Authors

Mark Bloss, Pawnee City High School, Nebraska, mbloss@pawneecityschool.net

Brian Johnson, Litchfield Public Schools, Nebraska, brian.johnson@litchfieldps.org

Nathan W. Conner, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, nconner2@unl.edu

Bryan Reiling, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, breiling2@unl.edu

Mark Balschweid, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, mbalschweid2@unl.edu

Abstract

This study examined the perceptions of high school guidance counselors in Nebraska in regard to the science present in high school agriscience courses. An understanding of guidance counselors’ perceptions of science incorporated into high school agriscience courses will help agriscience instructors successfully highlight the significance of science in their courses to improve perceptions of the science that is taught in agriscience courses. Interviews were conducted with 10 guidance counselors in Nebraska. The following themes emerged from the study: (a) Science Credit for Agriscience Courses, (b) Superficial Knowledge of Agriscience Courses, (c) Real World Connections, (d) Reasons for Student Placement in Agriscience Courses, (e) Lack of High School Agriscience Experience, and (f) Agricultural Connections. Findings indicated that guidance counselors see real world applications in agriscience courses, but specific connections to science principles need to be highlighted for the agriscience courses to count as science credit. Additionally, agricultural educators who depend on sustained enrollment in agriscience courses, and for agriscience students who wish to receive science credit for those courses, it is imperative that agriscience instructors inform guidance counselors of the science taught through agriscience courses.

Introduction and Review of Literature

Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) is an interdisciplinary and applied approach to integrating the four specific disciplines. STEM integrates the four disciplines into a cohesive learning paradigm based on real-world applications (Hom, 2014). There has been increased interest in STEM education over the past few decades (Harrington, 2015). Even though the United States is considered a world leader, our students’ achievement in math and science, as well as STEM degree attainment, is low (Kuenzi, 2008). The U.S. ranks in international assessments for 15-year-old students were lower than expected. The U.S. ranked 24th in math (Kuenzi, 2008). For 24 year-old’s pursuing degrees in engineering or natural science, the U.S. ranked 20th (Kuenzi, 2008). According to the PEW research center, the United States is below average in math, but above average in science when compared to the other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Kennedy, 2024).

Science literacy is important, and the need for it is continually increasing (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983; McLure & McLure, 2000; Miller, 2010). Even though science is everywhere, high school science teachers have adjusted their curriculum to ensure better state testing results (Alberts, 2004). State testing can be useful, as long as it is not about students memorizing facts but teaching students to critically think about important issues (Marincola, 2006). With there being a need to increase science literacy, there is always room for incorporating new approaches when teaching science. Science taught at the high school level is often abstract and lacking relevance, which could be contributing to the lack of scientific literacy (Conroy et al., 1999; Shelley-Tolbert et al., 2000).

Historically, career and technical education courses (agriscience education courses) are known for teaching industry specific skills that prepare students for employment (Gordon, 2008). Similarly, students recognize science concepts taught within an agricultural context. Agriscience programs offer an opportunity for students to apply skills and knowledge learned through science courses to real-life situations. This is why agriculture programs integrate science into their courses (Castellano et al., 2003; Israel al., 2012). Agriscience helps students to learn STEM concepts and to utilize those skills through practical applications (Chiasson & Burnett, 2001; Mabie & Baker, 1996; Myers et al., 2009). STEM concepts have been taught in many agricultural content areas, including horticulture and floriculture (Ferand et al., 2020) and animal science (Harmon et al., 2023).

