Christopher J. Eck, Oklahoma State University, chris.eck@okstate.edu

Abstract

Teaching effectiveness is an elusive, difficult to gauge concept, especially in career and technical education. This exploratory study was undergirded by the human capital theory and the effective teaching model for SBAE teachers. The purpose of this study was to identify the overall effectiveness of SBAE teachers aiming to improve their human capital by attending professional development at the 2020 NAAE conference. Composite effectiveness scores on the effective teaching instrument for school-based agricultural education teachers (ETI-SBAE) ranged from 59 to 98, out of 104, with a mean score of 81.54 overall. Work-life balance was found to be the component of greatest concern, followed by SAE supervision. Female SBAE teachers were found to be more effective than their male counterparts in this self-reported study. Determining effectiveness using the ETI-SBAE allows teachers to reflect upon their current human capital, ultimately guiding professional development opportunities to improve their effectiveness. SBAE stakeholders responsible for developing professional development workshops should consider the needs of their target audience and be purposeful in the offerings provided, as needs of SBAE teachers vary across a wide spectrum of personal and professional characteristics.

Introduction/Theoretical Framework

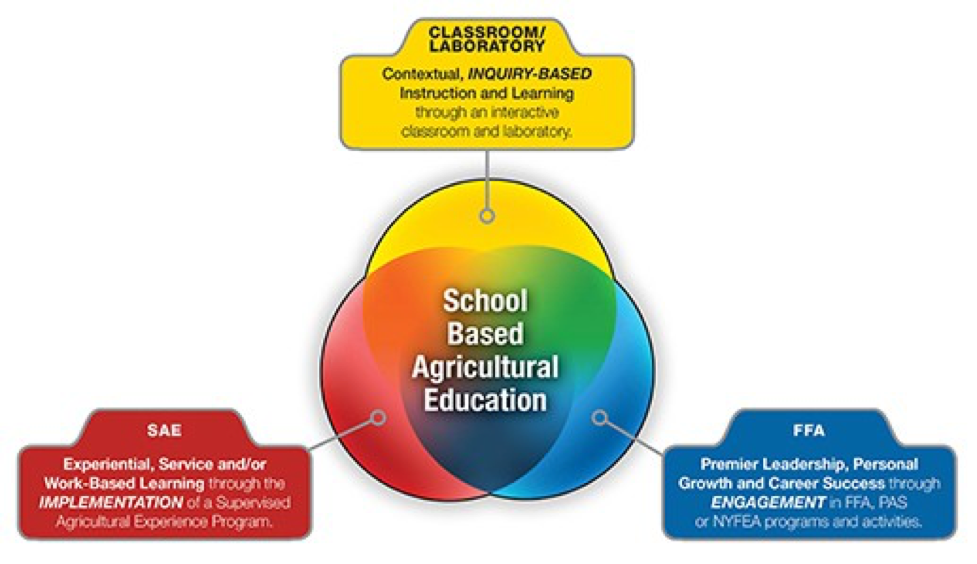

Teaching effectiveness has often been considered an elusive concept (Stronge et al., 2011), as it has multiple definitions and evaluation metrics (Farrell, 2015), although, studies (Kane & Staiger, 2008; Stronge et al., 2011) have found a link between teaching effectiveness and students’ success. As with career and technical education (CTE) at large, considering the effectiveness of school-based agricultural education (SBAE) teachers becomes an even more daunting task (Eck et al., 2019). Evaluating SBAE teachers differs from those within core subject areas, as SBAE teachers have unique workloads and expectations (Roberts & Dyer, 2004). The expectations of an SBAE teacher are often designed based on the National FFA Organization’s (2015) three-component model of agricultural education, (i.e., classroom and laboratory instruction, FFA advisement, and supervised agricultural experience (SAE) supervision). Figure 1 outlines the three-component model along with integral details.

