Emma Cannon Mulvaney, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, emulvaney@beef.org

Joy Morgan, NC State University, jemorga2@ncsu.edu

Wendy Warner, NC State University, wjwarner@ncsu.edu

Travis Park, NC State University, tdpark@ncsu.edu

PDF Available

Abstract

While most developing countries rely on agriculture for survival, many youths lack interest in learning about agriculture or pursuing agricultural careers. Furthermore, the educational system within developing countries often lacks a relevant agricultural curriculum that encourages an interest in learning about agricultural practices or future careers. While numerous studies have investigated how and why educational policy reforms are not effective on large scales through a countrywide adoption of new curriculum, this study sheds light on how an international non-governmental organization (INGO) can have a locally-relevant impact with a small-scale curriculum adoption and implementation process through the lens of Rogan and Grayson’s (2003) Framework for Curriculum Implementation in Developing Countries. Through qualitatively interviewing eight teachers from Uganda who adopted and implemented an INGO agricultural-focused curriculum, the following themes emerged: shift from theoretical to practical applications, motivations of teachers, barriers, curriculum meets students’ needs, survival, curriculum adoption and changed teaching habits, and shift from negative to positive perceptions of agriculture. It is recommended that further research be conducted to understand if students are more likely to become interested in agricultural careers after being taught using a curriculum focused on critical thinking, project-based learning (PBL), and hands-on approaches. It is also recommended that Field of Hope seek continued partnership with Uganda’s Ministry of Education to explore a country-wide adoption of the curriculum.

Introduction

With a growing population estimated to reach 10 billion by the year 2050, food production is of utmost importance and a growing concern for leaders around the world (Mukembo, 2017). In Uganda, 56% of the population is under 18 years of age and 78% of the entire population is below the age of 30 (Ahaibwe et al., 2013); however, the average age of a Ugandan farmer is 54 years old (Lunghabo, 2016). Knowing the population is growing exponentially and understanding that the average age of a farmer outpaces the median age in Sub-Saharan Africa undermines a positive economic outlook relative to the lack of interest in agriculturally-related careers by youths (Mukembo et al., 2014).

“Obtaining a quality education is the foundation to improving people’s lives and sustainable development” (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2017, para. 1). However, in Uganda, the sole emphasis of education is placed on students passing a final examination (Thurmond et al., 2018) rather than providing students with practical knowledge and skills that would support careers, life applications, and self-sustainability upon leaving school (Basaza et al., 2010; Lugemwa, 2014; Mukembo, 2017). Because rural youths are disinterested in agriculture, this is of special concern regarding agricultural education (Bennell, 2007). Additionally, “support for capacity development for youth indirectly productive agricultural activities (especially skills training at all levels) still receives limited support” (Bennell, 2007, p. 4). ActionAid International Uganda, Development Research and Training, and Uganda National NGO Forum (2012) reported that 61.6% of Ugandan youths were unemployed and did not receive skills in school that are necessary to prepare them for the real world.

Even though developing countries often spend 15% to 35% of their national budget on education, educational systems in these countries is inadequate in most instances (Oliveira & Farrell, 1993) due to limited access to knowledge and information (International Movement for Catholic Agricultural and Rural Youth, International Fund for Agricultural Development, & FAO, 2012). In addition, the agricultural education curriculum in developing countries is often outdated, inadequate, and lacks relevance to a rural context (FAO, 2009). Further, agricultural activities are common practices for punishment in many parts of the world, leading to negative attitudes that affect the aspirations toward agricultural careers (MIJARC et al., 2012). However, agriculture, when appropriately integrated into school curricula using practical activities such as school gardens, can encourage youths to pursue agricultural careers (MIJARC et al., 2012).

While educational reform has been attempted in many developing countries by implementing new curricula (O’Sullivan, 2002; Rogan & Aldous, 2005; Serbessa, 2006; Tabulawa, 1998), these curricula are often mandated by policymakers and the implementation process is often neglected. Outdated curricula leave teachers unprepared to adopt and implement the new pedagogies (Hennessey et al., 2010; Rogan & Aldous, 2005) and lacking the content knowledge needed to accompany curriculum. However, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) are more locally- and contextually-relevant to schools in developing countries than governments. They often assist in educational development because of their success in the implementing curriculum and learner-centered teaching methods (Raval al., 2010; Rose, 2009). Field of Hope, an American-based international NGO, has a strong partnership in Uganda working primarily with agriculture teachers, women’s’ groups, and small-scale farmers to “develop agricultural knowledge and enthusiasm among youth and smallholder farmers to sustain nutritionally food secure and economically empowered communities” (Field of Hope Organization, n.d.a., para. 1). After establishing relationships and working with teachers in Uganda, Field of Hope discovered agriculture teachers face many barriers to gathering technical content and information to develop lessons to teach (A. M. Major, personal communication, April 2, 2018). Working together, Field of Hope and Vivayic, a company that designs learning solutions, created a model of how to equip rural Ugandan youth with practical agricultural skills and build their interest in agricultural careers. The two organizations collaborated with Ugandan agriculture teachers to design, write, and pilot a year-long Senior 1 (S1) agricultural education curriculum incorporating content found within the national-level school exams as well as competencies needed to enter an agricultural career or become a small-scale farmer.

