D. Barry Croom, University of Georgia, dbcroom@uga.edu

Ashley M. Yopp, Florida Department of Education, ashley.yopp@fldoe.org

Don Edgar, New Mexico State University, dedgar@nmsu.edu

Richie Roberts, Louisiana State University, roberts3@lsu.edu

Carla Jagger, University of Florida, carlajagger@ufl.edu

Chris Clemons, Auburn University, cac0132@auburn.edu

Jason McKibben, Auburn University, jdm0184@auburn.edu

O.P. McCubbins, Mississippi State University, am4942@msstate.edu

Jill Wagner, Mississippi Department of Education, am4942@msstate.edu

Abstract

Determining the professional development needs of teachers framed through the national career pathways of agricultural education has become imperative for modern classrooms. Participants in this study were from six Southeastern U.S. states. Most were female educators, with the largest group having teaching experience between 11-20 years. Participants indicated their professional development needs regarding technical content in the seven agricultural education career pathways. Based on the findings, the researchers concluded that participants needed professional development in plant science, followed closely by animal systems. The least beneficial area for professional development was power, structural and technical systems, and food products and processing systems. No differences existed between male and female teachers regarding their technical professional development needs except within the power, structural, and technical pathway. Teachers with less than 10 years of teaching experience reported a greater need for professional development in animal science than their more experienced counterparts. Finally, participants in rural school systems were more likely to desire professional development on natural resources.

Introduction and Review of Literature

Teachers with a high level of content knowledge are better equipped to help their students succeed academically and can be more effective as educators (National Research Council, 2010). The content knowledge held by teachers has been shown to have a statically significant effect on student learning. When content knowledge is of sufficient depth and quality, the impact on student learning has also been positive (Ambrose et al., 2010). As teachers employ high-quality pedagogical strategies, their content knowledge helps students improve knowledge retention and learning transfer (National Research Council, 2010). In agricultural education, teachers need content knowledge of sufficient depth and breadth to meet the current and future demands of the agricultural industry (Solomonson & Roberts, 2022).

Facilitating Understanding

Teachers with quality content knowledge can help students understand the material more deeply and meaningfully. They can explain concepts clearly, provide relevant examples, and confidently answer questions (Driel, 2021; Gess-Newsome et al., 2019). On this point, Harris and Hofer (2011) found that teachers with more content knowledge were more strategic in selecting learning tasks, created more student-oriented learning activities, and were more deliberate in planning lessons. Pursuing this further, Marzano (2017) proposed that teachers with a high level of content knowledge were more capable of helping students detect errors in their reasoning and successfully solve problems in the real world. Teachers often use content knowledge to guide students to examine how new technical content differs from their existing assumptions. This strategy deepens their understanding of key concepts (Dean & Marzano, 2012; Walshaw, 2012). Ambrose (2010) suggested that content knowledge and intellectual proficiency were key drivers in a teacher’s ability to successfully use technical content to facilitate students’ learning in the classroom.

Adaptability

Adaptability refers to the ability of teachers to modify their teaching strategies to meet the needs of their students. Teachers with content knowledge can be more adaptable in their teaching. They can adjust their teaching strategies and methods to suit the needs of their students and make adjustments when necessary (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2009). Edgar (2012) postulated that the more content knowledge a teacher possesses, the more likely the teacher would employ varying means to teach the content.

Building Credibility

Building credibility as a teacher has become essential to creating a positive and effective learning environment. Teachers with content knowledge are more credible to their students, parents, and colleagues. The rich source of content knowledge that teachers can draw upon in the classroom has become the source of most of this credibility (Forde & McMahon, 2019). They can speak with authority on their subject matter and inspire confidence in their teaching (Bolkan & Goodboy, 2009; Finn et al., 2009).

Effective planning

Teachers with content knowledge can also create more effective lesson plans and assessments and deploy more effective teaching strategies (Orlich et al., 2012; Senthamarai, 2018). For example, they can design activities and assessments that accurately measure student learning and identify the essential concepts students need to learn (Hume et al., 2019). Previous research has suggested that teacher preparation programs must focus more on understanding how teachers acquire technical content knowledge and support their ability to communicate such to their students (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Levine, 2008). For this study, technical knowledge referred to the lesson elements designed to provide students with instruction, practice, and review of information regarding the agricultural sciences.