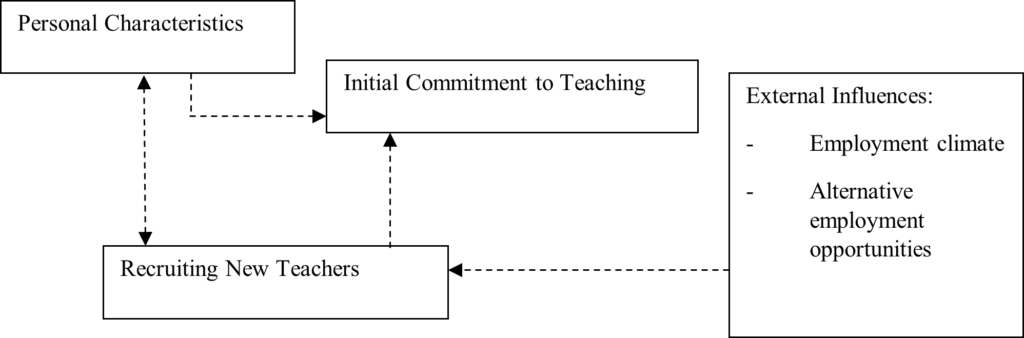

However, at the secondary school level, guidance counselors are often the gatekeepers to a student’s future. One of their functions is to assist students throughout their high school career, and to help them decide, plan, and pursue post-secondary education (Rowe, 1989). College personnel see high school guidance counselors as individuals who have significant influence on students as they transition from high school (Rowe, 1989). Counselors tend to advise students toward conventional educational choices more than vocational education choices (Lewis & Kaltreider, 1976). While guidance counselors help students identify educational and career paths that are suited to their interests, there is often a low counselor to student ratio. This can be an issue for availability.

Counselors cannot be experts in every occupational area, which is why consultation will have to come from more than one person (Johnson & Brown, 1977). If counselors do not have information about the agriculture program in the school, they may not be able to advise correctly for that department. Communication between agriculture teachers and guidance counselors is important for students to provide the information they need to choose courses. Counselors may not be familiar with the science that is present in high school agriscience courses. As a result, agricultural educators need to highlight the significance of science in their courses to improve perceptions of the science that is taught in agriscience courses.

Theoretical Framework

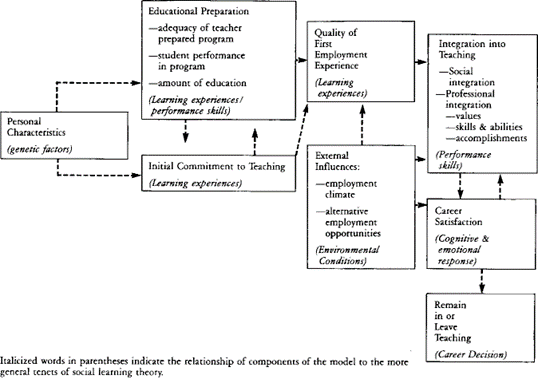

Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (TPB) was used as the theoretical framework for this study (1991). The TPB model indicates that a person’s attitude, their subjective norms, and their perceived behavioral control impacts their intentions, which then impacts their behavior (Ajzen, 1991). For our study, we are looking at the behavior of teaching science through agriscience courses. Ajzen’s TPB allows us to examine the guidance counselors attitudes and perceptions of teaching science through agriscience.

Purpose and Research Questions

In 1990, the Carl Perkins Act was amended to emphasize the integration of academic skills and knowledge to a career and technical education setting (Gordon, 2008). This movement focused on utilizing agriscience courses to meet learning outcomes (Stern & Stearns, 2006) that are academic in nature. The purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of high school guidance counselors across the state of Nebraska regarding the science that is present in high school agriscience courses. Understanding guidance counselors’ perceptions of the science present in high school agriscience courses could help agriscience instructors to successfully highlight the significance of science in their courses and to improve perceptions of the science that is taught in agriscience courses. The following research question guided this study: How do high school guidance counselors perceive the science that is taught in agriscience?

Methods

This study is qualitative in nature. According to Creswell (1998), a qualitative study allows for the researchers to better understand what is happening. More specifically, Merriam’s basic or generic qualitative methodology was used for this study (1998). The basic or generic methodology allows the researcher to provide a detailed description, adhere meaning to the data, and organize the data into themes (Merriam, 1998).