Review of Literature

The diversity of schools in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is quite broad across the multiple countries in the region. In well-populated areas, schools can resemble skyscrapers with magnificent educational programs that would rank highly on a global scale. In rural areas, however, schools can lack electricity, running water, doors or windows, or even books (Rogan & Grayson, 2003). In developing countries, children living in poor, rural villages are four times less likely to be in school than a child raised in a wealthy household (United Nations, 2015). Less than one-third of secondary school-aged children are enrolled in schools in SSA (UNICEF, 2012). In 40% of SSA countries, sixth-grade students reach more than 20% of the desired mastery level for reading literacy, but Ugandan sixth-grade students only reach 10% of desired mastery levels (UNESCO, 2007). World Bank Group (2007) reported that rural education needs the most improvement, but vocational training in education can provide technical skills that are useful in agriculture and help alleviate poverty.

In addition, teachers are important in the overall development of any nation (Fareo, 2013); however, teachers in developing countries have neither the experience nor the expectation of collaborating with peers (Rogan & Grayson, 2003) and may even shy away from collaboration for fear of exposing their weaknesses in teaching skills. The small number of teachers in schools is a challenge in SSA where there is a pupil-to-teacher ratio of 40:1 (UNESCO, 2007). Due to the lack of resources in rural areas, schools employ fewer qualified and experienced teachers and experience higher turnover and vacancy rates than in urban schools (UNESCO, 2007). Currently, 1.2 million students are enrolled in secondary schools in Uganda while there are only 20,000 secondary school teachers, yielding a pupil-to-teacher ratio of 60:1 (NCDC, 2019). Only 81% of secondary school teachers in Uganda meet the requirements to teach secondary school, which are the same requirements as primary school (UNESCO, 2007).

Because many Ugandan classrooms are large and teachers use lectures as the primary teaching method, students miss the opportunity to encounter everyday challenges and real-life scenarios, which is the purpose of education (Whitehead, 1929; Mukembo, 2017).The project-based learning (PBL) approach helps students develop interpersonal communication skills, leadership skills, and problem-solving skills in real-life situations and promotes higher-order thinking skills (Mills & Treagust, 2003). Therefore, introducing PBL in agricultural education through entrepreneurial situations could be an option for teachers to initiate agriculture as a viable employment opportunity for students (Mukembo et al., 2014, 2015) and attract more young people to further their education in agriculture (Mukembo, 2017). However, the use of PBL is foreign to most educators in developing countries (Thurmond et al., 2018). Ugandan education is primarily based on the theory and teaching that is classroom-centered (Basaza et al., 2010; Mukembo, 2017; Thurmond et al., 2018). The school garden or farm is rarely used as a learning environment and, in the current model of education, is often used to punish student misbehavior (Mukembo 2017; Thurmond et al., 2018).

The purpose of the secondary school curriculum created by Vivayic and Field of Hope was to create an S1–S4 Ugandan agricultural curriculum that enhances competency in problem-solving and critical thinking skills (Thurmond et al., 2018). Because the curriculum promotes critical thinking skills, it is of high interest to the ministries of education in Uganda and the National Curriculum Development Center in Uganda. In developing countries, NGOs commonly provide schools with resources. Understanding why and how teachers use those resources to adapt and innovate to change leads to a deeper need of exploring their motivations.