Figure 1

The Three-Component Model of Agricultural Education (National FFA Organization, 2015)

The components outside of classroom and laboratory instruction (i.e., SAE and FFA) are considered intracurricular, as they are a comprehensive part of a complete SBAE program (National FFA Organization, 2015). Although these components are intracurricular, the time SBAE teachers must commit to overseeing these tasks is time consuming and often daunting for newer teachers (Torres et al., 2008). Many of these additional tasks go unnoticed by supervisors and administrators even though teachers often struggle preparing for class (Boone & Boone, 2007) and balancing the additional workload (Boone & Boone 2009). This workload and the increased community expectation placed on SBAE teachers often leads to the concern of work-life balance (Clemons et al., 2021; Edwards & Briers, 1999; Murray et al., 2011; Traini et al., 2020; Sorensen et al., 2016). Additionally, work-life balance has been identified as an integral component of an effective SBAE teacher (Eck et al., 2020). But finding this balance can be an overwhelming task considering the extra duties and responsibilities placed on SBAE teachers (Terry & Briers, 2010). Regardless of the subject area many can agree that “teachers make a difference” (Wright et al., 1997, p. 57), which leads to the need for support structures for teachers.

One critical way that teachers are supported is through professional development opportunities (Desimone, 2011). Unfortunately, professional development is often broad and not developed based on teacher’s needs, leading to little or no benefit to the teachers participating (National Research Council, 2000). Research within SBAE often focuses on the needs of teachers but professional development is rarely designed to meet those needs (Easterly & Myers, 2019). Therefore, it is essential that teachers’ needs are not only evaluated but the opportunity to address those needs through purposeful professional development is explored.

This study aimed to address the overarching concern related to professional development and the alignment of SBAE teachers’ needs by evaluating their teaching-specific human capital during a professional development workshop. Thus, this study was framed by the conceptual model for effective teaching in SBAE (Eck et al., 2020). The model was undergirded by the human capital theory (HCT), as HCT addresses an individual’s experiences, education, skills, and training (Becker, 1964; Little, 2003; Schultz, 1971; Smith, 2010; Smylie, 1996) specific to their career (Heckman, 2000). As the educational landscape continues to change, it becomes increasingly important to assess and update career specific human capital (Spenner, 1985).

To help address the specific concerns related to SBAE teaching, Eck et al. (2020) developed and validated the effective teaching instrument for school-based agricultural education teachers (ETI-SBAE) in response to the growing interest in developing comprehensive evaluation systems for education (Darling-Hammond, 2010), specifically those unique to SBAE (Eck et al., 2019; Roberts & Dyer, 2004). To further support the professional development of SBAE teachers, a conceptual model was established to connect the primary components of SBAE teacher human capital development and effective teaching in a complete SBAE program. Figure 2 depicts the effective teaching model for SBAE teachers (Eck et al., 2020), which supports the ETI-SBAE by grounding the instrument in the human capital theory.

Figure 2

The Effective Teaching Model for SBAE Teachers

Since human capital focuses on the education, skills, experiences, and training (Little, 2003; Schultz, 1971; Smith, 2010; Smylie, 1996) specifically related to one’s career (Becker, 1964), the model is encompassed by the development of human capital. The effective teaching model (see Figure 2) aligns the six components of effective SBAE teachers from the ETI-SBAE along with personal, professional, and environmental factors, all of which are necessary elements of human capital for SBAE teachers (Eck et al., 2020). Although the ETI-SBAE exists, little research has been conducted related to the evaluation and growth of SBAE teachers seeking to increase their human capital through professional development opportunities. The ETI-SBAE and the accompanying conceptual model were established to help in-service SBAE teachers conceptualize their personal strengths and weaknesses as they relate to effective teaching in a complete SBAE program (Eck et al., 2020). Therefore, this study aimed to determine the self-perceived effectiveness of SBAE teachers related to the effective teaching model, who were participating in the 2020 National Association of Agricultural Educators (NAAE) annual conference who were taking part in professional development opportunities. The workshop provided career specific professional development for SBAE teacher participants, which served as a training (Schultz, 1971) aimed at increasing career specific human capital (Becker, 1964).

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to identify the overall effectiveness of SBAE teachers aiming to improve their human capital by attending professional development at the 2020 NAAE conference. Two research objectives guided the study: (1) Determine the self-perceived effectiveness of SBAE teachers attending professional development at the 2020 NAAE Conference; and (2) Compare the effectiveness of SBAE teachers based on personal and professional characteristics.