Agricultural Education Teacher Professional Development Systems

Agricultural education teachers who were traditionally certified often receive technical content training during their initial teacher preparation phase. Formal teacher preparation traditionally begins during college coursework (Croom, 2009). During this period, the preservice teachers are inducted into teaching through training and development (Talbert et al., 2022). However, concerns arise about the ability of novice teachers to deliver content-rich lessons (Roberts et al., 2020a, 2020b). Induction follows the competency-building stage, where technical content skill development continues. This phase is where most professional and skill development occurs (Croom, 2009; Fessler & Christensen, 1992).

Professional development usually involves teachers attending professional development sessions based on their perceived technical content deficiencies (Smalley et al., 2019) because teachers sense their need to address technical content deficiencies through continuous professional development (Easterly & Myers, 2019). Despite this desire to develop technical skills, previous research has found a significant gap in agricultural mechanics skill development and other technical agriculture concepts (Easterly & Myers, 2019; Yopp et al., 2020).

Conceptual Framework

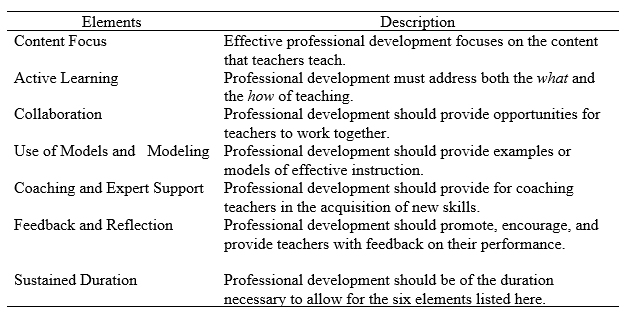

Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) proposed that teacher professional development proceeds through seven elements (see Table 1). Effective professional development employs strategies that deepen a teacher’s technical content knowledge. However, this is not enough. Teachers also need sustained professional development activities of sufficient duration that demonstrate how to teach technical content. Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) further proposed that teachers were best served by professional development provided in a social environment, with teachers collaborating and exploring effective instructional models under expert coaches’ guidance. Teachers needed to reflect on their performance to internalize new content knowledge and the strategies for teaching it (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). This model for professional development begins with developing technical content knowledge (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). The research team focused on this element of the model because we contended that professional development was grounded in content skill development applied through effective teaching strategies.

Table 1

Elements of Effective Professional Development adapted from Darling-Hammond et al. (2017)

The connection between professional development in the content taught is that both are needed to support effective teaching practices. Teachers who have a strong understanding of the content they are teaching and who have the skills and knowledge needed to teach that content effectively will be better equipped to meet the needs of their students and support their learning (Ambrose et al., 2010; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Additionally, ongoing professional development and content training can help teachers stay up-to-date with the latest research-based practices, teaching strategies, and techniques, which can further improve their teaching practices over time (Darling-Hammond et al., 2002).

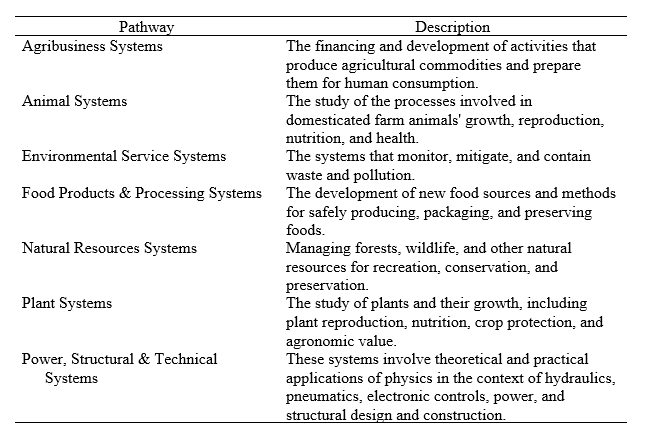

The agricultural education curriculum covers a range of grade levels and a wide range of technical content. It provides students with knowledge as the content transitions from more basic to advanced skill development through pathway progression. As a result, secondary agricultural education teachers must provide essential knowledge and experiences through advanced instruction in animal science, agricultural engineering, plant and soil science, forestry, natural resources, food processing, and agricultural business management (Talbert et al., 2022). Therefore, secondary students must have the skills to navigate complex problems regarding agriculture, food, and natural resources using good reasoning skills (Figland et al., 2020). Table 2 illustrates the seven areas of agricultural sciences as identified by Advance CTE (2018) and describes the primary learning attribute guiding the learning activities.