The guidance counselors consisted of both male and female guidance counselors that worked in the state of Nebraska. To determine which guidance counselors would be asked to participate, the “School & Teacher Directory” page was referenced on the Nebraska Department of Education’s Career Education Agriculture, Food, and Natural Resources website. From the list of all schools in Nebraska offering agriscience courses, a list of the high school guidance counselors from those schools were made. An email was sent to each of them asking if they were willing to participate. After each guidance counselor agreed to participate, a follow up email containing an Institutional Review Board approved consent form was sent to each Guidance Counselor that was willing to participate. Once the participants confirmed their consent to participate, interviews were scheduled and conducted via Zoom, lasting between 45-60 minutes each. Ten guidance counselors across Nebraska participated in the study.

A semi-structured interview approach was used to ask probing questions based on participant responses. In accordance with Creswell (1998) each interview was recorded and transcribed for data analysis. The data was analyzed by the researchers using thematic data analysis. Thematic data analysis allowed for the data to be grouped into smaller chunks for the researchers to focus on recurring words and phrases found in the data (Grbich, 2007). The block and file approach was also used to delineate words and phrases found in the data (Grbich, 2007). The recurring words and phrases were categorized together into themes. The data was coded by hand through a process of color-coding words and phrases that were similar in nature. The color coding allowed for the data to be grouped together and for themes to emerge.

In qualitative research, it is important to address trustworthiness (Dooley, 2007). In order to achieve credibility, triangulation amongst the researchers was used. Three of the researchers analyzed the data and came to agreement on the themes that emerged from the data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Member checking was also used to help ensure credibility (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). During the interviews, the guidance counselors were given the opportunity to verify the meaning of what was stated. The researcher directly asked the participants for clarification and if they were accurately interpreting what was said. In order for this study to be replicated and to account for dependability and confirmability, the researchers kept an audit trail by writing down notes to trace the decisions that were made throughout the research process (Dooley, 2007). Transferability was ensured by provided a description of the context.

The researchers in this study all have experience working in the field of agricultural education. Four of the researchers have experience teaching high school agriculture and two of the researchers are professors of agricultural education. Additionally, one researcher has a background as an animal science professor and has experience facilitating professional development for high school agriculture teachers. Three of the researchers have multiple publications focused on science literacy and integrating science into the agriculture classroom.

Findings

From the interviews, six themes emerged: (a) disagreement about science credit for agriscience courses, (b) superficial knowledge of agriscience courses, (c) real world connections, (d) reasons for student placement in agriscience courses, (e) lack of high school agriscience experience, and (f) agricultural connections.

Disagreement about Science Credit for Agriscience Courses

The guidance counselors interviewed agreed regarding the real-world applications of science in agriscience courses. The most practical science is happening in those courses. The science there is “absolutely real and useful.” While seven counselors interviewed believe science credit should be awarded for agriscience courses, others were not as receptive. Guidance counselors want agriscience instructors that are highly qualified in the area of science. Agriscience courses “need real science” in them, although there is the idea that agriscience is already integrated into science courses. If the agriscience instructor is accredited to teach science, students taking those courses should be able to receive science credit, especially with a perceived shortage of science teachers across our state.

In some cases, science credit is available for some courses. One guidance counselor who believed agriscience courses should count for science credit said specifically, “Agriscience, Plant Science, Animal Science and Environmental Science are ones that could be taken for science credit.” Of course, there are differences in perceptions of the science being taught in agriscience programs compared to traditional science courses. One counselor said, “Personally, I feel that’s just as much as what is being taught in a regular science course. I would have to say that they should be able to receive credit.” Another counselor disagreed. “The science teacher thought it should be more rigorous.”

Despite the shared belief that agriscience courses apply science principles to real world experiences, those experiences may not be traditional enough to fulfill normal expectations for a science class. One counselor said that agriscience courses not counting for science credit “comes down to the fact that they really don’t do and didn’t have the labs [that] would probably need to count as a science credit.” That counselor went on to say that, “There is definitely science in the ag courses, but it’s not every day.”

While guidance counselors felt the most practical and real science is happening in agriscience courses, the idea of giving science credit for agriscience courses was not as easily agreed upon. Interestingly, a perceived lack of rigor or laboratories was enough to question whether the science in agriscience courses is practical or real enough to equate to science credit.