Methods and Procedures

This non-experimental study implemented an exploratory survey research design (Privitera, 2020) during a professional development workshop at the 2020 NAAE Virtual Conference. The population of interest included SBAE teachers nationwide, but an accessible population (Privitera, 2020) was surveyed that participated in the virtual workshop titled, Be Purposeful About Your Professional Development: How to Increase Your Teaching Effectiveness (n = 32), during the conference. During the virtual presentation, teachers were asked to complete a survey instrument to help them self-evaluate their overall effectiveness. Out of the 32 participants, 28 (87.5%) completed the instrument.

The ETI-SBAE was the instrument used during the workshop as it was deemed a valid and reliable instrument to self-assess SBAE teacher effectiveness by Eck et al. (2020), with an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 (Nunnally, 1978). The instrument included 26-items (see Table 1) spanning six components (i.e., Intracurricular Engagement, Personal Dispositions, Appreciation for Diversity and Inclusion, Pedagogical Preparedness, Work-Life Balance, and Professionalism).

Table 1

Effective Teaching Components and Item Descriptions (26 items)

| Component Title | Item | Corresponding Item Description | ||

| 1. Intracurricular Engagement | IE_1 | I instruct students through FFA. | ||

| IE_2 | I advise the FFA officers. | |||

| IE_3 | I advise the FFA chapter. | |||

| IE_4 | I facilitate record keeping for degrees and awards. | |||

| IE_5 | I am passionate about FFA. | |||

| IE_6 | I instruct students through SAEs. | |||

| IE_7 | I use the complete agricultural education 3- component model as a guide to programmatic decisions. | |||

| 2. Personal Dispositions | PD_1 | I am trustworthy. | ||

| PD_2 | I am responsible. | |||

| PD_3 | I am dependable. | |||

| PD_4 | I am honest. | |||

| PD_5 | I show integrity. | |||

| PD_6 | I am a hard worker. | |||

| 3. Appreciation for Diversity and Inclusion | AD_1 | I value students regardless of economic status. | ||

| AD_2 | I value students of all ethnic/racial groups. | |||

| AD_3 | I value students regardless of sex. | |||

| AD_4 | I care about all students. | |||

| AD_5 | I understand there is not an award for all students, but that does not mean they are not valuable. | |||

| 4. Pedagogical Preparedness | PP_1 | I demonstrate classroom management. | ||

| PP_2 | I demonstrate sound educational practices. | |||

| PP_3 | I am prepared for every class. | |||

| 5. Work-Life Balance | B_1 | I have the ability to say no. | ||

| B_2 | I lead a balanced life. | |||

| B_3 | I am never afraid to ask for help. | |||

| 6. Professionalism | P_1 | I have patience. | ||

| P_2 | I show empathy. | |||

In addition to the 26-item instrument, five questions were asked related to personal and professional characteristics (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, certification pathway, and number of years teaching SBAE).

Workshop participants rated each of the 26-items on a 4-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 4 (i.e., 1 = very weak; 2 = weak; 3 = strong; 4 = very strong) based on their personal assessment of strengths and weaknesses. A composite effectiveness score was calculated based on the recommendations of Eck et al. (2020) to assess overall teacher effectiveness based on a sum of the responses to the 26-items. The summative scores were equally weighted across the 26-items to provide optimal estimates according to McDonald (1997). The composite scores were calculated using Microsoft Excel®, with a possible range of 26 (very weak) to 104 (very strong). Composite effectiveness ranges were provided to participants during the workshop as follows: weak = 26 to 46; somewhat weak = 47 to 67; strong = 68 to 88; and very strong = 89 to 104.

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 26 and included descriptive and inferential statistics. Specifically, research objective one used descriptive statistics to report mean and standard deviation using SPSS, while also implementing Microsoft Excel to calculate composite effectiveness scores. The composite effectiveness scores were then used in research objective two as the dependent variable to compare against the five independent variables or personal and professional characteristics (i.e., gender, age, ethnicity, certification pathway, and years teaching) using a factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA), per the recommendations of Field (2009). The factorial ANOVA output from SPSS was analyzed to identify interactions and potential main effects of the data (Field, 2014). To further explain the effect, an effect size was calculated for the factorial ANOVA as partial eta squared (n2). The resulting effect size (n2 = 0.44) was considered a large effect (n2 > .25) according to Privitera (2020).