Table 2

Agriculture, Food & Natural Resources Career Pathways adapted from Advance CTE (2021)

Purpose and Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the professional development needs of teachers in the Southeast United States regarding the national career pathways for secondary agricultural education. After describing the demographics of teachers who participated in the study, the objectives were to:

- Determine the professional development needs of teachers in the Southeastern region of the United States in each of the seven career pathways described by Advance CTE, and

- Compare the professional development needs of teachers by gender, years of teaching experience, and community setting.

Methods

This descriptive study sought to determine teacher perceptions regarding professional development needs as framed by the seven career pathways in the agricultural education curriculum. We distributed an instrument Yopp et al. (2020) developed to the target population of agricultural science teachers in six Southeastern states. We used each state’s directory of agricultural science teachers provided by state agricultural education authorities to define the target population.

We developed the questionnaire to address each research objective, including demographic questions. We included 54 Likert-scale items based on seven career pathways developed by Advance CTE (2018): Power and Technical Systems (16 items), Plant Systems (8 items), Natural Resources (4 items), Food Products and Processing (7 items), Environmental Service Systems (5 items), Animal Systems (7 items), and Agribusiness Systems (7 items). We asked participants to rate each item based on its perceived benefit level using this scale: 1 = not beneficial to 5 = essential. We entered data into SPSS® version 24.0 to calculate means and standard deviations. We conducted further analysis through t-tests to determine the significance between variables of interest.

A panel of agricultural teachers with expert knowledge of Advance CTE career pathways examined the questionnaire for content and face validity. Using methods proposed by Creswell and Creswell (2017), we pilot-tested the questionnaire with a sample of 14 pre-service agricultural education teachers using the test re-test method. These test measures yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .83 to .91 (.70 or higher acceptable range). Our post-hoc reliability analysis of the instrument yielded an overall valid measure (α = .86).

Guided by Dillman et al. (2014) tailored design method, researchers administered the instrument to prospective participants via email using each state’s unique agricultural education teacher listserv. The research team sent an initial invitation to participate in the study. We followed this with a second message to engage participants through an opt-in email directing them to a Qualtrics hyperlink specific to their respective instrument by state. Lastly, the researchers sent two follow-up reminder emails to non-respondents over four weeks. Previous instrument implementation (Yopp et al., 2020) yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from .83 to .91 (Creswell & Clark, 2017). Post-hoc analysis of the instrument based on the population of interest revealed an overall α = .81.

Due to the nature of school-based agricultural education (SBAE) and participants’ ability to respond in a timely manner, early and late responders were evaluated to determine whether response differences occurred (Lindner et al., 2001). Analysis revealed no differences (p = .45) in the population of interest. The final response rate gained was 52.24 %. We anticipated this because decreased response rates to web-based instruments have been reported, especially in recent decades, with the influx of messaging in professional environments. Baruch (1999) noted that rates have declined from approximately 65% to 48% when using electronic survey methods. On this issue, Fraze et al. (2003) found that SBAE teachers responded less frequently to electronic surveys, possibly due to overloaded work schedules.

Findings

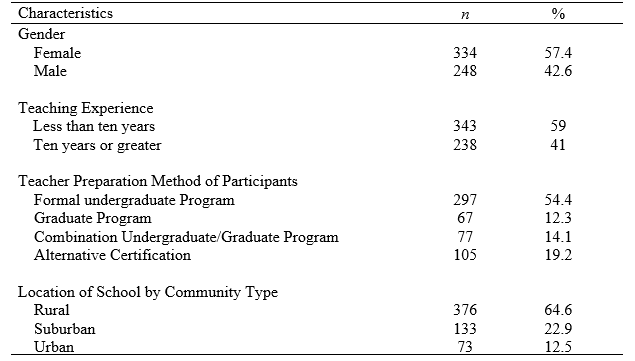

Female participants outnumbered male participants in this study, and most participants were still in their first 10 years of teaching. Most participants received formal training to become teachers through a traditional undergraduate program in agricultural education. Many teachers (n = 107) earned their teacher certification through an alternative certification program. The majority of teachers in this study taught in rural schools. Urban agricultural educators made up the smallest percentage of participants in this study. Table 3 provides a detailed representation of the socio-demographic characteristics of participants.