Superficial Knowledge of Agriscience Courses

All the guidance counselors involved in this study played a part in helping students schedule their courses. Even with a large role in guiding students through class scheduling, their knowledge of the agriscience courses offered is largely superficial. Only one of participants were knowledgeable about agriscience courses offerings. The remaining participants relied primarily on course descriptions. The participants all had course descriptions that they review with students when scheduling courses. One participant used the course description to provide guidance if a student asked for assistance. Another participant lets the student read the descriptions to decide on their own. If, after reading the description, the student is still unsure, he or she is advised, “We won’t know unless you try.”

In addition to course descriptions, guidance in class selection is dependent on additional factors. What grade level “can take” each class is used with course descriptions, so grade appropriateness is important. Options within the schedule were also factor. Largely, though, course descriptions were the most common resource used by the guidance counselors in helping students select courses.

Real World Connections

All guidance counselors surveyed addressed the connections between agriculture and the real application of science. A common theme that emerged was the real-world connections of science in agriculture. As one guidance counselor pointed out, the connection to agriculture makes the core subject material more real. By having a link to real-world experiences, to some degree, agriscience courses give students an opportunity to look at science differently.

The importance of cross-curriculum in agriscience is a noted benefit. From the interviews, agriscience courses drew connections to mathematics, English, and business courses, in addition to science. One guidance counselor twice pointed out how highly connected math, science, and communication skills are in agriculture. That teacher went on to say that “there are a lot of realities and skills that are connected with agriscience that will be utilized by people across many different areas in life.” Agriscience courses provide students with real world examples when and how science concepts are use. One guidance counselor said, “There seems to be a connection everywhere to agriculture.” The hands-on application and connections to real experiences in agriscience courses help students buy into and apply science concepts that students need to know.

Reasons for Student Placement in Agriscience Courses

The recommendations by guidance counselors for elective courses were based on student interest, perceived skill level, and future plans. Class recommendations are individualized and depend on what students tell them. The options of courses, then are based on the students’ expressed interests. If students have passion, interest and skill level in a specific area, then the student is advised to take that particular course. If they are not interested in a recommended area, different electives are suggested.

Students with an interest in agricultural careers are highly encouraged by their guidance counselors to take agriscience courses. From the interviews, agriscience courses are recommended to students with interests specifically in veterinary science and technology, agronomy, farming, agribusiness, landscaping, lawn care, gardening, welding, automotive, diesel mechanics, and ranching. Two of the interviewed guidance counselors recommend agriscience courses to students who may not have agriculturally related career goals or are unsure of their interest in agriculture. One of the two said that the type of students who typically enrolls in agriscience courses are “those who aren’t sure they have an interest and those who want to see if they have an interest.” There is also an expressed potential for those students to enjoy agriscience courses and take additional agriscience courses. Another guidance counselor noted the potential benefits from taking an agriscience course not directly related to their career goals. “Even if they are not going to use that in their future college career, I still think there are benefits to be gained from being in those courses.”

Lack of High School Agriscience Experience

Of the 10 guidance counselors interviewed, only one was enrolled in agriscience courses as a high school student. Five attended high schools that did not offer agriscience courses. One counselor responded saying, “It was not encouraged. I didn’t think I could.”

Agricultural Connections

All of the respondents to the interviews had personal experiences or direct family connections to agriculture. Seven of the respondents grew up on farms, one respondent’s father farmed on the side while owning and operating a grain elevator, and one cited her experiences on her grandparents’ farm growing up. Two of the respondents are still personally involved in agriculture by raising livestock and one is involved in a family farming operation. One interviewee stated that “agriculture has always been a part of my life.” The responses by the guidance counselors interviewed showed some level of connection to agriculture through personal experiences or connections to family growing up.

Conclusion

Guidance counselors assist students throughout their school career by helping decide, plan and pursue post-secondary education, particularly by making recommendations for course enrollment. They are the gatekeepers to students’ futures. Guidance counselors’ jobs are important for students in finding a path that is suitable for their interests. Counselors tend to avoid advising students to enroll in vocational courses (Lewis & Kaltreider, 1976), and this study of high school counselors showed that the recommendations by guidance counselors for elective courses are based on student interest, perceived skill level, and future plans that are largely based on what the student tells them or the students’ expressed interests.

