officer positions derived by factor analysis. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute.

Graen, G., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

Greenleaf, R. K. (1970). The servant as leader. Indianapolis, IN: Robert K. Greenleaf Center.

Gross, E. (1961). Dimensions of leadership. Personnel Journal, 40, 213-218.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (1984). Build, hold, harvest: Converting strategic intentions into reality. The Journal of Business Strategy, 4(3), 34-47.

Haiman, F. S. (1951). Group leadership and democratic action. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Halpin, A. W., & Winer, J. B. (1957). A factorial study of the leader behavior descriptions. In R. M.Stogdill, & A. E. Coons (Eds.), Leader behavior: Its description andmeasurement (pp. 39-51). Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, Bureau of BusinessResearch.

Har-Evan, S. (1992). Four models of leadership persuade you. Seminar on Leadership, Tel Aviv: Open University.

Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Helme, W. H. (1971). Dimensions of leadership in a simulated combat situation. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.21236/AD0734325

Helme, W. H. (1974). Leadership research findings applied to the officer personnel management system. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute.

Hemphill, J. K. (1950). Leader behavior description. Columbus, OH: Ohio State Personnel Research Board.

Hemphill, J. K., Siegel, A., & Westie, C. W. (1951). An exploratory study of relations between perceptions of leader behavior, characteristics, and expectations concerning the behavior of ideal leaders. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, Personnel Research Board.

Hemphill, J. K. (1959). Job descriptions for executives. Harvard Business Review, 37. 55-67. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.1959.tb00090.x

Hersey, P., & Blanchard, K. H. (1969). Management of organizational behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hitt, M., Middlemist, R., & Mathis, R. (1983). Management: Concepts and effective practice. New York: West Publishing Co.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hook, S. (1943). The hero in history. New York: John Day. https://doi.org/10.2307/2262638

House, R. J. (1977). A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. In J. G. Hunt, & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership: The cutting edge. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., & Mitchell, T. R. (1974). Path-goal theory of leadership. Journal of Contemporary Business, 3, 81-97.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173-202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173

Jacobs, O. (1983). Leadership requirements for the air land battle. Paper Presented at the Leadership on the Future Battle Field Symposium, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX.

Javidan, M., & Dastmalchian, A. (1993). Assessing senior executives: The impact of context on their roles. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 29, 289-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886393293004

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. L. (1977). The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley.

Katz, R. L. (1955). Skills of an effective administrator. Harvard Business Review, 33(1), 33-42.

Kessing, F. M., & Kessing, M. M. (1956). Elite communication in Samoa: A study of leadership. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kirk, P., & Shutte, A. M. (2004). Community leadership development. Community Development Journal, 39(3), 234-251. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsh019

Komaki, J. L., Zlotnick, S., & Jensen, M. (1986). Development of an operant-based taxonomy and observational index of supervisory behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 260-269.https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.71.2.260

Koontz, H., O’Donnell, C., & Weihrich, H. (1958). Management. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (2002). The leadership challenge (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kraut, A. I., Pedigo, P. R., McKenna, D. D., & Dunnette, M. D. (1989). The role of the manager: What’s really important in different management jobs. Academy of Management Executive, 3, 286-293. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1989.4277405

Krech, D., & Crutchfield, R. S. (1948). Theory and problems of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill. https://doi.org/10.1037/10024-000

Larson, C. E., & LaFasto, F. M. J. (1989). Teamwork: What must go right; what can go wrong. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Laub, J. A. (1999). Assessing the servant organization: Development of the servant organizational leadership assessment (SOLA) instrument (Ed.D.). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text. (304517144). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304517144?accountid=10920

Leavitt, H. J. (1986). Corporate pathfinders. New York: Dow Jones-Irwin and Penguin Books.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadership Quarterly, 19, 161-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

Link, J. (2018). Why organizations need digital leaders with these five key strengths. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbeshumanresourcescouncil/2018/10/04/why-organizations-need-digital-leaders-with-these-five-key-strengths/#23c3aa7a7aee

Lord, R. G., & Maher, K. J. (1991). Leadership and information processing: Linking perceptions and performance. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Lord, R. G., & Maher, K. J. (1993). Leadership and information processing: Linking perceptions and performance. New York: Routledge.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Leadership versus management: A key distinction—at least in theory. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 14(1), 1-4.

