Authors

Will Doss, University of Arkansas, wd009@uark.edu

Christopher M. Estepp, University of Arkansas, estepp@uark.edu

Donald M. Johnson, University of Arkansas, dmjohnso@uark.edu

Kobina Fanyinkah, University of Arkansas, kobinaf@uark.edu

Abstract

Small engine maintenance and repair is a topic in which school-based agricultural education teachers lack technical skills and need instructional planning professional development. At the college level, this topic is taught to preservice SBAE teachers and serves as example that can be used at the secondary school level. To maximize the quality of instruction in this area, a critical evaluation of procedures used to teach small engine concepts at the post-secondary level was conducted. This study examined three factors regarding instruction in a small engines course: student knowledge, interest, and self-efficacy. A quasi-experimental design was used to compare pre and post knowledge levels, perceived self-efficacy, and subject matter interest of participants on the topics of precision measurement and carburetor part identification and function. Participants received instructional treatments designed based on situated learning theory related to each specific topic. Having two different topics allowed for an internal replication of the study. We found the precision measurement instructional treatment resulted in a significant increase in knowledge scores and slight decreases in self-efficacy and interest. For the carburetor topic, there were increases in knowledge, though not significant, and decreases in measured perceived self-efficacy and interest. For the internal replication, the direction of changes in self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge were the same across both designs and with both topics, however, significance was not always the same. Instructors at the post-secondary level and secondary SBAE teachers could use methods described in this study to teach precision measurement and carburetor part identification and function if their goal is to increase knowledge of these topics. We recommend conducting further research to identify ways to maintain or increase self-efficacy and interest while gaining knowledge. Additional testing of instructional designs using situated learning theory in agricultural mechanics and other agricultural topics is also encouraged.

Introduction

Small engine maintenance and repair is a subject many SBAE teachers have been expected to teach; however, it is the least taught agricultural mechanics subject at the post-secondary level (Clark et al., 2021). Despite not being taught often, those who took a college course in small engine agricultural mechanics were associated with being more competent in teaching small engine repair, highlighting a benefit of the course (LaVergne et al., 2018). However, due to the lack of instruction on small engine maintenance and repair, it is an area where current SBAE teachers lack technical skills (Wells & Hainline, 2021) and was identified as a topic where SBAE teachers need professional development in instructional planning and evaluation (Hainline & Wells, 2019; Peake et al., 2007). SBAE teachers lack depth in their instruction on small engines and believe competencies related to small engines are only somewhat important (Rasty & Anderson, 2025). Additionally, prior research found preservice teachers had poor content knowledge related to small engines, affecting their ability to troubleshoot engine problems and likely the quality of instruction they will provide in their future classrooms on the topic (Blackburn et al., 2014).

Quality of instruction is an important element of student learning and ultimately career-readiness (National Research Council [NRC], 2000), particularly for preservice school-based agricultural education (SBAE) teachers (Shoulders et al., 2013). Courses on small engines have been used to assess the quality of instruction from several different perspectives. At both the secondary and post-secondary levels, students taking a course in small engines had higher success rates with small engine troubleshooting when using think-aloud pair problem solving compared to those who did not use the learning technique (Pate & Miller, 2011; Pate et al., 2004). The effects of cognitive learning styles on the ability to solve problems related to engine troubleshooting has also been tested (Blackburn & Robinson, 2017; Blackburn et al., 2014). These studies indicated students with a more innovative cognitive style are less likely to hypothesize correctly when troubleshooting small engine problems compared to students with a more adaptive learning style. Other researchers have examined the positive impact on perceived importance and ability to teach small engine repair skills from offering a two-day professional development event for teachers (Anderson et al., 2022) and how using a small engine diagnostics mobile app can improve competency and knowledge in small engine troubleshooting (Valdetero et al., 2015).

Because of expectations placed on SBAE teachers to teach small engines and the minimal instruction received, the need existed to maximize the quality of instruction in this area at the University of Arkansas. A critical evaluation of procedures used to teach small engine concepts at the post-secondary level was needed to identify best practices for increasing the quality of instruction preservice SBAE teachers receive in small engine courses.

Literature Review/Theoretical Framework

This study examined three important factors regarding instruction in a small engines course: student knowledge, interest, and self-efficacy. According to the literature, using diverse instructional methods impacts the effectiveness of teachers, quality of instruction, and students’ knowledge gains (NRC, 2000; Rosenshine & Furst, 1971). While instruction in agricultural mechanics has historically relied upon varying hands-on, student-centered methods taught in the classroom or laboratory (Newcomb et al., 2004; Talbert et al., 2022), few studies have examined student learning in agricultural mechanics using experimental designs. More studies have explored students’ perceptions, and when tasks are perceived as difficult, student knowledge gains, student interest, and self-efficacy can be negatively affected (Niemivirta & Tapola, 2008). Conversely, knowledge gains and increased student performance have been related to higher self-efficacy (Bailey et al., 2017). Interest, however, was not always related to task performance or knowledge gain (Hackett & Campbell, 1987; Nuutila et al., 2021). Related studies have shown that knowledge gains are not substantially impacted by either student interest or self-efficacy, it was likely the instructor who played a larger role through quality instruction (Guo et al., 2020).