This study found that students with an interest in agricultural careers are highly encouraged by their guidance counselors to take agriscience courses. However, what about students who may be unaware of the possibilities in agriculture? Even though the guidance counselors in this study have connections and experiences in agriculture, their knowledge of specific agriscience courses is largely superficial and their own experiences in high school agriscience courses were limited. By having a superficial knowledge of agriscience courses, guidance counselors are missing opportunities to expose new students to opportunities through agriculture. This means that potential students could miss the opportunity to learn about STEM through animal science courses (Harmon et al., 2023) and floriculture and horticulture courses (Fernand et al., 2020). For example, real world skills learned in animal science could translate to skills in the medical field, but students may miss the opportunity to be exposed to those real experiences by not being advised to take agricultural courses. By being specific about the applicable science skills in agriscience courses, guidance counselors can find parallels that translate to skills outside of agriculture.

Even though their role in guiding students to specific courses, counselors are largely dependent on course descriptions provided by the instructor. Counselors cannot be “experts” in every occupational area, which is why consultation from agriscience instructors is critical. If counselors do not have information about the agriculture program in the school, they will not be able to advise correctly for that department. Agriscience instructors need to take a more active role in providing specific necessary information about their courses to appropriately assist guidance counselors in helping students with the selection of their courses. Agriscience teachers could work with their students to develop short YouTube videos that demonstrate the science that is being taught in the agriscience classroom. These YouTube videos could help the guidance counselors better understand the agriscience classroom and the videos could also be shared with students as a recruitment effort. The YouTube video should highlight the STEM concepts taught within agriscience courses. If more students enrolled in agriscience courses, more students would be exposed to courses that use applied STEM concepts, which could help remedy the issue that Conroy et al., 1999 and Shelley-Tolbert et al., 2000 raised with the abstractness of traditional science courses.

Guidance counselors perceived a lack of rigor regarding science in agriscience courses. When examined through Ajzen’s TPB (1991), the guidance counselors do not have a positive perception of the rigor associated with the science being taught. Therefor the guidance counselors’ attitude toward the science being taught through agriscience is less than positive. Because guidance counselors were reliant on course descriptions in helping students select their courses, agriscience course descriptions should be enhanced to showcase the science in agriscience. Agriscience courses with “science” incorporated into the name are perceived to be more advantageous to fulfilling science credits. To fulfill science requirements, guidance counselors need to see the connection to traditional science courses. Current science standards should be used to show that specific science principles are being taught. Related career areas, both related to agriculture and outside of agriculture, should also be listed. Course descriptions should be complete enough to benefit the guidance counselor, the agriscience instructor and the student. By clearly making the connection between traditional sciences course and agriscience courses, more students may enroll expanding the agriscience teachers’ opportunity to successfully help students improve their standardized test scores, which could contribute to improved high school students math and science scores in the United States (Kuenzi, 2008).

This study of guidance counselors identified the common view of the “realness” of science and cross-curricular benefits of agriscience courses. Laboratory experiences are an important part of science education. In regard to agriscience courses, there appears to be ambiguity in regard to what constitutes a laboratory experience. Guidance counselors see the real experiences and hands on approach to agriscience as advantages to learning in agriculture. Agriscience teachers need to be proactive in selling those experiences as being as beneficial as labs in a science classroom. Agriscience teachers should make it a priority to invite guidance counselors to observe and participate in laboratory experiences that have practical applications. This will let the guidance counselors experience the science that is being taught and it will allow for further discussion between agriscience teachers and guidance counselors. Additionally, it is the practical application in agriscience that helps students to learn and use STEM concepts (Chiasson & Burnett, 2001; Mabie & Baker, 1996; Myers et al., 2009).