SBAE teachers participating in the NAAE workshop ranged from 24 to 53 years of age, with 78.6% being female (see Table 2). Twenty-one of the teachers (75.0%) were traditionally certified through either a bachelor’s or master’s agricultural education degree program with student teaching and ranged from first year teachers to those with 28 years of experience (see Table 2). Table 2 outlines the personal and professional characteristics of all SBAE teachers participating in the virtual workshop who completed the ETI-SBAE during the 2020 NAAE Virtual Conference.

Table 2

Personal and Professional Characteristics of Participants (n = 28)

| Characteristic | n | % | ||||

| Gender | Male | 5 | 17.9 | |||

| Female | 22 | 78.6 | ||||

| Prefer to not respond | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| Age | 21 to 29 | 4 | 14.2 | |||

| 30 to 39 | 8 | 28.6 | ||||

| 40 to 49 | 8 | 28.6 | ||||

| 50 to 59 | 3 | 10.7 | ||||

| Prefer to not respond | 5 | 17.9 | ||||

| Certification Pathway | AgEd BS | 11 | 39.3 | |||

| AgEd MS | 10 | 35.7 | ||||

| Alternatively Certified | 3 | 10.7 | ||||

| Emergency Certified | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| Not Certified | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| Prefer to not respond | 2 | 7.1 | ||||

| Ethnicity | White | 22 | 78.6 | |||

| Black or African American | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| Other | 2 | 7.1 | ||||

| Prefer to not respond | 2 | 7.1 | ||||

| Years Teaching SBAEa | 1 | 1 | 3.6 | |||

| 2 | 0 | 0.0 | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| 4 | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| 5 | 3 | 10.7 | ||||

| 6 to 10 | 6 | 21.4 | ||||

| 11 to 15 | 7 | 25.0` | ||||

| 16 to 20 | 5 | 17.9 | ||||

| 21 to 25 | 2 | 7.1 | ||||

| 26 to 30 | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

| No Response | 1 | 3.6 | ||||

Note. aYears of teaching experience was aggregated based on participant responses.

The limitations of this study should be considered, as participation was limited to those who registered for and attended the virtual workshop at the 2020 NAAE Conference titled, Be Purposeful About Your Professional Development: How to Increase Your Teaching Effectiveness. and were willing to complete the ETI-SBAE instrument during the virtual workshop. The participants were seeking professional development; therefore, the findings are limited to in-service SBAE teachers who are interested in professional development opportunities.

Findings

Findings for Research Objective One: Determine the self-perceived effectiveness of SBAE teachers attending professional development at the 2020 NAAE Conference

This study resulted in responses from 28 SBAE teachers with composite effectiveness scores ranging from 59 (weak) to 98 (very strong), out of a total of 104, with a mean of 81.54. To further understand these composite scores, Table 3 outlines the means and standard deviations of each of the 26-items on the ETI-SBAE.

Table 3

ETI-SBAE Items with Means and Standard Deviations (n = 28)

| Corresponding Item Description | M | SD | ||

| I am a hard worker. | 4.00 | .00 | ||

| I am trustworthy. | 3.96 | .19 | ||

| I am dependable. | 3.93 | .27 | ||

| I am honest. | 3.93 | .27 | ||

| I show integrity. | 3.93 | .27 | ||

| I am responsible. | 3.92 | .27 | ||

| I value students regardless of economic status. | 3.89 | .32 | ||

| I value students of all ethnic/racial groups. | 3.85 | .36 | ||

| I value students regardless of sex. | 3.85 | .36 | ||

| I care about all students. | 3.81 | .40 | ||

| I understand there is not an award for all students, but that does not mean they are not valuable. | 3.81 | .49 | ||

| I am passionate about FFA. | 3.74 | .71 | ||

| I demonstrate sound educational practices. | 3.33 | .48 | ||

| I show empathy. | 3.33 | .68 | ||

| I have patience. | 3.32 | .67 | ||

| I advise the FFA chapter. | 3.31 | .62 | ||

| I advise the FFA officers. | 3.27 | .83 | ||

| I use the complete agricultural education 3-component model as a guide to programmatic decisions. | 3.27 | .72 | ||