Theoretical Framework

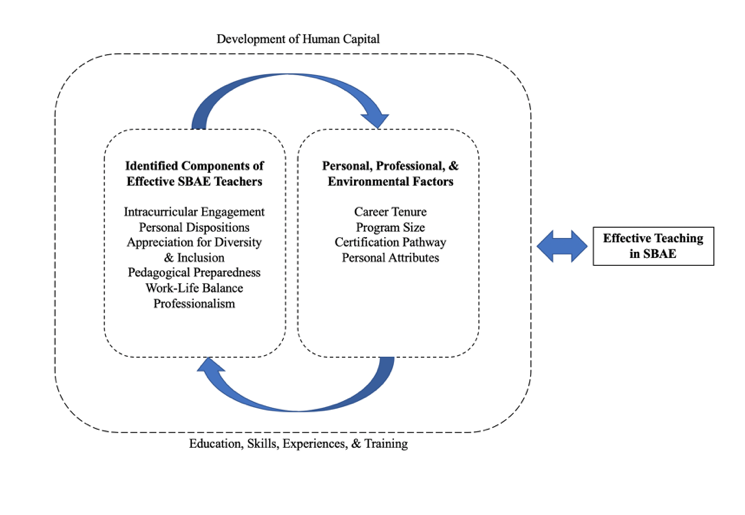

In order to explore how secondary school teachers who partnered with Field of Hope have implemented the new curriculum, a framework developed by Rogan and Grayson (2003) was used focusing on three main constructs: (1) profile of implementation, (2) capacity to support innovation, and (3) support from outside agencies. Profile of implementation refers to the process of employing a new curriculum is not an all-or-nothing proposition and may include segmented stages for implementation (Rogan & Grayson, 2003). The beginning level, orientation and preparation, addresses the time when teachers and faculty “become aware of and prepare to implement the new curriculum” (Rogan & Grayson, 2003, p. 1181). The next levels refer to the mechanical and routine use where the curriculum can be used with minimal modification to the local context (Rogan & Grayson, 2003). The last stages, refinement, integration, and renewal, represent the teacher’s ownership of the curriculum while possibly enriching it with modifications (Rogan & Grayson, 2003).

The capacity to support innovation includes factors supporting or hindering the implementation of new ideas and practices in the new curriculum and recognizes that schools differ in terms of their capacity to implement innovation (Rogan & Grayson, 2003). There are four indicators for the capacity to support innovation: “1) physical resources, 2) teacher factors, 3) student factors, and 4) school ecology and management” (Rogan & Grayson, 2003, p. 186).

The final construct, support from outside agencies, focuses on factors encouraging or limiting support of the implementation of new ideas and practices within the given curriculum (Altinyelken, 2010). Outside agencies are referred to as any organization that is not within the school but helps facilitate innovation by interacting with the school (Rogan & Grayson, 2003). In developing countries, most often the support from outside agencies comes from American agencies and other developed countries that are providing aid (Rogan & Grayson, 2003).

Guiding Questions

The purpose of this basic qualitative study was to explore and derive meaning from the experiences of the instructors teaching agricultural education in Ugandan secondary schools who partnered with Field of Hope and were given a new Senior One (S1) agricultural education curriculum to implement. While this was a part of a larger thesis study, the two specific questions guiding this research were:

- What influences impacted teacher adoption of the curriculum?

- What barriers prevented teachers from adopting the curriculum?

Methodology

Qualitative inquiry was selected as the best method to understand the shared experiences of the teachers delivering a new curriculum provided by Field of Hope within the secondary schools located in northern Uganda. To understand the validity of the interview protocol (Merriam, 2009), a pilot study was completed in North Carolina with two current agriculture teachers who have adopted and implemented a new sustainable agricultural education curriculum. Upon completing the interviews with the participants, the researcher consulted their committee chair regarding the needed alteration of the interview protocol and wording of the questions to fit the needs of the intended data collection (Merriam, 2009).

To “learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry” (Patton, 2002, p. 230), the researcher chose a purposive sample of interviewees. Typical purposeful sampling was used to determine the sample of participants of the basic qualitative study to obtain rich information to study in-depth (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Merriam, 2009; Patton, 2002). This type of sampling was selected because it “reflects the average person, situation, or instance of phenomenon” (Merriam, 2009, p. 78) and contributes to a better understanding of the research problem and the central phenomenon of the study (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 159). To conduct a criterion-based selection of interviewees, the researcher created a list of the essential attributes that included: the teacher taught the S1 curriculum provided by Field of Hope and the teacher attended the teacher training offered by Field of Hope in June 2018. This selection criterion aligned with the purpose of the study to explore and derive meaning from experiences of instructors who were teaching the new S1 agricultural education curriculum and allowed for reflection on the theoretical framework focused on implementation, the capacity to support innovation, and support from outside agencies. A key informant employed by Field of Hope provided the researcher with a document containing the teachers’ information regarding their attendance at the training (Gilchrist, 1992; Rogers, 2003). From the key informant, the researcher was able to identify eight teachers meeting the selection criteria identified for the study. With all eight consenting, the researcher conducted one-on-one, semi-structured interviews to “attempt to understand the world from the subjects’ point of view, to unfold the meaning of their experience, and to uncover their lived world” (Brinkmann & Klave, 2015, p. 3). The interviews were guided by 25 open-ended questions developed by the researcher and three faculty of North Carolina State University. The faculty all had experience in qualitative research, professional development, instructional strategies, international development, and curriculum development. Interviews lasted 30 minutes to one hour and were conducted during the Train the Trainer professional development held by Field of Hope for teachers using the new curriculum.

Before conducting an interview, the researcher shared that she, like each participant, was also was a teacher in a very rural village in Africa. Sharing this information was part of a deliberate effort to create a conversation that would allow the participant to feel somewhat connected to the researcher and to build rapport with her. In addition, the researcher took on the characteristic of neutrality to allow the participant to feel comfortable with the interviewer by refraining from letting her personal views about the subject be known (Merriam, 2009). The interview protocol included six types of interview questions to encourage an array of responses and was created using United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s Framework for Curriculum Implementation in Developing Countries (2017) constructs and sub-constructs and the objectives of the study. The interviews were audio recorded and the researcher took notes during the interviews to capture any reactions, thoughts, or importance of participants’ responses (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Merriam, 2009). The researcher conducted unstructured natural-setting observations and utilized reflexivity to triangulate findings emerging from the interviews (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Merriam, 2009; Tracy, 2010). Observations were collected during visits to schools, meetings with school administrators, and professional development sessions provided to the teachers. Field notes were kept during interviews and observations, and a written reflexive journal was recorded each night to capture important memories, conversations, and interactions of the day (Angen, 2000; Creswell & Poth, 2018; Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Merriam, 2009).