Table 3

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Participants

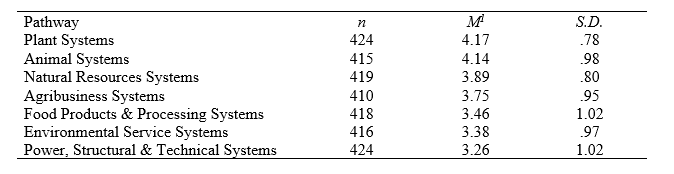

Objective One: Professional Development Needs in the Seven Career Pathways

Based on data gathered from SBAE teachers and guided by the career pathway to frame the professional development needs, we found that the essential area was that of Plant Systems (M = 4.17, S.D. = .78) and closely followed by Animal Systems (M = 4.14, S.D. = .98). The career pathway with the least beneficial area for professional development was Power, Structural & Technical Systems (M = 3.26, S.D. = 1.02) with Food Products & Processing Systems (M = 3.46, S.D. = 1.02) having a similar response by respondents. The two lowest career pathways also displayed the most variation of answers, as identified by participants. Table 4 shows the professional development needs of agriculture teachers based on career pathways in agricultural education.

Table 4

Professional Development Needs of Agriculture Education Teachers Based on Career Pathways

Note. 1 indicates a scale used from 1 = Not beneficial to 5 = Essential with 3 = No opinion

Objective Two: Professional Development Needs of Teachers by Gender, Years of Teaching Experience, and Community Setting.

The research team collected data on the professional development needs of participants aligned with career pathways and disaggregated based on gender. Two pathway areas had statistically significant differences based on gender. We found significant differences between genders within the Power Technology (p = .000) and Natural Resources (p = .005) pathways. The remaining pathways did not reveal significant differences based on gender. Table 5 displays the needs for professional development in career pathways by gender.

Table 5

Needs for Professional Development in Career Pathways based on Gender

Note. 1 indicates a scale used from 1 = Not beneficial to 5 = Essential with 3 = No opinion

The research team gathered data on the professional development needs of participants aligned with career pathways and analyzed it based on years of experience. The Animal Systems pathway has significant differences based on experience (p = .005). Although the means reported were similar (4.14 and 4.13), the associated standard deviations were dissimilar (1.07 and 0.86), resulting in statistically significant differences between the groups regarding experience. The remaining pathways did not have substantial differences based on experience level. Table 6 details participants’ professional development needs based on years of teaching experience.

Table 6

Needs for Professional Development in Career Pathways Based on Experience

Note. 1 indicates a scale used from 1 = Not beneficial to 5 = Essential with 3 = No opinion

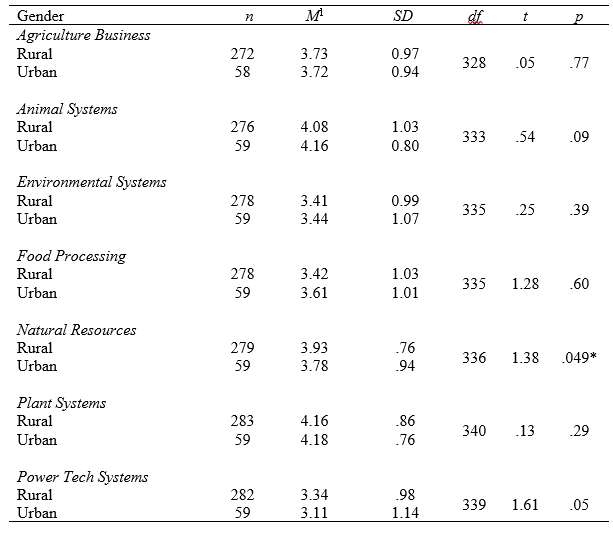

Participants reported their professional development needs regarding career pathways based on the impact of the community setting. The Natural Resources pathway (p =. 049) indicated significant differences based on the community setting. Table 7 displays the needs for professional development based on the community type.