Findings from the literature on the effects of instruction on knowledge, interest, and self-efficacy were mixed. To better understand how these variables relate, we can consult the expectancy-value theory (EVT). Rooted in Atkinson’s (1957) seminal work, modern EVT posits a student’s level of success or achievement of a task can be influenced by their beliefs about how well they will do on the task and the extent to which they value the activity (Wigfield, 1994; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Expectancy, or belief about how well students will do on an upcoming task, is often linked to Bandura’s self-efficacy construct in which the more positive one’s self-efficacy beliefs are toward a particular task, the greater the influence on one’s expectation for success (Wigfield et al., 2021). Although Wigfield and Eccles (2000) argued self-efficacy and expectancy are not exactly equal because self-efficacy evaluates the present and expectancy refers to future performance, self-efficacy measures are very similar and are often used, especially for task-specific situations.

In addition to expectancy, values contribute to achievement and as such have been categorized into four types: attainment value, intrinsic value, utility value, and cost (Eccles, 2005). According to Eccles, attainment value is the personal importance of doing well on a task because it is linked to an individual’s personal and social identities. Intrinsic value is the enjoyment one gets from performing the activity or their subjective interest in the activity. Utility value refers to how individuals believe a task relates to current and future goals. Finally, cost is what one has to give up or negatively experience in order to engage in the activity. Overall values related to doing an activity are collectively shaped by all four areas previously described and provide for the reason one does an activity (Mathew et al., 2022).

An individual’s expectancy and values both interact and can be used to predict academic achievement (Mathew et al., 2022). This study measured achievement through knowledge scores on a quiz, intrinsic values were evaluated with an interest scale, and expectancy was estimated with a self-efficacy scale. Our measures were topic specific on two different lessons taught in a college level small engines course. Due to the limited size of our accessible population, we did not attempt to predict achievement, rather we were interested in observing changes in expectancy, value, and achievement after an instructional intervention.

Situated learning theory (SLT) served as the theoretical model for instructional design for the lessons taught in this study (Bell et al., 2013; Green et al., 2018). According to SLT, the learning environment can be composed of three different areas: the use of a constructivist learning approach, teaching and evaluation in an authentic context, and the use of social interaction to enhance learning (Bell et al., 2013; Green et al., 2018). SLT highlights the need for all these areas to be present to increase long-term learning (Bell et al., 2013; Green et al., 2018). To achieve the purpose of this study, we used a constructivist approach by designing lessons where students’ pre-lesson knowledge was assessed and then built upon using varying instructional methods. Laboratory activities served as an authentic context for learning and evaluation to occur. As part of evaluation in an authentic context, students used a reflection video to self-evaluate their knowledge on lesson topics. These videos allowed students to evaluate their own performance and recall what they did during a task by providing real-time, vivid, and physical evidence of their performance (Arikan & Bakla, 2011; Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012). Social interaction was incorporated in the learning environment by pairing students to work together on various activities and videos. The use of cooperative learning has the potential to deepen understanding of course materials, and hence was chosen as a key component in instructional design (Gregg & Bowling, 2023).

Purpose and Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess the effectiveness of an instructional treatment using video reflection on student learning. The objectives that guided the study were:

- Compare pre and post knowledge levels, perceived self-efficacy, and subject matter interest of participants on the topic of precision measurement.

- Compare pre and post knowledge levels, perceived self-efficacy, and subject matter interest of participants on the topic of carburetor part identification and function.

Methods

The population of this study was undergraduate students in the Small Power Units/Turf Equipment course at the University of Arkansas (N = 32) in the spring 2023 semester. The course was designed for junior level students and was focused on concepts related to small engine theory, operation, and maintenance in the context of small turf equipment. After IRB approval was granted, two course topics were selected for assessment: precision measurement and carburetor part identification and function. These two topics were chosen because the course instructors identified them as topics in which students historically have had difficulty understanding. The evaluation of the effectiveness of a new design for teaching these topics was desired.