Once all interviews were complete, observations were conducted, and field notes were taken, the researcher utilized the three methods of data management as set forth by Reid (1992): (1) data preparation, (2) data identification, and (3) data manipulation. The researcher compiled the audio recordings of participant interviews and utilized a transcription service to receive an editable document of the recorded interview. The researcher then listened to the audio recordings while reading the transcribed interviews and edited or corrected them to have a verbatim transcription for analyzing data. To begin the data evaluation process, the researcher read each transcript and made memos, and noted key concepts that stood out “to build a sense of the data without getting caught up in the details of coding” (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 198).

During the first-round coding, the researcher utilized in vivo coding to “honor the voices of the participants and their perspectives” (Saldaña, 2013, p. 61). To conduct second-round coding, the researcher utilized axial coding methods to reorganize data coded in the first coding cycle to create a categorical, thematic, and conceptual organization of the data (Saldaña, 2013). Axial coding organized repeating patterns that exemplified potential themes across the data (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). To ensure the observations of the researcher were considered, note-taking and memoing were conducted while coding to create a reflection on the data as a whole (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015; Yin, 2016). Theoretical schemes were constructed from axial codes that exemplified the “significance of interpretations and conclusions in relation to the literature and previous studies” (Yin, 2016, p. 199). To ensure the themes were “describing, classifying, and interpreting the data” (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 189) the themes were analyzed by the researcher.

The three lenses through which the research employed strategies for validating the qualitative study were the: (1) researcher’s lens, (2) participant’s lens, and (3) reader’s or reviewer’s lens (Creswell & Poth, 2018). The researcher employed triangulation and engaged in reflexivity through the researcher’s lens. Through the participant’s lens, member-checking ensured validity and established credibility. Participants were asked to examine rough drafts of the ongoing data analysis process to provide “alternative language, observations, and interpretations” (Stake, 1995, p. 115). Finally, through the reader’s or reviewer’s lens, the researcher employed rich and thick descriptions to corroborate validity. Finally, while collecting interviews, the researcher listened to the recorded interviews at night and confirmed quotes and attitudes with the participants to check for accuracy the next day. Additionally, after the concluding the findings of the study, the researcher traveled back to Uganda and met with participants to discuss findings and ensure accuracy and credibility. This step was crucial to provide credibility because participants were from a different cultural background than that of the researcher. Additionally, English, the language in which interviews were conducted, may not have been the participant’s native language. Member-checking ensured the credibility of the researcher’s preliminary analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Researcher’s Reflexivity

Tracy (2010) defined self-reflexivity as a cognizant awareness of the researcher’s own bias as well as the audience of the researcher. “Self-reflexivity encourages writers to be frank about their strengths and shortcomings” (p. 842). The researcher’s social position was a young adult, white female, American citizen who had worked, volunteered, and traveled both domestically and internationally with agricultural organizations, mostly non-profit organizations. Upon graduating with a baccalaureate degree, the researcher lived in rural Ghana and worked as a Form 1 integrated science and social studies teacher, 4-H advisor, and Extension agent.

From this experience, the researcher was left with a desire to understand why a nation that relies so heavily on agriculture and whose young students know agriculture struggled to teach agriculture. Because of the in-depth experience living and working in rural Sub-Saharan Africa, the researcher utilized bracketing to “mitigate the potential deleterious effects of unacknowledged preconceptions related to the research and thereby to increase the rigor” (Tufford & Newman, 2012, p. 81). In order to set aside personal experiences, “take a fresh perspective toward the phenomenon under examination” (Creswell & Poth, 2018, p. 78), and approach data collection and analyzation, the researcher took on a transcendental approach, meaning “everything is perceived freshly, as if for the first time” (Moustakas, 1994, p. 34).

Findings

Two primary themes emerged for the two research objectives: the shift from theoretical to practical applications and barriers. Within the shift from theoretical to practical applications theme, the following sub-themes emerged: practical applications, allows students to think critically, inclusivity of all learning types, teacher-centered to learner-centered, assessment, and community engagement. In the barriers theme, lack of resources, additional training needed, support from the school, and support from outside agencies emerged as the subthemes.

Research Question One: What influences impacted teacher adoption of the curriculum?

Theme 1: Shift from theoretical to practical applications. Historically, students come to school, sit at their desks, listen to a teacher’s lecture, and watch as they write on the chalkboard. Participants explained this type of learning is theoretical, teacher-centered, and provides students with very little practical application to the subject. The new curriculum provides three class periods of agricultural instruction each week, which is the same as when using the Ugandan curriculum (Ministry of Education and Sports, 2008); however, the new curriculum calls for two of those three days to be spent in the class and one day is “practical,” where the students gain real-world application by visiting the closest environment (farms, gardens, community) that matches what they have learned in class that week.