| I demonstrate classroom management. | 3.26 | .59 | ||

| I instruct students through FFA. | 3.23 | .71 | ||

| Corresponding Item Description | M | SD | ||

| I am prepared for every class. | 2.89 | .64 | ||

| I instruct students through SAEs. | 2.88 | .71 | ||

| I facilitate record keeping for degrees and awards. | 2.85 | .93 | ||

| I lead a balanced life. | 2.41 | .64 | ||

| I am never afraid to ask for help. | 2.37 | .88 | ||

| I have the ability to say no. | 2.33 | .68 | ||

Note. 1 = very weak, 2 = somewhat weak, 3 = somewhat strong, and 4 = very strong

As shown in Table 3, the top six items based on means (ranging from 3.92 to 4.00) were all related to personal dispositions of the SBAE teachers (i.e., I am a hard worker, I am trustworthy, I am dependable, I am honest, I show integrity, and I am responsible). The next five items all correspond with an SBAE teachers’ appreciation for diversity and inclusion (i.e., I value students regardless of economic status, I value students of all ethnic/racial groups, I value students regardless of sex, I care about all students, and I understand there is not an award for all students, but that does not mean they are not valuable), ranging in means from 3.81 to 3.85. The component related to work-life balance (i.e., I lead a balanced life, I am never afraid to ask for help, and I have the ability to say no) resulted in the lowest three mean scores, ranging from 2.33 to 2.41. Professionalism corresponds to two items; I have patience and I show empathy which resulted in mean scores of 3.32 and 3.33 respectively. Pedagogical preparedness is represented by three items (i.e., I demonstrate classroom management, I demonstrate sound educational practices, and I am prepared for every class), which ranged from a low of 2.89 to a high of 3.33. The final, and largest component is intracurricular engagement, which corresponds with seven items (i.e., I instruct students through FFA, I advise the FFA officers, I advise the FFA chapter, I facilitate record keeping for degrees and awards, I am passionate about FFA, I instruct students through SAEs, and I use the complete agricultural education 3-component model as a guide to programmatic decisions) that ranged in mean scores from 2.85 to 3.74.

Findings for Research Objective Two: Compare the Effectiveness of SBAE Teachers Based on Personal and Professional Characteristics

Respondents were asked five questions related to personal and professional characteristics, including their age, gender, ethnicity, certification pathway, and number of years teaching SBAE (see Table 2). These characteristics were then compared against the composite sum effectiveness score for each participant. The maximum possible effectiveness score was 104 points for the 26-item instrument, as identified in the first research objective respondents in this study had effectiveness scores ranging from 59 to 98 points.

Before proceeding with the statical analysis, normality and homogeneity of variance was assessed, with all responses being normally distributed and Levene’s test statistic resulting in a non-statistical significance (p > .05). With the assumptions being met, a factorial ANOVA was conducted with the composite sum effectiveness score serving as the dependent variable and the five personal and professional characteristics serving as independent variables. The SPSS output resulted in no statistically significant interactions within the factorial ANOVA. Although there were no significant interactions, main effects were analyzed, resulting in a statistically significant main effect for Gender F (17, 10) = 2.91, p < .05. Specifically, women in this study perceived themselves to be more effective (mean score = 88.50) than men (mean score = 83.20). The other for factors were not statistically significant; (1) Age F (17, 10) = 2.03, p > .05; (2) Ethnicity F (15, 10) = 1.60, p > .05; (3) Certification Pathway F (15, 10) = 0.76, p > .05; (4) Number of Years Teaching F (16, 10) = 2.35, p > .05.

Conclusions

SBAE teachers participating in the professional development session at the 2020 NAAE conference perceived themselves to be effective teachers overall according to their responses on the ETI-SBAE with a mean composite effectiveness score of 81.54. This overall composite score falls within the strong category of SBAE teaching effectiveness (i.e., strong = 68 to 88). Twenty of the items resulted in mean scores above 3.2, indicating responses of somewhat strong or very strong on the instrument. The remaining six items ranged in mean scores from a high of 2.89 (I am prepared for every class) to a low of 2.33 (I have the ability to say no), indicating somewhat weak areas for the SBAE teachers. Specifically, the component of greatest concern was work-life balance with the lowest three mean scores. Work-life balance is not a new concern, as the continual increase in SBAE teacher workload and community expectation has been an ongoing discussion within the literature (Boone & Boone, 2009; Clemons et al., 2021; Edwards & Briers, 1999; Murray et al., 2011; Sorensen et al., 2016; Traini et al., 2020), as it ultimately impacts work-life balance.