Table 7

Needs for Professional Development in Career Pathways Based on the Community Type

Note. 1 indicates a scale used from 1 = Not beneficial to 5 = Essential with 3 = No opinion

Conclusions & Implications

This study aimed to investigate the professional development needs of teachers in the national career pathways in agricultural education. The divisions of gender and years of experience do not represent a generalizable representation of each state regarding the professional development needs of agriculture teachers. Participants in this study were from six states in the Southeastern United States. Most respondents were female, with the largest group having teaching experience between 11-20 years. Respondents were experienced and prepared mainly for their teaching career through traditional means.

Participants were asked to indicate their professional development needs regarding technical content in the seven career pathways. Based on the findings, we concluded that professional development was most needed in the specialized content area of plant science, followed closely by animal systems. Meanwhile, we also conclude that the least beneficial areas for professional development were Power, Structural & Technical Systems, and Food Products & Processing Systems. Concerning Power, Structural & Technical Systems, the findings are inconsistent with the results of similar studies (Easterly & Myers, 2019; Smalley et al., 2019) that have reported a significant gap in teacher preparation in this area. However, we conclude from our findings that teachers do not perceive technical training in Power, Structural & Technical Systems to be a significant need.

Further conclusions evoked through this research population werethat no differences exist between male and female teachers regarding their technical in-service training needs, with two exceptions. More males than females found the need for training in natural resources and power and technical systems. Further, teachers with less than 10 years of teaching experience need more training in animal science than their more experienced counterparts. This is consistent with the teacher development model developed by Fessler and Christensen (1992). The only significant difference among respondents for this research objective was that rural teachers rated natural resources training higher than their urban counterparts. We found that teachers in rural schools were more likely to require training on natural resources. This could result from rural teachers’ access to more natural resources and, therefore, more opportunities to teach this content area than a teacher in an urban setting.

Recommendations for Future Research

Based on the conclusions from this study, this study should be replicated in other regions of the United States to gain a clearer picture of the professional development needs of agricultural education teachers. Agriculture operations vary across the United States due to climate, arable land, geography, and access to infrastructure that supports markets and transportation. The teachers in one region may have different professional needs from those in another. This study should be replicated in the future to determine if teacher training needs have changed. The agriculture industry uses human ingenuity and innovation to power new and better methods for producing food, fiber, and natural resources. Consequently, agricultural educators must be well-equipped to educate students using innovative technology.

This study found differences between male and female teachers in power, structural and technical systems, and natural resources. Additional research in this area may help determine why these differences exist. Furthermore, we noted differences between new and experienced teachers concerning animal science. This begs the question as to whether Inservice training needs should be customized based upon the years of experience. Researchers should conduct follow-up studies to determine if this would benefit teachers.

References

Advance CTE. (2018). Agriculture, food & natural resources. Agriculture, Food & Natural Resources. https://careertech.org/Agriculture

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., Norman, M. K., & Mayer, R. E. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Baruch, Y. (1999). Response rate in academic studies – A comparative analysis. Human Relations, 52(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679905200401

Bolkan, S., & Goodboy, A. K. (2009). Transformational leadership in the classroom: Fostering student learning, student participation, and teacher credibility. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 36(4), 296–306. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ952280

Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications.

Croom, B. (2009). The effectiveness of teacher education as perceived by beginning teachers in agricultural education. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 59, 1-13. http://jsaer.org/pdf/Vol59/2009-59-001.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L., Chung, R., & Frelow, F. (2002). Variation in teacher preparation: How well do different pathways prepare teachers to teach? Journal of Teacher Education, 53(4), 286–302. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0022487102053004002

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

Dean, C. B., & Marzano, R. J. (2012). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. ASCD

Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J. D., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th edition). Wiley.