Luthans, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Authentic leadership development. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 241-258). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Luthans, F., & Lockwood, D. L. (1984). Toward an observation system for measuring leader behavior in natural settings. In J. G. Hunt, D. Hosking, C. A. Schriesheim & R. Stewart (Eds.), Leaders and managers: International perspectives on managerial behavior and leadership (pp. 117-141). New York: Pergamon Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-030943-9.50020-6

Mackenzie, R. A. (1969). The management process in 3-D. Harvard Business Review, 47, 80-87.

Mahoney, T. A., Jerdee, T. H., & Carroll, S. I. (1965). The job of management. Industrial Relations, 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.1965.tb00922.x

Manz, C. C., & Sims Jr., H. P. (1993). Superleadership: Beyond the myth of heroic leadership. In D.Bohl (Ed.), New dimensions in leadership. New York: American Management Association.

McGrath, J. E. (1964). Leadership behavior: Some requirements for leadership training. Office of Career Development, U.S. Civil Service Commission.

Metcalfe, B. A. (1984). Microskills of leadership: A detailed analysis of the behaviors of managers in the appraisal interview. In J. G. Junt, D. M. Hosking, C. A. Schriesheim & R.Stewart (Eds.), Leaders and managers: International perspectives on managerialbehavior and leadership. New York: Permagon Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-030943-9.50023-1

Miller, J. A. (1973). The hierarchical structure of leadership behaviors. (Technical Report v64). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The nature of managerial work. New York: Harper & Row.

Misumi, J. (1985). The behavioral science of leadership. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Morse, J. J., & Wagner, F. R. (1978). Measuring the process of managerial effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 23-35. https://doi.org/10.5465/255659

Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 11-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(99)00041-7

Oldham, G. R. (1976). The motivational strategies used by supervisors: Relationships to effectiveness indicators. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15, 66-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90029-5

Olmstead, J. A., Baranick, M. J., & Elder, L. (1978). Research on training for brigade command groups: Factors contributing to unit combat readiness. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization.

Olmstead, J. A., Cleary, F. D., Lackey, L. L., & Salter, J. A. (1976). Functions of battalion command groups. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization.

Olmstead, J. A., Cleary, F. D., & Salter, J. A. (1973). Leadership activities of company command officers. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization.

Olmstead, J. S., Lackey, L. L., & Christenson, H. E. (1975). Leadership actions as evaluated by experienced company grade officers. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization.

Page, R. (1985). The position description questionnaire. Minneapolis, MN: Control Data Business Advisors.

Paige, G. D. (1977). The scientific study of political leadership. New York: Free Press.

Pelster, B. (2013). Leadership next: Debunking the superhero myth. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/human-capital/articles/leadership-next.html

Pigg, K. E. (1999). Community leadership and community theory: A practical synthesis. Journal of Community Development Society, 30(2), 196-212. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575339909489721

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

Prien, E. P. (1963). Development of a supervisor position description questionnaire. Journal of Applied Psychology, 47(1), 10-14. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041308

Quinn, R. E., Dixit, N., & Faerman, S. R. (1987). Perceived performance: Some archetypes of managerial effectiveness and ineffectiveness. Albany, NY: State University of New York at Albany, Nelson A. Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy, Institute for Government and Policy Studies.

Reaser, J. M., Vaughan, M. R., & Kriner, R. E. (1974). Military leadership in the seventies: A closer look at the dimensions of leadership behavior. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization. https://doi.org/10.21236/ADA083599

Reddin, W. J. (1977). An integration of leader-behavior typologies. Group & Organization Studies, 25(3), 282-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200303

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. (2009). Organizational behavior. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Roberts, T. G., Harder, A., & Brashears, M. T. (Eds). (2016). American Association for Agricultural Education national research agenda: 2016-2020. Retrieved from http://aaaeonline.org/resources/Documents/AAAE_National_Research_Agenda_2016-2020.pdf

Roby, T. B. (1961). The executive function in small groups. In L. Petrullo, & B. Bass (Eds.), Leadership and interpersonal behavior. New York: Holt, Reinhart, & Winston.

Rothschild, W. E. (1993). Risktaker, caretaker, surgeon, undertaker: The four faces of strategic leadership. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Sayles, L. R. (1981). Leadership: What effective managers usually do and how they do it. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schein, E. (1995). Organizational and managerial culture as a facilitator or inhibitor of organizational transformation. (No. Working Paper 3831). Cambridge, MA: MIT Sloan School of Management.

Schermerhorn, J. R., Hunt, J. G., & Osborn, R. N. (1982). Managing organizational behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Selznick, P. (1957). Leadership in administration: A sociological interpretation. Evanston, IL: Row & Peterson.