Another area of potential concern is within the intracurricular engagement component, specifically related to SAEs. Two items focus on SAEs, including I instruct students through SAEs and I facilitate record keeping for degrees and awards. These two items resulted in mean scores of 2.88 and 2.85 respectively, which are of concern, as the fall between somewhat weak (2.0) and somewhat strong (3.0), while SAE is considered an integral component of a complete SBAE program (National FFA Organization, 2015). SAE has also been discussed as additional time SBAE teachers must commit to overseeing the associated task, which is time consuming and often daunting for newer teachers (Torres et al., 2008). Boone and Boone (2007) described these related tasks as often going unnoticed by administrators and cause teachers to struggle with class preparation. Perhaps this is further confirmed within this study, as participants reported a mean score of 2.89 for the item, I am prepared for every class.

Determining the self-perceived areas of effectiveness and needs for improvement using the ETI-SBAE allows teachers to reflect upon their current human capital (Little, 2003; Schultz, 1971; Smith, 2010; Smylie, 1996), ultimately guiding professional development opportunities to help further career specific capital (Becker, 1964). Providing teachers an opportunity for self-reflection provides them the chance to seek purposeful professional development that could result in personal benefit for them professionally, offsetting the longstanding trend of little or no benefit to the teachers (National Research Council, 2000). Regardless, professional development has been identified as a critical way to support teachers (Desimone, 2011) and this research can serve as a starting point for the recommended research on engagement in professional development designed to meet SBAE teacher needs (Easterly & Myers, 2019).

Perhaps providing SBAE teachers with a valid instrument (ETI-SBAE) to evaluate their effectiveness across a complete SBAE program (i.e., classroom and laboratory instruction, FFA advisement, and SAE supervision) will encourage them to seek purposeful professional development opportunities, potentially increasing student success (Kane & Staiger, 2008; Stronge et al., 2011). Therefore, it is recommended that SBAE teachers use the ETI-SBAE to evaluate their areas of strength and weakness to identify gaps to be filled by professional development opportunities. Supervisors and administrators of SBAE teachers should also consider the ETI-SBAE to gauge the needs of their SBAE teachers. This exploratory study represented a small sample of SBAE teachers, therefore, the replication of this study using larger pools of teachers attending professional development events is warranted. Future research should evaluate the impact of purposeful professional development on teaching effectiveness using the ETI-SBAE.

Participants represented a range of personal and professional characteristics (see Table 2), allowing teaching effectiveness to be compared across those (i.e., age, gender, ethnicity, certification pathway, and number of years teaching SBAE). The only statistically significant difference was found between gender, as women perceived themselves to be more effective than men F (17, 10) = 2.91, p < .05. Although this is only a self-perceived effectiveness, there is room for growth across the SBAE teaching spectrum. This study suggests the need for professional development opportunities related to class preparation, SAE instruction, record keeping and work/life balance (i.e., leading a balanced life, asking for help, and having the ability to say no).

Recommendations

Although teaching effectiveness has been defined as a multi-dimensional (Farrell, 2015), elusive concept (Stronge et al., 2011), the effective teaching model for SBAE teachers (see Figure 2) should be used as a guide in conjunction with the ETI-SBAE to determine the specific needs of an individual teacher based on their overall effectiveness and personal, professional, and environmental factors to increase their human capital (Becker, 1964), leading to increased teaching effectiveness. SBAE teachers should consider their strengths and weaknesses related to delivering a complete program (i.e., classroom/laboratory instruction, FFA advisement, and SAE supervision) and then seek appropriate professional development to help addresses those areas of concern. Additionally, SBAE stakeholders responsible for developing professional development workshops should consider the needs of their target audience and be purposeful in the offerings provided, as needs of SBAE teachers vary across a wide spectrum of personal and professional characteristics.

Considering recommendations for future research, SBAE teacher preparation faculty should replicate this study during in-service trainings to better understand the needs of their constituents. Research should also consider how to best support the human capital development of teachers and measure teaching effectiveness in the given space. Furthermore, qualitative inquiries should be used to explore SBAE teachers’ perceptions of the effective teaching model and instrument to further develop and refine the items to meet the needs of current teachers across the country to better support self-evaluation to provide purposeful professional development opportunities focused on increasing career specific human capital.