Practical applications. All eight participants expressed that the new curriculum allowed students to be more involved in the learning through different aspects of practical teaching methods. Grace shared that PBL allows her students to apply situations to the real world: “It’s also you have to do it, let’s make a student think about their home or about the thing and to know what is happening in the surrounding.” Tuno shared that his students complete a beekeeping project where they learn to see how a similar enterprise would operate in the real world. Tuno stated his students appreciated and understood the industry better through practical application, “I came to realize that without, without doing the practical aspects of agriculture learners may not take it more seriously, but when you demonstrate to them and show to them that the things, things that done this way, they learn better than when you tell them in class.”

Allows Students to Think Critically. Participants recognized their role in critical thinking and that their students were thinking in a new manner due to their new behaviors. It was found that students were asking more questions in class than previously, meaning they were considering what to do or believe based on the information presented to them. When asked what skills students were learning, Dowda said, “Critical thinking through writing and their project and, of course, demonstrating in the garden.” Dakar further emphasized her thoughts on critical thinking, “They have to think so that they can . . . always gives them a lot of stress but at the end of the day they learn from their own experiences and that is why I like it so much.”

Inclusivity of All Learning Types. Because of the PBL aspect of the curriculum, many participants agreed that the new methods of teaching were much more beneficial to students at all learning levels. Participants made statements regarding their excitement of students participating that typically did not engage when using the Ugandan curriculum. When using the new curriculum, participants were able to recognize different types of learners had different learning needs, but collectively inclusivity could take place. Kofi shared his beliefs: “The curriculum is able to cater to all students . . . so students that learn on different levels can all learn together from this curriculum.” By recognizing that there were different types of learners, participants were better able to understand their audience and how to address problems their students were facing. Not only did the curriculum allow connections with all students, but the curriculum encouraged teachers to further recognize and identify who needs more specialized assistance.

Teacher-Centered to Learner-Centered. Prior to the new curriculum, participants agreed that the old curriculum was “teacher-centered.” When asked what teacher-centered meant, Isha said: “Whereby you give everything fully then we could also have possibly some small groups.” Through discussing with teachers their thoughts on using the curriculum, five out of the eight participants agreed that they previously used teacher-centered methods and now use a curriculum that is “learner-centered.” Isha also described learner-centered:

Learner-centered simply means most of the things or most of the activities are done by the students themselves. As they do it, they learn it and then they master it. The teacher is just to guide them on what to do.

Participants expressed their excitement for the new curriculum because it reduced their workload, and students seemed to have more control over the learning.

Assessment. Through observations and interviews, the researcher was able to understand that some students were being assessed beyond tests, examinations, and written answers. Rauf showed the researcher his teaching laboratory and explained that he took weeds out of a field and placed them on a lab table for students to identify and explained the growth stages of the plant. In addition, his students dissected a hen for the poultry curriculum. These along with many other observations support participants’ statements that allowed the researcher to understand the practical nature of the curriculum was still reflected in assessments. While Rauf used practical measures to assess students’ learning, the majority of participants used exams, projects, and discussions. Tuno explained he uses “home assignment” as a form of assessment by stating, “Each of the agriculture students . . . they would manage it, and we see now the costs and benefits at the end of the day . . . that would motivate them to do, to do agriculture better.”

Community Engagement. Communal living, working, and sharing of most parts of life is how most Ugandans live. Whether as orphans at a children’s home or in villages of multiple families, Ugandans live and work alongside their extended family members and neighbors. Participants expressed a sense of increased engagement with the surrounding communities as a result of using the curriculum by taking their students into nearby communities to observe, learn from, and see the practical application from farmers in their fields of the lessons they were learning in class. Grace explained how she has adapted to using PBL and critical thinking in her classroom while connecting students’ learning to the real world in a community:

This activity that they can tell you that you have to make a student to do it or you have to go in a community and then you make a student too to see that thing practicality or to do it using the hand, which you can make a student not to forget about that topic.

Participants also expressed students have an increased excitement for going into the communities to learn from their environments so they can easily apply and replicate what they have learned. Using such practical application through the new curriculum has also heightened teachers’ sense of their role in not only a child’s future, but the future of the communities the children come from because so many communities rely on the practical aspects of agriculture to feed their families. Dakar expressed this by saying, “It has made me to know the benefit of the application. It also made me, reminded me about my role in the community.” Dakar explained how, through implementing the curriculum, teachers have been able to involve the farmers in the community to use the practical nature of the curriculum: “Field of Hope has trained me how to associate with the community by putting a demonstration farm because if I put a demonstration farm, many people will now come and be asking questions on what to do. So, it has already given me how to reach the community.”

Research Question Two: What barriers prevented teachers from adopting the curriculum?