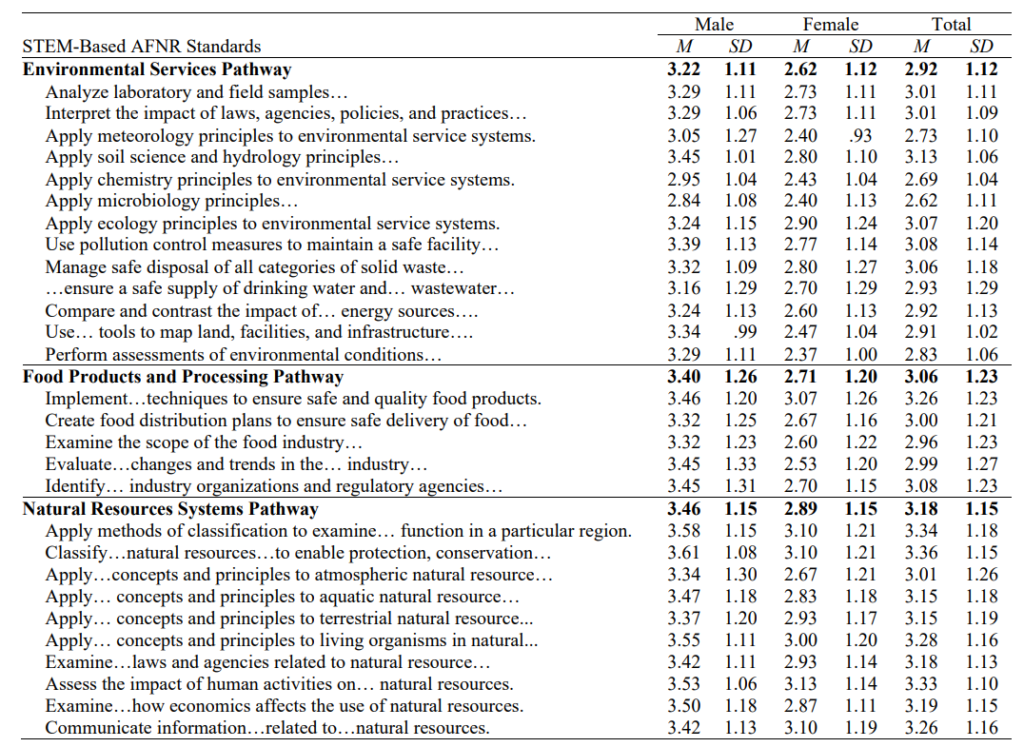

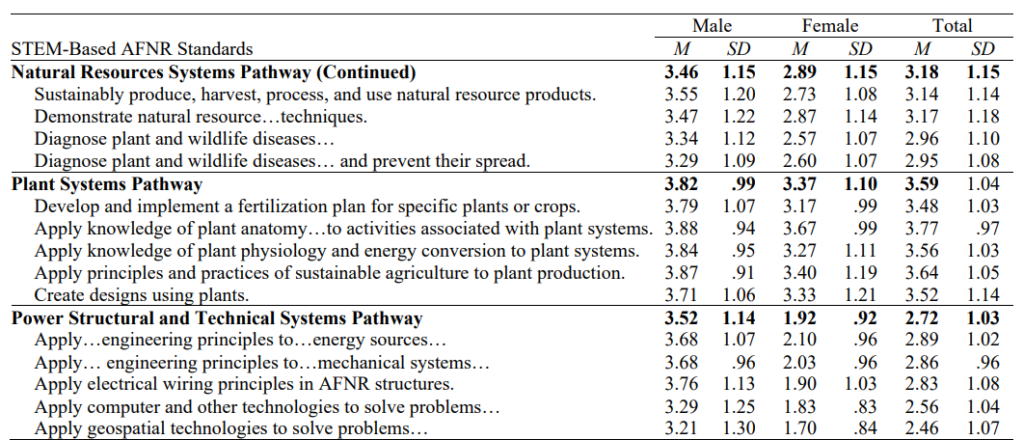

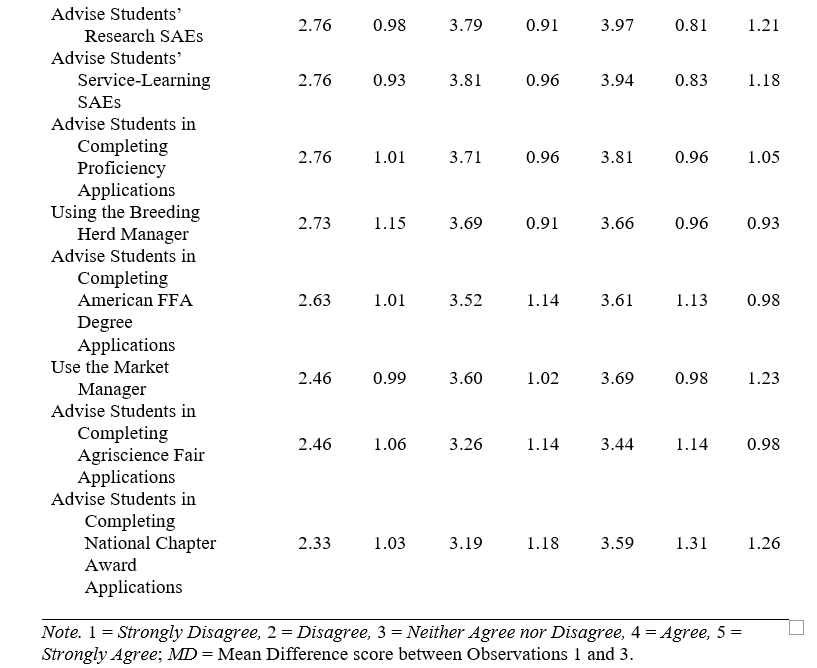

This quasi-experimental study utilized two Campbell and Stanley (1963) designs (Figure 1) including a one-group pretest-posttest (design 2) and a separate-sample pretest-posttest (design 12). These designs were chosen over an experimental design because participation in the treatment was a course requirement for all students to ensure fairness, preventing the use of random assignment required for a true experimental design. Design 2 compared pretest (O1) and posttest (O2) scores for control group participants only. Design 12 compared pretest scores (O1) of the control group to posttest scores (O2) of the treatment group. According to Campbell and Stanley (1963), design 12 controls for all threats to external validity and all threats to internal validity except for history, maturation, and the interaction of the two. However, we did not consider history or maturation a threat due to the short duration of this study. Design 2 served as internal replication where the entire study was replicated by completing the process with the topic of precision measurement and then with carburetor part identification and function.

Figure 1

Research Design with Statistical Comparisons for Designs 2 and 12 (Campbell & Stanley, 1963)

The 20-item instrument used for pretest and posttest measures for both instructional topics included three sections: perceived subject matter self-efficacy (nine items), subject matter interest (11 items), and subject matter knowledge (5 items). We chose to use the self-efficacy scale from the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ) (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990) because it was designed to measure subject-specific self-efficacy and had a reported reliability of α = .89. Sample items included “I expect to do very well on this topic” and “Compared with other students in class I think I know a great deal about this topic.” Items were rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = not at all true of me to 7 = very true of me). Subject matter interest was measured with the general interest scale from the Gable-Roberts Attitude Toward School Subjects (GRASS) instrument and had a reported reliability of α = .94 (Gable & Roberts, 1983). Sample items included “The subject fascinates me” and “I look forward to my class in the subject.” Items for the general interest scale were rated from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