With an increased importance in science literacy, there is a need for new approaches to teaching science. Agriculture programs have science integrated into their courses and students are able to recognize science concepts taught through an agricultural context (Chiasson & Burnett, 2001; Mabie & Baker, 1996; Myers et al., 2009). Agriscience programs offer opportunities for the skills and knowledge learned in science courses to be linked directly to authentic applications, which is why agriculture programs have science integrated into their courses (Castellano et al., 2003). Students are able to learn STEM concepts and be able to see those skills through practical applications and contextualizing science concepts. Inquiry-based instruction is one teaching method being used in science standards. Inquiry-based teaching methods have been found to enhance a student’s ability to conduct experiments and to help them gain a better understanding of the process of scientific inquiry (National Research Council [NRC], 2007). Teachers should purposefully select methodologies when integrating STEM content into the context of agriculture (Baker et al., 2014). Although guidance counselors agree about the realness of science in agriculture, they are conflicted on whether that realness is enough to fulfill the requirements of a traditional science class. Science is a core principle of agriscience courses. Agriscience programs offer opportunities for the skills and knowledge learned in science courses to be linked directly to authentic applications, which is why agriculture programs have science integrated into their courses (Castellano et al., 2003).

Student enrollment in agriscience courses is largely dependent on the role guidance counselors play in advising those students. While guidance counselors may have connections to agriculture and see real world connections to principles of agriscience, their experience with and knowledge of agriscience courses is largely superficial. The decisions they make for student placement is largely dependent on student interest and provided course descriptions. While guidance counselors see the real-world applications in agriscience courses, specific connections to science principles must be drawn for them to qualify for science credit. For agricultural educators to depend on enrollment in agriscience courses and for agriscience students to receive science credit, agriscience instructors must work with guidance counselors and provide all of the necessary information. Agriscience teachers need to be instrumental in educating guidance counselors about what they are currently doing in their programs to show them the connection between agriscience and science standards. This will help to show guidance counselors the importance of agriscience courses and how they impact academic learning. Agriscience education professionals understand how agriscience courses improve and enhance students’ academic achievements in the field of science (Enderlin & Osborne, 1992, Enderlin et al., 1993; Roegge & Russell, 1990; Whent & Leising, 1988) and how science is integrated into agriscience courses. Agriscience teachers should invite guidance counselors to come to their classrooms and participate in some learning activities that demonstrate how science is used in agriscience courses. Additionally, brochures/handouts that emphasize the science components within agriscience should be developed and left with the guidance counselors. The brochures/handouts could be used with the students when the guidance counselor is helping the student select courses.

Future research needs to be conducted in this area. Research has clearly documented that STEM concepts are effectively taught through agriscience (Chiasson & Burnett, 2001; Mabie & Baker, 1996; Myers et al., 2009). Future research should be done to see if guidance counselors in other states have similar perception. An investigation focused on what agriscience teachers are currently doing to educate and promote their agriscience courses with their guidance counselors would allow us to better understand what needs to be done in the future. Additionally, there may be some agriscience teachers doing a phenomenal job educating and promoting their agriscience courses with their guidance counselors.

References

Alberts, B. (2004, April 19). A world that banks on science. National Academy.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t

Castellano, M., Stringfield, S., Stone, J. R., III. (2003). Secondary career and technical education and comprehensive school reform: Implications for research and practice. Review of Educational Research, 73(2), 231-272. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543073002231

Chiasson, T. C., & Burnett, M. F. (2001). The influence on enrollment in agriscience courses on

the science achievement of high school students. Journal of Agricultural Education,

42(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2001.01061

Conroy, C. Trumbull, D., & Johnson, D. (1999). Agriculture as a rich context for teaching and learning, and for learning mathematics and science to prepare the workforce of the 21st Century [White paper]. National Science Foundation.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications.

Dooley, K. E. (2007). Viewing agricultural education research through a qualitative lens. Journal of Agricultural Education, 48(4), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2007.04032

Enderlin, K. J., & Osborne, E. W. (1992). Student achievement, attitudes, and thinking skill attainment in an integrated science/agriculture course. Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual National Agricultural Education Research Meeting, 37-44. St. Louis, MO.

Enderlin, K J., Petrea, R. E., & Osborne, E. W., (1993). Student and teacher attitude toward and performance in an integrated science/agriculture course. Proceedings of the 47th Annual Central Region Research Conference in Agricultural Education. St. Louis, MO.