Theme 2: Barriers. While Field of Hope provided participants and their agricultural programs a new curriculum, there were still barriers that participants faced that hindered their complete and full adoption of the curriculum with many being out of the control of the participants.

Lack of Resources. The majority of the S1 curriculum contains practical lessons focused on how to grow plants in a garden setting. All eight participants expressed the need for additional resources and materials to fully implement the curriculum and incorporate critical thinking and PBL into their classrooms. While six of the eight schools reported having a garden, they reported lacking the necessary tools or equipment to work effectively in the garden. Dakar explained the consequences of teaching without the proper resources:

The only challenge we have is that in Uganda, or in some schools in Uganda we lack some of the apparatus for practicals and it make most of the teachers now to teach agriculture what? Theoretically which it doesn’t become meaningful. But agriculture needed to be taught what? Practical.

Equipment is necessary to run any kind of agricultural operation. Kofi had 96 students in S1 which presented a challenge with only a few watering cans for during the dry season which ultimately impacted the school garden. Fred shared, “As teachers we try to improvise or be creative enough, but the actual physical resources are not many except land, land we have.”

Additional Training Needed. During interviews, participants expressed appreciation to Field of Hope for supporting, empowering, and following up by visiting schools. Teachers desired further training on a multitude of subjects to better implement the practical nature of the curriculum and increase their knowledge to deliver the curriculum to the best of their abilities. While Uganda has a diverse agriculture industry, participants reported the need for more locally relevant examples in the curriculum. Rauf described his desire to learn more about crops produced in the region in which he teaches in Uganda:

Some of the crops that they’ll put in the curriculum, which may not be in our region, how to grow them . . . Like uh, we have never grown apples in our country here . . . They grow coffee in Uganda, just maybe not in this region.

In addition, some teachers desired to be trained further on using the curriculum to incorporate more PBL and critical thinking. Fred shared his desire to learn about teaching methods: “So, I realized the teaching method should always be practical, scientific, practical for the learning to be more to the learners even to you as a teacher.” Teachers also recognized the need for training that would recruit other teachers to use the curriculum and provide opportunities to highlight Ugandan agriculture.

Support from School. In Uganda, there are a variety of schools including government-funded schools, private schools, and boarding schools, all with varying levels of support for the new curriculum. Fred described having support from his school director but also said that his school “fails to provide what I needed for the lesson or for the curriculum. Being the first time I’m introducing the curriculum, they’re not seriously in support, but I hope with time.” A few of the teachers also had difficulty convincing administration to allow them to use the new curriculum. Rauf explained how he convinced his school leadership to allow him to use the curriculum provided by Field of Hope: “They thought it was something separate, but now when it’s explained. It is, it is incorporated in the syllabus of Uganda and then . . . I brought the curriculum and tried to go with the syllabus and compare to it.”

While most teachers who were interviewed reported the lack of school support, there were a few who shared their positive experiences about the support their school gives. Grace, who teaches at a children’s home, also reported having positive experiences regarding support of the school leadership:

“They love when students are going for practicals or PBL or when they are working in the school garden they encourage, the buy the produce that is the student always produced and it’s made it, the students make me to know that, that they are encouraging the curriculum that we have to push on with it.”

Support from Outside Agencies. One of the three pillars of the Framework for Curriculum Implementation in Developing Countries is support from outside agencies. Participants were asked if they received support from any other NGOs or private donors to assess the support from outside agencies. Six of the participants reported that they do not receive support from any other agency besides Field of Hope. When asked if their schools received any funds from donors Dakar responded, “Not yet,” and Rauf said, “We have not yet received.” Fred and his headmaster gave the researchers a tour of the school and explained their relationship with Notre Dame University. Through this relationship, the school has received enough solar panels to provide the entire campus with electricity and Wi-Fi, which only uses approximately one-half of the electrical supply.

Conclusions

From the analysis of interviews with eight teachers, two themes and multiple subthemes emerged in gaining an understanding of the influences and barriers to adopting a new agricultural curriculum. Theme 1, the shift from theoretical to practical applications, concluded that the practical application provided by the new curriculum allows students to experience learning in an entirely new way rather than through teaching that was theoretically or lecture-based. Supporting research by Chiasson (2008) and Mukembo (2017), the subtheme practical applications highlighted how the new curriculum with practical application allowed students to comprehend what they are learning, construct questions to further their understanding (think critically), and then go home over the holidays to repeat what they have learned with family or friends. In addition, participants now have the ability to recognize the different levels of learners, creating a more inclusive environment (inclusivity of all learning types). The new curriculum provides diversity in learning through varied instructional styles, which aids in student understanding because participants realized not all students learn best from lectures. The learners are able to take control of their knowledge (learner-centered) by applying themselves to the subject through hands-on work during practical days. The teachers are not only using practical methods of teaching but are also using practical methods of assessing students (assessment) allowing them to continue to reinforce real-world applications. Through using the curriculum, teachers have become increasingly connected to community members and have been reminded of their role in building the future citizens of the communities from which these children come (community engagement). Teachers encourage students to go into their communities and test out their new knowledge learned on their families’ or neighbors’ farms.