The measure for subject matter knowledge was a five-question, multiple choice quiz developed by the research team with possible scores ranging from zero to 100. While a five-question quiz was chosen to remain consistent with other quizzes given throughout the semester in the course. Questions were created to assess instructional objectives for each topic. For the instructional topic of precision measurement, sample questions included: “Which tool would be most appropriate for measuring piston ring gap?” and “Determine the micrometer reading for the pictured 2”-3” micrometer.” For the instructional topic of carburetor part identification and function, sample questions included “Which of the following carburetor parts is the arrow pointing to in the illustration below?” and “What is the part of the carburetor that carries the fuel from the bowl to the venturi called?” Each question included four possible answer choices. Pre-test and post-test instruments were identical for both stages of measurement. Pretests were administered one class day before the instructional treatment, followed by two periods of classroom/laboratory instruction, and then a posttest the class day after treatment was completed, resulting in two weeks between the pretest and posttest.

The instructional treatment for precision measurement included a short demonstration and discussion of precision measurement tools, a laboratory hands-on guided practice activity measuring engine components, a homework sheet to practice reading micrometers, and a video reflection where students worked in pairs to explain the purpose, identify parts, and demonstrate how to use micrometers, telescoping gauges, and feeler gauges. The instructional treatment for carburetor part identification and function consisted of a one-hour class lecture on fuels and combustion chemistry, a one-hour class lecture on carburetor components, functions, and theory, one lab activity with a complete carburetor tear down, inspection, and reassembly, and a video reflection where students worked in pairs to explain the overall function of a carburetor, identify carburetor parts and their specific functions, and explain how fuel and air flow in the carburetor.