References

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Boone, H. N., & Boone, D. A. (2007). Problems faced by high school agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(2), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2007.02036

Boone, H. N., & Boone, D. A. (2009). An assessment of problems faced by high schoolagricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2009.01021

Clemons, C., Hall, M., & Lindner, J. (2021). What is the real cost of professional success? A qualitative analysis of work and life balance in agriscience education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 62(1), 95-113. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2021.01095

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Evaluating teacher effectiveness: How teacher performance assessments can measure and improve teaching. Center for American Progress.https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education–k-12/reports/2010/10/19/8502/evaluating–teacher–effectiveness/

Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi delta kappan, 92(6), 68–71. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003172171109200616

Easterly, R. G. T., & Myers, B. E. (2019). Professional development engagement and career satisfaction of agriscience teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(2), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.02069

Eck, C. J., Robinson, J. S., Ramsey, J. W., & Cole. K. L. (2019). Identifying the characteristics of an effective agricultural education teacher: A national study. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.04001.

Eck, C. J., Robinson, J. S., Cole, K. L., Terry Jr., R., & Ramsey, J. W. (2020). Validation of the effective teaching instrument for school-based agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(4), 229–248. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.04229

Edwards, M. C., & Briers, G. E. (2001). Cooperating teachers’ perceptions of important elements of the student teaching experience: A focus group approach with quantitative follow-up. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(3), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2001.03030

Farrell, T. S. C. (2015). It’s not who you are! It’s how you teach! Critical competencies associated with effective teaching. RELC Journal, 46(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688214568096

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Sage.

Field, A. (2014). Discovering statistics using SPSS (4th ed.). Sage.

Heckman, J. L. (2000). Invest in the very young. Chicago, IL: Ounce of Prevention Fund. http://www.ounceofprevention.org/downloads/publications/Heckman.pdf

Kane, T. J., & Staiger, D. O. (2008). Estimating teacher impacts on student achievement: An experimental evaluation. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 14607.https://doi.org/10.3386/w14607

Little, J. W. (2003). Inside teacher community: Representations of classroom practice. Teachers College Record, 105(6), 913–945. https://www.tcrecord.org/content.asp?contentid=11544

McDonald, R. P. (1997). Haldane’s lungs: A case study in path analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3201_1

Murray, K., Flowers, J., Croom, B., & Wilson, B. (2011). The agricultural teacher’s struggle for balance between career and family. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1999.01038

National FFA Organization. (2015). Agricultural education. https://www.ffa.org/agricultural-education/

National Research Council. (2000). How people learn. National Academy Press.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Privitera, G. J. (2020). Research methods for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Roberts, T. G., & Dyer, J. E. (2004). Characteristics of effective agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(4), 82–95. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2004.04082

Schultz, T. W. (1971). Investment in human capital: The role of education and of research.

The Free Press.

Smith, E. (2010). Sector–specific human capital and the distribution of earnings. Journal of Human Capital, 4(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/655467

Smylie, M. A. (1996). From bureaucratic control to building human capital: The importance of teacher learning in education reform. Educational Researcher, 25(9), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X025009009

Sorensen, T. J., McKim, A. J., & Velez, J. J. (2016). A national study of work-family balance and job satisfaction among agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(4), 146-159. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.04146

Spenner, K. I., (1985). The upgrading and downgrading of occupations: Issues, evidence, and implications for education. Review of Educational Research, 55(2), 125–154. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170188

Stronge, J. H., Ward, T. J., & Grant, L. W. (2011). What makes good teachers good? A cross-case analysis of the connection between teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(4), 339–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487111404241

Terry, R., Jr., & Briers, G. E. (2010). Roles of the secondary agriculture teacher. In R. Torres, T. Kitchel, & A. Ball (Eds.), Preparing and advancing teachers in agricultural

education (pp. 86-98). Columbus: Curriculum Materials Service, The Ohio State University.

Torres, R. M., Ulmer, J. D., & Aschenbrener, M. S. (2008). Workload distribution among agriculture teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 49(2), 75–87. https://doi.org10.5032/jae.2008.02075

Traini, H. Q., Yopp, A. M., & Roberts, R. (2020). The success trap: A case study of early career agricultural education teachers’ conceptualizations of work-life balance. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(4), 175-188. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.04175

Wright, S. P., Horn, S. P., & Sanders, W. L. (1997). Teacher and classroom context effects on student achievement: Implications for teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 11(1), 57–67.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007999204543