Teachers have been supported by Field of Hope through the curriculum and training they received; however, they still face barriers (theme 2) that prevent them from being able to fully use the curriculum in the way it is intended. Teachers struggle to provide practical applications to their students due to a large number of students, lack of land for gardens, and tools (lack of resources). This conclusion is critical to the success of implementing the curriculum because the FAO (2004) argues that school gardens are encouraged in developing countries as experiential learning tools to improve the quality of education. The participants were thrilled at the practical aspects of the curriculum, but additional training is needed relevant to teaching skills and agricultural knowledge to increase their understanding and confidence in delivering information to their students and incorporating more PBL and critical thinking. This conclusion is supported by Hennessey et al. (2010), who argued that the technical expertise of the teacher is critical for any new implementation to take place. The level of support from the school varied among the participants, but the major lack of support related to the funds available to purchase needed supplies related to the instruction supports the research by Rogan and Grayson (2003). The main source of support from outside agencies in the study is the INGO Field of Hope, however, several of the schools received support from other agencies which increased the support for the students and the activities. This curriculum implementation and support received from Field of Hope were unique from other studies completed using the Framework for Curriculum Implementation in Developing Countries because there was a constant connection to a supporting agency with ongoing support versus curriculum being distributed and teachers learning to adapt.

Recommendations and Implications

To fully understand the needs of agricultural education in developing countries and curriculum implementation, more research is needed. Using Roger’s (2003) Diffusion of Innovations, a study on the transfer of new agricultural knowledge during the holidays would allow teachers to see if their efforts are leading to family and community adoption of agricultural practices (Okikoret al., 2011). Research should also be conducted to follow students who complete S1 through S4 using the Field of Hope curriculum to further understand the impact curriculum is having on students. A capacity instrument should be administered both before and after students are taught the curriculum that contains themes of technical aspects of agriculture, agriculture careers, soft skills, and overall attitudes toward agriculture to measure changes in capacity. To further understand the impact that teacher training and professional development sessions are having on participants, a formal evaluation of training should be conducted to determine the effectiveness and to improve planning.

In addition, more can be done to impact curricular success. To ensure teachers implementing curricula understand PBL and critical thinking, it is recommended that a formal process for training teachers be developed and acquire local Ugandan trainers who would enable sustainability and potentially elongate the training process. The administrations of schools adopting and implementing curriculum should be involved to ensure full awareness of the NGO’s intentions, involvements, and teacher professional development goals as this could spur additional support.

References

ActionAid International Uganda, Development Research and Training, & Uganda National NGO Forum. (2012). Lost opportunity? Gaps in youth policy and programming in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: https://uganda.actionaid.org/sites/uganda/files/youthrepot-final_0.pdf

Ahaibwe, G., Mbowa, S., & Lwanga, M. M. (2013, June). Youth engagement in agriculture in Uganda: Challenges and prospects. Environmental Policy Research Center (No. 106). https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/159673/2/series106.pdf

Altinyelken, H. (2010). Curriculum change in Uganda: Teacher perspectives on the new thematic curriculum. International Journal of Educational Development, 30,151–161.

Angen, M. J. (2000). Evaluating interpretive inquiry: Reviewing the validity debate and opening the dialogue. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230001000308

Basaza, G. N., Milman, N, B., & Wright, C. R. (2010). The challenges of implementing distance education in Uganda: A case study. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 11(2). https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/irrodl/1900-v1-n1-irrodl05138/1067689ar.pdf

Bennell, P. (2007). Promoting livelihood opportunities for rural youth. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development. https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/40257372/youth_engagement.pdf/ba904804-060c-49ed-83c5-bd5d70a99335

Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S. (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). Sage.

Chiasson, P. (2008). Peirce’s design for thinking: A philosophical gift for children. In M. Taylor, Creswell, J. & Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among the five approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. & Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among the five approaches (4th ed). Sage.

Field of Hope Organization. (n.d.a). Mission – About us. https://fieldofhope.org/content/mission.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2004). School gardens concept note: Improving child nutrition and education through the promotion of school garden programs. [Government publication]. http://www.fao.org/3/af080e/af080e00.htm.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2009). Education for rural people. [Government publication]. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0760e.pdf.

Food and Agriculture Organization. (2017). Sustainable development goals: Sustainable Development Goal 4 ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. [Government Publication]. http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/goals/goal-4/en/.

Hennessey, S., Harrison, D., & Wamakote, L. (2010). Teacher factors influencing classroom use of ICT in Sub-Saharan Africa. Itupale Online Journal of African Studies, 2, 39–54. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228399541_Teacher_factors_influencing_classroom_use_of_ICT_in_Sub-Saharan_Africa.