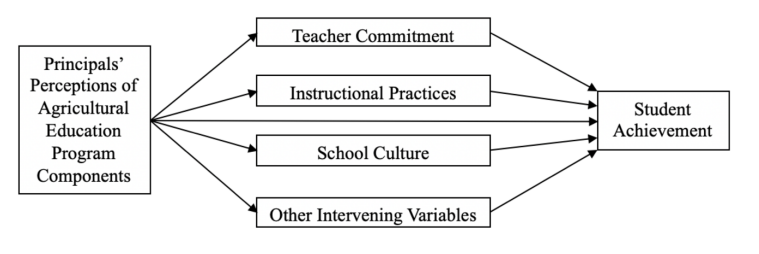

To establish validity for the knowledge scales, two members of the research team familiar with course content and assessment design created questions aligned with content learning objectives. Multiple choice questions were modified from those used in the course textbook and existing test materials already developed for the course. The team worked together to ensure all questions were written at the “remember” level of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Anderson et al., 2001). To determine reliability of both the precision measurement and carburetor instruments, post hoc reliability coefficients were calculated for pretest (n = 16) and posttest (n = 32) scores (Table 1). Alpha coefficients for the self-efficacy and interest constructs were acceptable (Taber, 2018). The reliability of the knowledge construct was low but acceptable, except for the posttest reliability for precision measurement. According to Paek (2015) low reliability coefficients on knowledge scales can be associated with guessing, a possibility with students in the course. Additionally, the low number of items on the quiz likely contributed to reduced reliability.

Table 1

Construct Scale Reliabilities by Topic

| Precision Measurement | Carburetors | ||||

| Variable | Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | |

| Self-efficacya | .89 | .94 | .91 | .97 | |

| Interesta | .92 | .96 | .90 | .94 | |

| Knowledgeb | .59 | .41 | .77 | .50 | |

| acoefficient alpha, bKR-20. | |||||

Data from this study were collected through paper copies of the pretests and posttests administered in class. A member of the research team scored knowledge sections and entered all data for each student into a spreadsheet. Frequencies and percentages were used to describe participant demographics while means and standard deviations were used to describe self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge. Paired-samples t-tests were used to compare pretest and posttest scores for Design 2. To compare pretest and posttest constructs for Design 12, a MANOVA was conducted with post hoc comparisons in SPSS v.28. Significance was established a priori at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

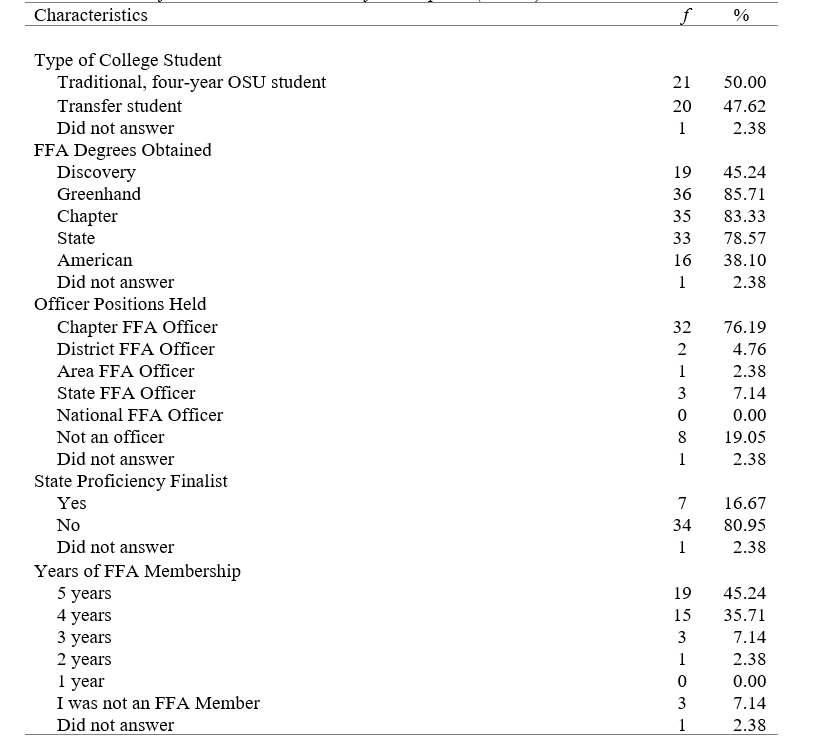

Participants in this study identified as mostly male (f = 30, 93.75%). Three participants (9.38%) indicated they were freshman, nine (28.12%) sophomores, 10 (31.25%) juniors, and 10 (31.25%) seniors. For objective one, design 2: participants indicated positive perceptions of their self-efficacy and agreed they were interested in precision measurement on the pretest; mean scores on their knowledge pretest were 43.75 (SD = 30.3) (see Table 2). As required by design 2, paired-samples t-tests were conducted to detect significant differences between the control group’s pretest and posttest scores. A Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for Type I error with significance of 0.0125 established a priori. Results from t-tests indicated there were no significant differences in perceived self-efficacy [t(15) = 1.40, p = .182] or interest [t(15) = 2.19, p = .045]. There was a significant increase in knowledge scores [t(15) = -3.58, p = .003, d = -.89].