Driel, J. V. (2021). Developing science teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004505452_001

Easterly, R. G., & Myers, B. E. (2019). Professional development engagement and career satisfaction of agriscience teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(2), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.02069

Edgar, D. W. (2012). Learning theories and historical events affecting instructional design in education: Recitation literacy towards extraction literacy practices. Sage Open, 2(4), 1–9. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244012462707

Fessler, R., & Christensen, J. C. (1992). The teacher career cycle: Understsnding and guiding the professional development of teachers. Allyn and Bacon.

Figland, W., Roberts, R., & Blackburn, J. J. (2020). Reconceptualizing problem-solving: Applications for the delivery of agricultural education’s comprehensive, three-circle model in the 21st Century. Journal of Southern Agricultural Education Research, 70(1), 1–20. http://jsaer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Volume-70-Full-Issue.pdf#page=35

Finn, A. N., Schrodt, P., Witt, P. L., Elledge, N., Jernberg, K. A., & Larson, L. M. (2009). A meta-analytical review of teacher credibility and its associations with teacher behaviors and student outcomes. Communication Education, 58(4), 516–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903131154

Forde, C., & McMahon, M. (2019). Teacher quality, professional learning and policy: Recognising, rewarding and developing teacher expertise. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53654-9

Fraze, S. D., Hardin, K. K., Brashears, M. T., Haygood, J. L., & Smith, J. H. (2003). The effects of delivery mode upon survey response rate and perceived attitudes of Texas agriscience teachers. Journal of Agricultural Education, 44(2), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2003.01027

Gess-Newsome, J., Taylor, J. A., Carlson, J., Gardner, A. L., Wilson, C. D., & Stuhlsatz, M. A. M. (2019). Teacher pedagogical content knowledge, practice, and student achievement. International Journal of Science Education, 41(7), 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1265158

Harris, J. B., & Hofer, M. J. (2011). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) in Action: A descriptive study of secondary teachers’ curriculum-based, technology-related instructional planning. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(3), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2011.10782570

Hume, A., Cooper, R., & Borowski, A. (Eds.). (2019). Repositioning pedagogical content knowledge in teachers’ knowledge for teaching science. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-5898-2

Levine, S. (2008). School lunch politics: The surprising history of America’s favorite welfare program. Princeton University Press.

Lindner, J. R., Murphy, T. H., & Briers, G. E. (2001). Handling nonresponse in social science research. Journal of Agricultural Education, 42(4), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2001.04043

Marzano, R. J. (2017). The new art and science of teaching. Solution Tree Press.

National Research Council (U.S) (Ed.). (2010). Preparing teachers: Building evidence for sound policy. National Academies Press.

Orlich, D. C., Harder, R. J., Callahan, R. C., Trevisan, M. S., & Brown, A. H. (2012). Teaching strategies: A guide to effective instruction. Cengage Learning.

Roberts, R., Stair, K. S., & Granberry, T. (2020a). Images from the trenches: A visual narrative of the concerns of agricultural education majors. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(2), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.02324

Roberts, R., Wittie, B. M., Stair, K. S., Blackburn, J. J., & Smith, H. E. (2020b). The dimensions of professional development needs for secondary agricultural education teachers across career stages: A multiple case study comparison. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(3), 128–143. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.03128

Senthamarai, S. (2018). Interactive teaching strategies. Journal of Applied and Advanced Research, 3(1), 36–38. https://doi.org/10.21839/jaar.2018.v3iS1.166

Solomonson, J. K., & Roberts, R. (2022). Organizing and administering school-based agricultural education systems and the FFA. In A. C. Thoron & R. K Barrick (Eds.)., Preparing agriculture and agriscience educators for the classroom (pp. 17-34). IGI Global.

Smalley, S., Hainline, M., & Sands, K. (2019). School-based agricultural education teachers’ perceived professional development needs associated with teaching, classroom management, and technical agriculture. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2019.02085

Talbert, B. A., Croom, B., LaRose, S., Vaughn, R., & Lee, J. S. (2022). Foundations of agricultural education (4th ed.). Purdue University Press.

Walshaw, M. (2012). Teacher knowledge as fundamental to effective teaching practice. Math Teacher Education, 15, 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-012-9217-0

Yopp, A., Edgar, D., & Croom, D. B. (2020). Technical in-service needs of agriculture teachers in Georgia by career pathway. Journal of Agricultural Education, 61(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2020.02001