International Movement for Catholic Agricultural and Rural Youth, International Fund for Agricultural Development, & Food and Agriculture Organization. (2012). Summary of the findings of the project implemented by MIJARC in collaboration with FAO and IFAD: ‘Facilitating access of rural youth to agricultural activities.’ https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/Facilitating+access+of+rural+youth+to+agricultural+activities.pdf/325bda30-ac08-494f-a37d-3201780a5dff.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage.

Lugemwa, P. (2014). Improving the secondary school curriculum to nurture entrepreneurial competencies among students in Uganda. International Journal of Secondary Education, 2(4), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijsedu.20140204.13

Lunghabo, J. W. (2016), January 6). How we can make farming gainful. Daily Monitor. http://www.monitor.co.ug/Magazines/Farming/How-we-can-make-farming-gainful/689860-3021952-7klmmt/index.html.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

MIJARC, FAO, & IFAD (2012). Summary of the findings of the project implemented by MIJARC in collaboration with IFAD and FAO: Facilitating access of rural youth to agricultural activities. https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/Facilitating+access+of+rural+youth+to+agricultural+activities.pdf/325bda30-ac08-494f-a37d-3201780a5dff

Mills, J. E., & Treagust, D. F. (2003). Engineering education – Is problem-based or project-based learning the answer? Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 3(2), 2–16. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/246069451_Engineering_Education_Is_Problem-Based_or_Project-Based_Learning_the_Answer

Ministry of Education and Sports. (2008). Agriculture teaching syllabus. Kampala, Uganda: National Curriculum Development Center.

Mukembo, S. C. (2017). Equipping youth with agripreneurship and other valuable skills by linking secondary agricultural education to communities for improved livelihoods: A comparative analysis of project-based learning in Uganda (Doctoral dissertation). https://shareok.org/handle/11244/299532.

Mukembo, S. C., Edwards, M. C., Ramsey, J. W., & Henneberry, S. R. (2014). Attracting youth to agriculture: The career interests of young farmer club members in Uganda. Journal of Agricultural Education, 55(5),155–172. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2015.03016

National Curriculum Development Center. (2019). Report of the stakeholders’ feedback workshop on agricultural education, agri-food systems and youth employment in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: Ministry of Education and Sports Printing Office.

Okikor, J. J., Oonyu, J., Matsiko, F., & Kibwika, P. (2011). Can schools offer solutions to small-scale farmers in Africa? Analysis of the socioeconomic benefits of primary school agriculture in Uganda. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 17(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2011.544454

Oliveira, J., & Farrell, J. (1993). Teachers in developing countries: Improving effectiveness & managing costs [EDI seminar series file copy]. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/877441468764687308/pdf/multi-page.pdf.

O’Sullivan, M. (2002). Reform implementation and the realities within which teachers work: A Namibian case study. A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 32, 219–237. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03057920220143192.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Raval, H., Mckenney, S., & Pieters, J. (2010). A conceptual model for supporting para-teacher learning in an Indian non-governmental organization (NGO). Studies in Continuing Education, 32, 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.515571

Reid, A. O., Jr. (1992). Doing qualitative research, Vol. 3. Sage.

Rogan, J., & Aldous, C. (2005). Relationships between the constructs of a theory of curriculum implementation. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42, 313-336.

Rogan, J., & Grayson, D. (2003). Towards a theory of curriculum implementation with particular reference to science education in developing countries. International Journal of Science Education, 25, 1171–1204.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Rose, P. (2009). NGO provision of basic education: Alternative or complementary service delivery to support access to the excluded? Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 39 (2), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920902750475

Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Sage.

Serbessa, D. (2006). Tension between traditional and modern teaching-learning approaches in Ethiopian primary schools. Journal of International Cooperation in Education, 9, 123–140. https://home.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/cice/wp-content/uploads/publications/Journal9-1/9-1-10.pdf.

Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

Tabulawa, R. (1998). Teachers’ perspectives on classroom practice in Botswana: Implications for pedagogical change. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11, 249–268. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ605807.

Thurmond, W., Denney, A., & Kueker, D. (2018). Vivayic & Field of Hope: Designing project-based learning agricultural curriculum for secondary Ugandan classrooms. Paper presented at the AIAEE Conference Celebrating the Intersection of Human, Natural, and Cultural Systems. https://www.aiaee.org/attachments/category/181/AIAEE_Proceedings_2018.pdf.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. (2017). Developing and implementing curriculum frameworks. [Training Tools for Curriculum Development.] https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000250052

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. (2007). EFA Global Monitoring Report. [Strong Foundations, Early Childhood Care and Education.] http://www.unesco.org/education/GMR/2007/Full_report.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2012). Progress for children: A report card on adolescents (UNICEF Publication No. 10). https://www.unicef.org/media/files/PFC2012_A_report_card_on_adolescents.pdf

United Nations. (2015). The Millennium Development Goals report. [Data file]. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). The aims of education and other essays. The Macmillan Company.

World Bank Group. (2007). World development report 2008: Agriculture for development. Washington D.C.: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/5990/WDR%202008%20-%20English.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y Yin, R. K. (2016). Qualitative research from start to finish (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press