Table 2

Precision Measurement Pretest and Posttest Construct Scores for Design 2

| Pretest (n = 16) | Posttest (n = 16) | ||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-Efficacy | 5.38 | 0.96 | 5.03 | 0.85 | |

| Interest | 4.22 | 0.51 | 3.90 | 0.63 | |

| Knowledge | 43.75 | 30.30 | 77.50 | 21.76 | |

For design 12, pretest scores from the control group were compared to posttest scores from the treatment group for self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge pertaining to precision measurement. As summarized in Table 3, posttest scores indicated treatment participants had positive perceptions of their self-efficacy and somewhat agreed they were interested in the topic. Mean posttest knowledge scores were 81.25 (SD = 19.96). To test for significance in differences between control pretest and treatment posttest scores, a one-way MANOVA was conducted. The omnibus test indicated a significant difference between groups for one or more dependent variables [Wilkes’ Λ = 0.27, p <.001, n2 = .733]. Univariate ANOVAs indicated significantly lower scores for the posttest group on interest [F(1,30) = 11.31, p = .002, n2 = .274] and significantly higher knowledge scores for the posttest group [F(1,30) = 17.09, p <.001, n2 = .363]. No significant differences were found for self-efficacy [F(1,30) = 0.22, p = .641, n2 = .007].

Table 3

Precision Measurement Pretest and Posttest Construct Scores for Design 12

| Pretest (n = 16) | Posttest (n = 16) | ||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-Efficacy | 5.38 | 0.96 | 5.22 | 0.96 | |

| Interest | 4.22 | 0.51 | 3.41 | 0.81 | |

| Knowledge | 43.75 | 30.30 | 81.25 | 19.96 | |

For objective two, pretest measures for design 2 of the carburetor topic indicated participants had positive perceptions of their self-efficacy and agreed they were interested in the topic. Mean pretest knowledge scores were 66.26 (SD = 34.03) (Table 4). Results from paired-sample t-tests indicated no significant differences in perceived self-efficacy [t(15) = 0.83, p = .42], interest [t(15) = 2.53, p = .02], or knowledge [t(15) = -1.62, p = .13] between pretest and posttest scores.

Table 4

Carburetor Pretest and Posttest Construct Scores for Design 2

| Pretest (n = 16) | Posttest (n = 16) | ||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-Efficacy | 5.44 | 0.90 | 5.21 | 0.97 | |

| Interest | 4.34 | 0.51 | 4.07 | 0.48 | |

| Knowledge | 66.25 | 20.66 | 80.00 | 20.66 | |

For design 12, pretest scores from the control group were compared to posttest scores from the treatment group for self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge pertaining to carburetors. Posttest scores indicated participants had positive perceptions of their self-efficacy and somewhat agreed they were interested in the topic. Mean posttest knowledge scores were 80.00 (SD = 20.66) (see Table 5). The one-way MANOVA resulted in an omnibus test indicating a significant difference between one or more dependent variables [Wilkes’ Λ = 0.689, p = .014, n2 = .311]. Subsequent univariate ANOVAs indicated significantly lower scores for the treatment group on self-efficacy [F(1,30) = 4.52, p = .042, n2 = .131] and interest [F(1,30) = 7.27, p = .011, n2 = .195] while knowledge scores were not significantly higher [F(1,30) = 1.91, p = .177, n2 = .060].

Table 5

Carburetor Pretest and Posttest Construct Scores for Design 12

| Pretest (n = 16) | Posttest (n = 16) | ||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Self-Efficacy | 5.44 | 0.90 | 4.69 | 1.08 | |

| Interest | 4.34 | 0.51 | 3.77 | 0.17 | |

| Knowledge | 66.25 | 20.66 | 80.00 | 20.66 | |

Conclusions/Discussion/Implications/Recommendations

Based on the results of this study, we found the precision measurement instructional treatment resulted in a significant increase in knowledge scores for both groups and slight decreases in self-efficacy and interest for both groups. The only significant decrease in interest was observed with Design 12. Possible reasons for the increase in knowledge can be the use of a laboratory experience, having high levels of perceived self-efficacy prior to instruction, and incorporation of all three components of the SLT (Bailey et al., 2017; Bell et al., 2013; Green et al., 2018; Pate et al., 2004). Although it was beyond the scope of this study to determine why there was a decrease in self-efficacy and interest, a decrease is possible according to the literature and is not always associated with knowledge gain (Guo et al., 2020; Hackett & Campbell, 1987; Nuutila et al., 2021). If the topic of precision measurement was more difficult than students expected or they encountered failure with activities and evaluation, decreases in self-efficacy and interest could result (Niemivirta & Tapola, 2008). Based on pretest scores, students had little knowledge of precision measurement prior to instruction, indicating they may have overestimated their ability in the subject.