Ferand, N. K., DiBenedetto, C. A., Thoron, A. C., & Myers, B. E. (2020). Agriscience Teacher Professional Development Focused on Teaching STEM Principles in the Floriculture Curriculum. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(4), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.04189

Gordon, H. R. (2008). The history and growth of career and technical education in America. Waveland Press.

Grbich, C. (2007). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Sage.

Harmon, K., Ruth, T., Reiling, B., Conner, N. W., & Stripling, C. T. (2023). Predicting teachers’ intent to use inquiry-based learning in the classroom after a professional development. Advancements in Agricultural Development, 4(3), 90–102. https://doi.org/10.37433/aad.v4i3.345

Harrington, E. G. (2015, Summer). Science and technology resources on the internet. http://istl.org/15-summer/internet.html

Hom, E. J. (2014, February). What is STEM education? https://www.livescience.com/43296-what-is-stem-education.html

Israel, G., Myers, B., Lamm, A. & Galindo-Gonzalez, S. (2012). CTE students and science achievement: Does type of coursework and occupational cluster matter? Career and Technical Education Research. 1, 3-20(18). https://doi.org/10.5328/cter37.1.3.

Johnson, R. W. & Brown, R. A. (1977). Who provides agricultural career information? Journal of Agricultural Education, 18(1), 17-21. https://doi.org/10.5032/jaatea.1977.01017

Kennedy, B. (2024). Most americans think U.S. K-12 STEM education isn’t above average, but test results paint a mixed picture. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/04/24/most-americans-think-us-k-12-stem-education-isnt-above-average-but-test-results-paint-a-mixed-picture/

Kuenzi, J. J. (2008). Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education: Background, federal policy, and legislative action (Government Report). Congressional Research Service.

Lewis, M. V. & Kaltreider, L. W. (1976). Attempts to overcome stereotyping in vocational education. Institute for Research of Human Resources.

Lincoln, Y. S. & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Mabie, R., & Baker, M. (1996). A comparison of experiential instructional strategies upon the science process skills or urban elementary students. Journal of Agricultural Education, 37(2), l–7. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1996.02001

Marincola, E. (2006). Why is public science education important? Journal of Translational Medicine, 4. http://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-4-7

McLure, G., & McLure, J. (2000). Science course taking, out-of-class science accomplishments, and achievement in the high school graduating class of 1998. ACT Research Report Series 2000.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

Miller, J. D. (2010). The conceptualization and measurement of civic scientific literacy for the twenty-first century. In J. Meinwald & J.G. Hildebrand (Eds.), Science and the educational American: A core component of liberal education. American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 136, 241-255.

Myers, B. E., Thorn, A.C. & Thompson, G. W. (2009). Perceptions of the national agriscience teacher ambassador academy toward integrating science into school-based agricultural education curriculum. Journal of Agricultural Education, 50(4), 120–133.

http://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2009.04120

National Commission on Excellence in Education (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. The Elementary School Journal, 84(2), 113-130.

Roegge, C. A. & Russell, E. B. (1990). Teaching applied biology in secondary agriculture: Effects on student achievement and attitudes. Journal of Agricultural Education, 31 (1), 27-31. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.1990.01027

Rowe, F.A. (1989). College students’ perceptions of high school counselors. The School Counselor, 36, 260-264. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23903412

Shelley-Tolbert, C. A., Conroy, C. A., & Dailey, A. L. (2000). The move to agriscience and its impact on teacher education in agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 41(2), 51-56. http://doi.org/10.5032/jae2000.04051

Stern, D. & Stearns, R. (2006). Multiple perspectives on multiple pathways: Preparing California’s youth for college, career, and civic responsibility. http://idea.gseis.ucla.edu/projects/multiplepathways/index.html

Whent, L. S., & Leising, J. (1988). A descriptive study of the basic core curriculum for agricultural students in California. Proceedings of the 66th Annual Western Region Agricultural Education Research Seminar. Fort Collins, CO.