Sendjaya, S., Sarros, J. C., & Santora, J. C. (2008). Defining and measuring servant leadership behaviour in organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), 402-424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00761.x

Senge, P. M. (1995). Reflection of leadership: How Robert K. Greenleaf’s theory of servant-leadership influenced today’s top management thinkers. Robert Greenleaf’s legacy: A new foundation for twenty-first century institutions (pp. 217-240). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Shrivastava, P., & Nachman, S. A. (1989). Strategic leadership patterns. Strategic Management Journal, 51-66. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100706

Showel, M., & Peterson, C. W. (1958). A critical incident study of infantry, airborne, and armored junior noncommissioned officers. Alexandria, VA: Human Resources Research Organization.

Shultz, W. C. (1961). The ego theory and the leader as completer. In L. Petrullo, & B. Bass (Eds.), Leadership and interpersonal behavior. New York: Holt, Reinhart, & Winston.

Society for Human Resource Management. (2015). SHRM research overview: Leadership development. Retrieved from https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/special-reports-and-expert-views/Documents/17-0396%20Research%20Overview%20Leadership%20Development%20FNL.pdf

Stogdill, R. M., Goode, O. S., & Day, D. R. (1962). New leader behavior description subscales. Journal of Psychology, 54, 259-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1962.9713117

Stogdill, R. M., Goode, O. S., & Day, D. R. (1965). The leader behavior of university presidents. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University, Bureau of Business Research.

Stogdill, R. M., & Shartle, C. L. (1955). Methods in the study of administrative leadership. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University.

Stogdill, R. M., Wherry, R. J., & Jaynes, W. E. (1953). Patterns of leader behavior: A factorial study of navy officer performance. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University.

Suttel, B. J., & Spector, O. (1955). Research on the specific leader behavior patterns most effective in influencing group performance. Washington, D. C.: American Institutes for Research.

Tannenbaum, R., & Schmidt, W. H. (1958). How to choose a leadership pattern. Harvard Business Review, 36(2), 95-101.

Terry, R. W. (1993). Authentic leadership: Courage in action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Törnblom, O. (2018). Managing complexity in organizations: Analyzing and discussing a managerial perspective on the nature of organizational leadership. Behavioral Development, 23(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/bdb0000068

Tornow, W. W., & Pinto, P. R. (1976). The development of a managerial job taxonomy: A system for describing, classifying and evaluating executive positions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 410-418. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.61.4.410

Van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 249-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

Van Fleet, D. D., & Yukl, G. A. (1986). Military leadership: An organizational behavior perspective. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Van Wart, M. (2003). Public-sector leadership theory: An assessment. Public Administration Review, 63(2), 214-228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00281

Velasquez, M. G. (1992). Business ethics: Concepts and cases (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34(1), 89-126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307308913

Wells, S. (1997). From sage to artisan: The nine roles of the value-driven leader. Palo Alto: Davies-Black Publishing.

Whitehead, G. (2009). Adolescent leadership development building a case for an authenticity framework. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 37(6), 847-872. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143209345441

Williams, R. E. (1956). A description of some executive abilities by means of the critical incident technique. (Unpublished Doctoral dissertation.). Columbia University, New York.

Wilson, C. L., O’Hare, D., & Shipper, F. (1990). Task cycle theory: The processes of influence. In K. E. Clark, & M. B. Clark (Eds.), Measures of leadership (pp. 185-204). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America.

Winter, D. G. (1978). Navy leadership and management competencies: Convergence among tests, interviews, and performance ratings. Boston, MA: McBer & Company.

Wofford, J. C. (1967). Behavior styles and performance effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 20, 461-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1967.tb02445.x

Wong, P. T. P., & Davey, D. (2007). Best practices in servant leadership. Paper Presented at the Servant Leadership Research Roundtable, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

Yukl, G. (1998). Leadership in organizations (4th ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Yukl, G., Gordon, A., & Taber, T. (2002). A hierarchical taxonomy of leadership behavior: Integrating a half century of behavior research. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(1), 15-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900102

Yukl, G. A., & Nemeroff, W. (1979). Identification and measurement of specific categories of leadership behavior: A progress report. In J. G. Hunt, & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Crosscurrents in leadership (pp. 164-200). Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Yukl, G., Wall, S., & Lepsinger, R. (1990). Preliminary report on validation of the managerial practices survey. In K. E. Clark, & M. B. Clark (Eds.), Measures of leadership (pp. 223-238). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America.

Zaleznik, A. (1977). Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, 55, 67-78.