Similar results emerged for the carburetor topic. For students in both groups there were increases in knowledge, though not significant, and decreases in measured perceived self-efficacy and interest. The decreases in self-efficacy and interest were significant for students in Design 12. Possible causes for decreased self-efficacy and interest discussed for precision measurement could explain decreases for the carburetor topic as well. In the case of knowledge, pretest knowledge was higher than that of precision measurement and may explain why a significant increase was not found. With only 16 students participating in each design group, this study also may not have had the statistical power to detect a difference. The instructional treatment for carburetors included two one-hour class lectures related to the topic, while precision measurement did not. The extra time spent on the topic may have caused the decrease in self-efficacy and interest, because with more time, students can decide they are not interested in the topic and discover their self-efficacy was not as high as previously thought, although this was not a variable measured in this study.

With the internal replication of Designs 2 and 12, one might expect similar results if the study were valid and reliable. While the direction of changes in self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge were the same across both designs and with both topics, significance was not always the same across both designs. A limitation of this study was the small number of students in each group and could contribute to differences among the groups. The research team also acknowledges the low reliability of the knowledge scale; thus, readers should use caution when interpreting results.

Both instructors at the post-secondary level and secondary SBAE teachers could use methods described in this study to teach precision measurement and carburetor part identification and function if their goal is to increase knowledge of these topics. We recommend instructional designers keep in mind the three components of SLT when developing lessons. We also recommend the use of self-recorded videos to evaluate student performance as it provided the benefits previously described (Arikan & Bakla, 2011; Borg & Al-Busaidi, 2012). Relatedly, further research should be conducted to measure the impact videos have on perceived self-efficacy, interest, and knowledge gain. Identifying ways to maintain or increase both self-efficacy and interest while gaining knowledge would also be helpful for those wanting to teach topics related to small engines. To better understand how much time should be spent on specific instructional topics, future studies could measure interest over time so declines in interest can be detected. Another important question to address may be how much interest is enough for learning to occur? Additional testing of instructional designs using SLT in agricultural mechanics and other agriculture topics is also encouraged.

References

Anderson, K., Anderson, R., & Swafford, M. (2022). Effects of a professional development workshop on career and technical education teachers’ perceptions of teaching two-stroke engine repair skills: A preliminary study. Journal of Agricultural Systems, Technology, and Management, 33(1), 1-13. https://jastm.org/index.php/jastm/article/view/10217

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Arikan, A., & Bakla, A. (2011). Learner autonomy online: Stories from a blogging experience. In D. Gardner (Ed.), Fostering autonomy in language learning (pp. 240-251). Zirve University. http://ilac2010.zirve.edu.tr/Fostering_Autonomy.pdf

Atkinson, J. W. (1957). Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychological Review, 64(6), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0043445

Bailey, J. M., Lombardi, D., Cordova, J. R., & Sinatra, G. M. (2017). Meeting students halfway: Increasing self-efficacy and promoting knowledge change in astronomy. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 13(2), 020140. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.13.020140

Bell, R. L., Maeng, J. L., & Binns, I. C. (2013). Learning in context: Technology integration in a teacher preparation program informed by situated learning theory. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(3), 348-379. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21075

Blackburn, J. J., & Robinson, J. S. (2017). An investigation of factors that influence the hypothesis generation ability of students in school-based agricultural education programs when troubleshooting small gasoline engines. Journal of Agricultural Education, 58(2), 50-66. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2017.02050

Blackburn, J. J., Robinson, J. S., & Lamm, A. J. (2014). How cognitive style and problem complexity affect preservice agricultural education teachers’ abilities to solve problems in agricultural mechanics. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(4), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2014.04133

Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Learner autonomy: English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. London: British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng /files/b459%20ELTRP%20Report%20Busaidi_final.pdf

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Houghton Mifflin.

Clark, T. K., Anderson, R., & Paulsen, T. H. (2021). Agricultural mechanics preparation: How much do school based agricultural education teachers receive? Journal of Agricultural Education, 62(1), 17-28. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2021.01017

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Subjective Task Value and the Eccles et al. Model of Achievement-Related Choices. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 105–121). Guilford Publications.

Gable, R. K., & Roberts, A. D. (1983). An instrument to measure attitude toward school subjects. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 43(1), 289-293. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448304300139

Green, C., Eady, M. J., & Andersen, P. J. (2018). Preparing quality teachers: Bridging the gap between tertiary experiences and classroom realities. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 6(1), 104-125. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.6.1.10

Gregg, C., & Bowling, A. (2023). Undergraduate student perceptions of cooperative discussion groups as a classroom engagement tool. NACTA Journal, 67(1), 139-145. https://doi.org/10.56103/nactaj.v67i1.92

Guo, Y. M., Klein, B. D., & Ro, Y. K. (2020). On the effects of student interest, self-efficacy, and perceptions of the instructor on flow, satisfaction, and learning outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 45(7), 1413-1430. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1593348

Hackett, G., & Campbell, N. K. (1987). Task self-efficacy and task interest as a function of performance on a gender-neutral task. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 30(2), 203-215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90019-4

Hainline, M. S., & Wells, T. (2019). Identifying the agricultural mechanics knowledge and skills needed by Iowa school-based agricultural education teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(1), 59-79. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.01059

LaVergne, D. D., Bakhtavoryan, R., & Williams, R. L. (2018). Using a logistic regression approach to estimate the influence of demographical factors on small engine and welding competencies of secondary agricultural education teachers. The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 31(1), 1-11. https://txjanr.agintexas.org/index.php/txjanr/article/view/355

Mathew, S., Bright, K., Barrero-Molina, L. B., & Hawkins, J. (2022, April). Expectancy-value theory. OSU motivation in classrooms lab-motivation minute. https://education.okstate.edu/site-files/documents/motivation-classrooms/motivation-minute-expectancy-value-theory.pdf

National Research Council. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. National Academies Press.

Newcomb, L. H., McCracken, J. D., Warmbrod, J. R., & Whittington, M. S. (2004). Methods of teaching agriculture (3rd ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

Niemivirta, M., & Tapola, A. (2008). Self-efficacy, interest, and task performance: Within-task changes, mutual relationships, and predictive effects. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 21(3/4), 241-250. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.21.3.241

Nuutila, K., Tapola, A., Tuominen, H., Molnár, G., & Niemivirta, M. (2021). Mutual relationships between the levels of and changes in interest, self-efficacy, and perceived difficulty during task engagement. Learning and Individual Differences, 92, 102090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102090

Paek, I. (2015). An investigation of the impact of guessing on coefficient α and reliability. Applied Psychological Measurement, 39(4), 264-277. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621614559516

Pate, M. L., & Miller, G. (2011). A descriptive interpretive analysis of students’ oral verbalization during the use of think-aloud pair problem solving while troubleshooting. Journal of Agricultural Education, 52(1), 107-119. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2011.01107

Pate, M. L., Wardlow, G. W., & Johnson, D. M. (2004). Effects of thinking aloud pair problem solving on the troubleshooting performance of undergraduate agriculture students in a power technology course. Journal of Agricultural Education, 45(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2004.04001

Peake, J. B., Duncan, D. W., & Ricketts, J. C. (2007). Identifying technical content training needs of Georgia agriculture teachers. Journal of Career and Technical Education, 23(1), 44-54. https://journalcte.org/articles/10.21061/jcte.v23i1.442

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33-40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33

Rasty, J., & Anderson, R. G. (2005). The importance of agricultural mechanics skills training: Implications for agricultural education. Journal of Agricultural Systems, Technology & Management, 36(1), 1-13. https://jastm.org/index.php/jastm/article/view/11453

Rosenshine, B., & Furst, N. (1971). Research on teacher performance criteria. In B.O. Smith (Ed.), Research in teacher education: A symposium (pp. 37-72). Prentice-Hall.

Shoulders, C.W., Stripling, C.T., & Estepp, C.M. (2013). Preservice agriculture teachers’ perceptions of teaching assistants: Implications for teacher education. Journal of Agricultural Education, 54(2), 85-98. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2013.02085

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48, 1273-1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2

Talbert, B. A., Croom, B., LaRose, S. E., Vaughn, R., & Lee, J. S. (2022). Foundations of agricultural education (4th ed.). Purdue University Press.

Valdetero, H. E., Kirk, K. R., Dobbins, T. R., & Fravel, P. M. (2015, July 26-29). Teaching small engine diagnostics using mobile app technology. [Paper presentation]. ASABE Annual International Meeting, New Orleans, LA, United States. https://elibrary.asabe.org/pdfviewer.asp?param1=s:/8y9u8/q8qu/tq9q/5tv/L/3471IGHL/HLIHPGGKG.5tv¶m2=J/IK/IGIL¶m3=HJG.HOK.ILI.K¶m4=46279

Wells, T., & Hainline, M. S. (2021). Examining teachers’ agricultural mechanics professional development needs: A national study. Journal of Agricultural Education, 62(2), 217-238. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2021.02217

Wigfield, A. (1994). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation: A developmental perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 6(1), 49-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23359359

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68-81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015 Wigfield, A., Muenks, K., Eccles, J. S., (2021). Achievement motivation: What we know and where we are going. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 3(1), 87-111. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-050720-103500